In the realm of modern health and nutrition, few topics generate as much confusion—or as many misconceptions—as the difference between food allergies and food intolerances. These terms are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation, but medically, they describe two fundamentally distinct physiological responses with varying implications for health, diagnosis, and treatment. To describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance accurately requires a nuanced understanding of the immune system, digestive processes, and how each condition manifests in the body. Mislabeling one for the other can lead not only to ineffective dietary adjustments but also to potentially serious health consequences, especially for individuals with true allergies. In this article, we will explore the clinical, biological, and practical distinctions between allergy versus intolerance, offering a detailed, evidence-based guide for consumers and health-conscious readers alike.

You may also like: Macronutrients vs Micronutrients: What the Simple Definition of Macronutrients Reveals About Your Diet and Health

Understanding Food Allergy: A True Immune Reaction

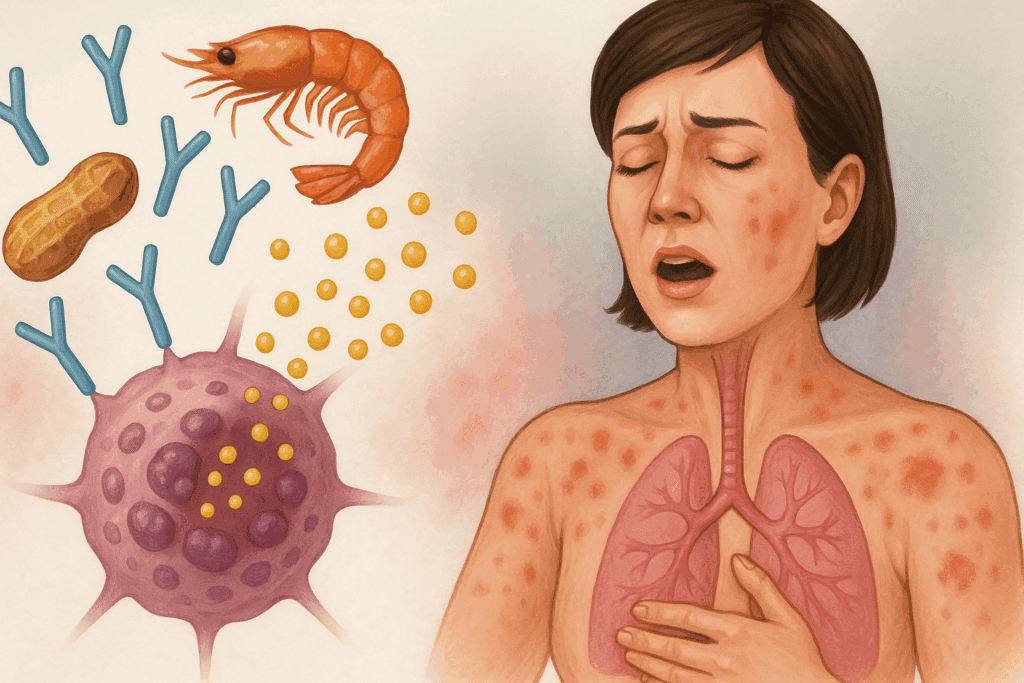

When discussing food allergy, one must begin with the immune system. A food allergy is defined as an abnormal immune response to a specific protein found in a food. This response is typically mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies, which recognize the protein as a harmful invader. Upon exposure, the immune system releases histamine and other chemicals that trigger symptoms ranging from mild skin reactions to life-threatening anaphylaxis. It is important to note that food allergy is not a digestive issue—it is an immune issue, which makes answering the question “is food allergy digestion?” straightforward. No, a food allergy does not originate in digestion, though gastrointestinal symptoms can occur as part of the systemic immune response.

Classic examples of food allergens include peanuts, shellfish, tree nuts, eggs, and milk. Even trace amounts of these allergens can provoke severe reactions in sensitized individuals. Symptoms may include hives, swelling, difficulty breathing, abdominal pain, or cardiovascular collapse in the case of anaphylaxis. Because food allergy can be immediately life-threatening, rapid recognition and management—often with epinephrine—is essential. Diagnosing food allergy typically involves a combination of skin prick tests, blood tests for IgE antibodies, and medically supervised food challenges. It is critical to distinguish this from other reactions, as misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary fear or inadequate protection.

