Introduction: Why Digestion Is the Cornerstone of Wellness

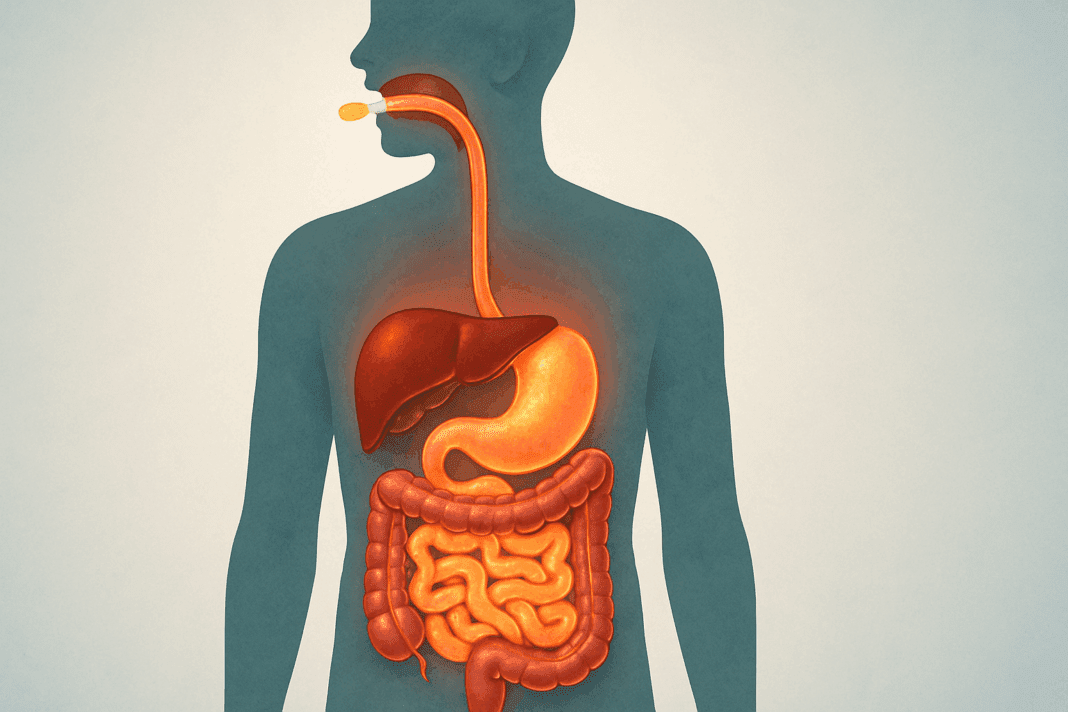

Digestion is far more than a biological function—it is the foundation of health, vitality, and longevity. Every time we eat, the body initiates a complex series of processes designed to convert food into energy, repair tissue, support immunity, and maintain balance across virtually every organ system. Yet, most of us rarely stop to consider how this transformation occurs. To truly grasp the connection between diet and health, we must first understand the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials that power our digestive system. With each bite, a silent but highly coordinated interaction of mechanical force, enzymatic activity, and cellular absorption begins—a dynamic choreography that determines how effectively we extract nutrition from our meals.

You may also like: Macronutrients vs Micronutrients: What the Simple Definition of Macronutrients Reveals About Your Diet and Health

The Dual Mechanisms of Digestion: Physical vs. Chemical Breakdown

At the heart of digestion are two fundamental mechanisms: mechanical (or physical) breakdown and chemical digestion. These processes work in harmony but serve distinct roles. The physical act of chewing, churning, and mixing food helps reduce large food