Describing Food Intolerance: A Digestive System Sensitivity

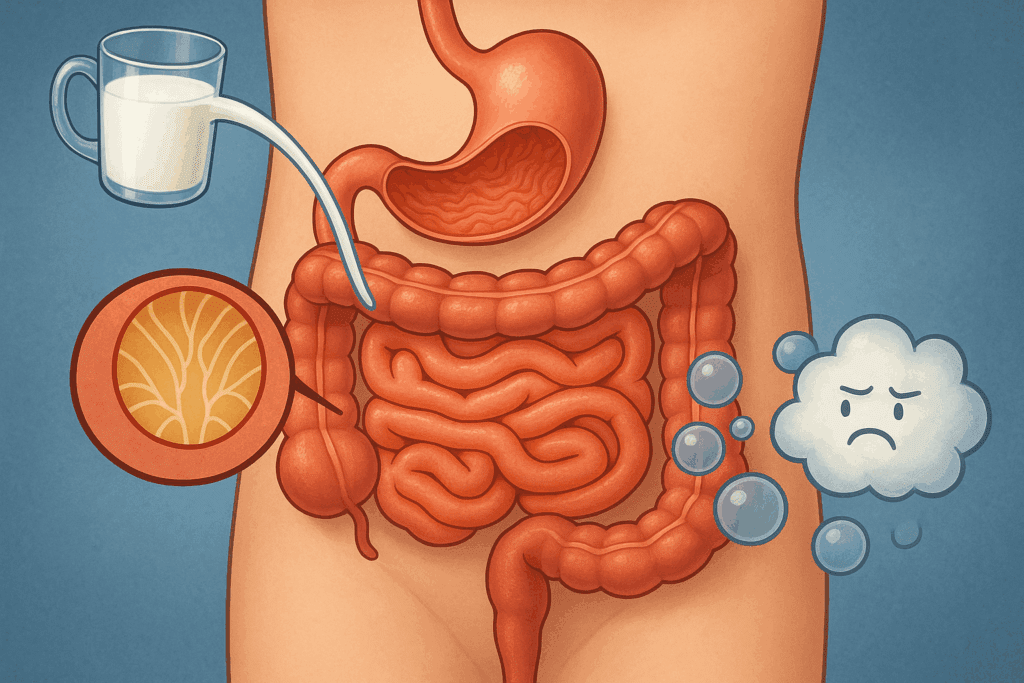

In contrast, food intolerance originates not in the immune system but in the digestive tract. Food intolerance refers to the body’s inability to properly digest or metabolize a particular food or component of food. A commonly cited example is lactose intolerance, where individuals lack sufficient amounts of lactase, the enzyme necessary to digest lactose, the sugar found in milk. When lactose is not broken down in the small intestine, it passes into the colon undigested, leading to gas, bloating, cramps, and diarrhea. Thus, to define food intolerance in a sentence and definition: food intolerance is a non-immune, digestive sensitivity that results from enzyme deficiencies, chemical reactions, or fermentation processes in the gut.

Importantly, food intolerance is generally dose-dependent, meaning symptoms are more likely to appear when a person consumes large quantities of the problematic food. Unlike food allergy, food intolerance does not cause anaphylaxis and is not considered life-threatening. Nevertheless, the discomfort and disruption to daily life that it can cause are significant and warrant proper attention. Diagnosis is usually based on clinical history and elimination diets rather than immunologic testing, and management focuses on identifying and avoiding trigger foods, sometimes with the assistance of digestive aids like lactase supplements.

Comparing Food Intolerance Versus Allergy: Mechanisms and Manifestations

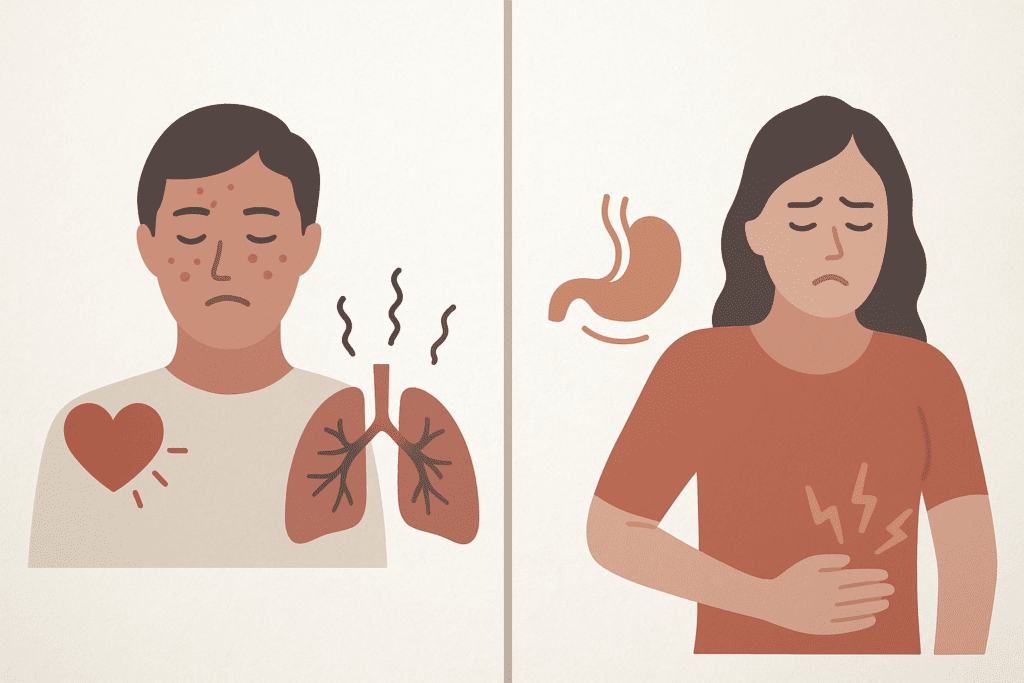

To truly grasp the implications of food intolerance versus allergy, one must consider not only the physiological mechanisms involved but also the timelines and symptom patterns. Food allergies typically provoke rapid onset symptoms—often within minutes to two hours after ingestion—while food intolerances may take several hours or even a full day to cause noticeable discomfort. Furthermore, allergy-related symptoms can affect multiple organ systems, including the skin, respiratory tract, and cardiovascular system. In contrast, food intolerance is more likely to produce symptoms that are limited to the gastrointestinal tract.

The type of medical intervention required also underscores the difference. Allergy management may include life-saving treatments like auto-injectable epinephrine, antihistamines, or corticosteroids. On the other hand, managing food intolerance usually involves diet modifications and possibly enzyme supplementation. From a public health perspective, failing to describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance clearly can result in either unnecessary dietary restrictions or dangerous underestimation of allergy severity.

The Role of Immune Response in Allergy Versus Intolerance

The hallmark of an allergy is its reliance on the immune system, specifically the adaptive immune system’s creation of antibodies that recognize and attack perceived threats. In IgE-mediated food allergies, this immune cascade is swift and potentially severe. There are also non-IgE mediated food allergies, such as eosinophilic esophagitis or food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), which are immune-mediated but do not involve IgE. These can cause chronic gastrointestinal issues, especially in children, further complicating the landscape of diagnosis.

Food intolerance, by contrast, involves no immune system engagement. There are no antibodies created, no inflammatory immune response, and therefore no risk of anaphylaxis. This distinction cannot be overstated, especially in clinical settings where determining whether a reaction is immune-mediated dictates treatment and emergency preparedness. Individuals and parents of children with suspected reactions must understand whether the issue is a food intolerance or allergy, as confusing the two may lead to improper care.

Is Food Allergy Digestion? Clarifying a Common Misconception

One of the most persistent myths in popular health discussions is the belief that a food allergy is simply a form of “bad digestion” or that it can be resolved with probiotics or dietary adjustments alone. However, this assumption fundamentally mischaracterizes what food allergy is. To reiterate, food allergy is not digestion—it is an immune response. It is triggered not by improper breakdown of food in the stomach or intestines but by an inappropriate immune reaction to a protein the body mistakenly sees as dangerous. This reaction can happen regardless of the state of digestion.

The confusion likely arises because both food allergy and intolerance can produce gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain or diarrhea. But the underlying causes—and therefore the treatment approaches—are entirely different. Gastrointestinal symptoms in food allergies are a downstream effect of immune activation, not poor digestion per se. Understanding this difference is essential for choosing the right intervention and communicating clearly with healthcare professionals.

How Food Allergy and Food Intolerance Impact Nutritional Health

Misunderstanding allergy versus intolerance can also have consequences for long-term nutritional health. For example, individuals who mistakenly believe they are allergic to dairy when they are actually lactose intolerant may unnecessarily avoid all dairy products, including those that are naturally low in lactose like hard cheeses or lactose-free milk. This can result in calcium and vitamin D deficiencies, particularly among children, adolescents, and older adults. Conversely, people who mistake a serious allergy for a simple intolerance may inadvertently expose themselves to foods that can cause life-threatening reactions.

Nutritional counseling should always be part of the care plan for anyone with a diagnosed food intolerance or allergy. A registered dietitian can help identify safe food alternatives, ensure nutrient adequacy, and clarify whether an avoidance is medically necessary. In both conditions, the goal is not only symptom control but also overall nutritional balance and quality of life.

Diagnosis and Testing: Navigating the Gray Areas

Diagnosing food intolerance versus allergy can sometimes be challenging, especially because symptoms may overlap or be delayed. For food allergies, diagnostic tools include skin prick testing, serum-specific IgE testing, and oral food challenges performed in medical settings. These tests help identify immune responses that confirm an allergy diagnosis. For intolerances, however, diagnosis often relies on dietary history, food and symptom diaries, and elimination diets. In some cases, breath tests may be used—for example, to diagnose lactose or fructose intolerance.

There is a growing market for at-home food sensitivity tests, which often measure IgG antibodies. However, these tests are controversial and not recommended by most medical organizations because IgG responses are not markers of allergy or intolerance but rather indicators of exposure. Consumers must be cautious when interpreting such results and should always seek guidance from a qualified healthcare professional.

The Psychological and Social Impacts of Misunderstood Food Reactions

Another layer of complexity in distinguishing food intolerance versus allergy is the psychological impact these diagnoses carry. Individuals living with food allergies often experience anxiety about accidental exposure, especially in social settings like restaurants or schools. The fear of anaphylaxis can significantly impair quality of life and requires ongoing vigilance. On the other hand, people with food intolerance may feel dismissed or misunderstood, especially if their symptoms are not considered “serious” by peers or even healthcare providers.

Both conditions carry emotional weight and deserve empathy and evidence-based support. Educational outreach, accurate food labeling, and inclusive dining practices can help reduce the burden and stigma for those managing either type of condition. Understanding the lived experience behind each diagnosis is part of applying the principles of EEAT—Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness—in both clinical practice and public education.

Building Health Literacy: How to Describe the Difference Between a Food Allergy and Food Intolerance

To effectively describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance to the public, educators and healthcare professionals must use language that is both scientifically accurate and accessible. One effective strategy is to use metaphor: a food allergy can be compared to a fire alarm triggered by smoke—an overreaction to something harmless—whereas food intolerance is more like a plumbing problem—something isn’t flowing or breaking down properly.

Using real-life examples also helps reinforce the distinction. For instance, someone with a peanut allergy might experience swelling of the lips and difficulty breathing within minutes of exposure, even if they only touched a food prepared near peanuts. Meanwhile, a person with lactose intolerance might enjoy a small amount of yogurt without issue but feel bloated and gassy after drinking a full glass of milk. These illustrations help contextualize the abstract and often confusing medical terminology in a relatable way.

Real-World Application: Managing Food Allergies and Intolerances in Daily Life

The day-to-day management of food allergies versus food intolerances looks quite different and requires tailored strategies. For those with allergies, strict avoidance, careful label reading, and carrying emergency medication are essential practices. Schools, airlines, and workplaces must implement policies that protect individuals from accidental exposure. For people with food intolerances, the approach may be more flexible, involving threshold testing and use of digestive aids like lactase enzymes or low-FODMAP diets for irritable bowel syndrome.

It is also important to recognize that new food reactions can develop over time, and a diagnosis is not necessarily static. Children may outgrow certain allergies, such as to milk or eggs, while adults may develop new sensitivities or intolerances later in life. Staying in communication with healthcare providers, updating testing as needed, and remaining attentive to symptoms are all part of comprehensive care.

Food Labels and Consumer Awareness: Avoiding Confusion

Food labeling plays a critical role in helping consumers make safe choices, but it also contributes to the confusion between food intolerance versus allergy. The term “may contain” is often used for cross-contamination risks, which are relevant for allergies but less so for intolerances. Products labeled “dairy-free” may still contain casein, a milk protein that could trigger allergies, while being free of lactose, which is the primary concern for intolerance.

Clearer labeling standards, combined with improved public education, can help bridge the gap between what consumers think they’re avoiding and what they are actually ingesting. Food manufacturers, policymakers, and advocacy organizations all have a role to play in ensuring that individuals with both allergies and intolerances can eat safely and confidently.

Frequently Asked Questions: Food Allergy vs. Food Intolerance

1. Can someone have both a food allergy and a food intolerance at the same time?

Yes, it is entirely possible for a person to experience both a food allergy and a food intolerance simultaneously, even to the same food. For example, someone might have a lactose intolerance, which affects digestion, and also have a dairy allergy, which involves the immune system reacting to milk proteins like casein or whey. In such cases, differentiating symptoms becomes complex, making it critical to work closely with an allergist and a gastroenterologist. When trying to describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance in such dual scenarios, professionals rely on diagnostic tools like IgE blood testing and food elimination trials. This layered dynamic underscores the importance of not simplifying the allergy versus intolerance discussion, as both can coexist but require different management strategies.

2. Why do people often confuse food allergies with food intolerances?

The confusion between food intolerance versus allergy often stems from overlapping symptoms such as bloating, nausea, and diarrhea. However, the root causes are different: food intolerance results from digestive difficulties, while allergies stem from immune reactions. Because symptoms may manifest in the gastrointestinal system for both, people sometimes mistakenly assume they are the same. Media portrayal and marketing labels can further blur the lines, especially when “sensitivity” is used vaguely. This is why it’s so important to describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance clearly in both healthcare settings and public communication, using evidence-based explanations that highlight the immune vs. digestive origins.

3. How can stress or mental health influence food intolerance symptoms?

Unlike allergies, food intolerance symptoms can be exacerbated by emotional or psychological stress. The brain-gut connection—mediated through the enteric nervous system—plays a critical role in amplifying symptoms like cramping, bloating, and irregular bowel movements. Someone with lactose or fructose intolerance may find that stressful periods worsen their discomfort, even if their food intake remains unchanged. In this context, using food intolerance in a sentence and definition that accounts for stress could be: “Food intolerance is a non-immune digestive response that can be intensified by emotional stressors.” Understanding these nuances reinforces how food intolerance versus allergy differs not only biologically but also in how lifestyle factors influence symptoms.

4. Are there any food intolerances that might eventually develop into food allergies?

There is currently no solid scientific evidence that food intolerances directly evolve into food allergies. However, chronic exposure to certain food components in individuals with compromised gut integrity (such as in leaky gut syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease) might alter immune tolerance over time. This doesn’t mean that the intolerance causes the allergy, but it might contribute to an environment where the immune system becomes sensitized. It’s important to distinguish this subtle point when discussing allergy versus intolerance so as not to suggest false causality. Clinicians stress the importance of medical monitoring in patients with chronic intolerances, especially if new symptoms such as hives or breathing issues emerge.

5. How do elimination diets help differentiate allergy vs intolerance?

Elimination diets are often used to identify food intolerances because intolerances are dose-dependent and cumulative. Removing a suspected food and then reintroducing it gradually helps isolate the offending item. However, this method is not typically safe or accurate for diagnosing allergies, especially IgE-mediated ones, which can cause severe reactions. For allergies, a medically supervised oral food challenge or lab testing is preferred. This distinction again helps describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance: allergies require immunological testing and often carry life-threatening risk, while intolerances are more about uncovering digestive thresholds and managing symptoms nutritionally.

6. Are food allergies always lifelong conditions, while intolerances are temporary?

While some food allergies are lifelong, others—especially in children—may resolve over time. Common examples include allergies to milk, egg, or wheat, which many children outgrow. In contrast, food intolerances can fluctuate based on digestive health, enzyme levels, and gut microbiota, meaning they can improve or worsen depending on health status. Therefore, the assumption that allergies are always permanent and intolerances are always temporary oversimplifies the allergy vs intolerance discussion. For both conditions, regular reassessment is crucial, as symptoms and tolerances may change over time due to age, hormonal shifts, or medical treatment.

7. Can food intolerances impact nutrient absorption long-term?

Yes, chronic food intolerances—particularly when left unmanaged—can negatively affect nutrient absorption. For example, lactose intolerance may lead individuals to avoid dairy entirely, risking calcium and vitamin D deficiencies. Similarly, fructose intolerance can influence the absorption of other monosaccharides, potentially contributing to broader malabsorption issues. These effects are not commonly seen in food allergies unless the allergy leads to strict dietary avoidance that limits nutrient intake. So when examining food intolerance versus allergy from a nutritional standpoint, intolerances often have broader implications for micronutrient status over time due to digestive enzyme imbalances and gut fermentation processes.

8. How does labeling on packaged food contribute to confusion around allergy versus intolerance?

Food packaging frequently uses vague terms like “dairy-free” or “may contain,” which can mislead consumers into thinking a product is safe for their condition. For example, a product labeled “lactose-free” may still contain milk proteins like casein, posing a danger to someone with a dairy allergy. Conversely, a food labeled “nut-free” might be safe for someone with an allergy but still cause issues in someone with a nut oil intolerance. The failure to describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance in labeling practices creates real-world risks. Regulatory reforms that enforce precise terminology could help reduce misinterpretation and protect consumers with either condition.

9. Is there a link between gut microbiome health and food intolerance symptoms?

Emerging research suggests a strong connection between the composition of the gut microbiome and the severity of food intolerance symptoms. Individuals with imbalanced gut flora may have heightened sensitivity to certain carbohydrates or proteins due to fermentation imbalances. This makes the concept of food intolerance in a sentence and definition even more dynamic: it’s not only a digestive inability but also a microbiome-mediated response. In contrast, the role of the microbiome in allergies is more about immune modulation and barrier integrity. Understanding how allergy versus intolerance interacts with gut health may lead to future interventions involving probiotics or microbiome-targeted therapies.

10. What are the long-term psychological impacts of being misdiagnosed with a food allergy instead of an intolerance (or vice versa)?

Misdiagnosis in the context of food intolerance versus allergy can carry serious psychological effects. A person falsely diagnosed with a food allergy may develop unnecessary anxiety about eating, social events, or restaurant visits, believing their life is at risk with certain foods. Conversely, someone who is told they merely have an intolerance but actually has a life-threatening allergy may experience trauma if exposed unknowingly. Mislabeling conditions also undermines trust in healthcare systems and can lead to disordered eating habits. It’s essential to describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance accurately to avoid these emotional burdens and ensure that individuals receive the proper treatment, dietary guidance, and psychological reassurance.

Conclusion: Why Describing Food Allergy and Intolerance Accurately Matters for Better Health

Understanding how to describe the difference between a food allergy and food intolerance is far more than a semantic exercise—it is a critical step toward improving health outcomes, preventing avoidable medical emergencies, and promoting nutritional well-being. Food intolerance in a sentence and definition reveals it to be a digestive sensitivity, while allergy is rooted in immune dysfunction. Clarifying these terms can empower patients, reduce misdiagnoses, and guide more appropriate treatment plans.

When we accurately differentiate allergy versus intolerance, we move beyond oversimplification and into the realm of personalized care. Whether we are asking, “Is food allergy digestion?” or trying to interpret confusing food labels, the clarity we bring to these concepts can directly shape behavior, health policy, and clinical recommendations. A deeper understanding of food intolerance versus allergy allows for more effective dietary choices, safer environments, and better support for individuals navigating complex food-related conditions.

Further Reading:

What’s the Difference Between a Food Allergy and a Food Intolerance?

Food Allergy vs. Intolerance: What’s the Difference?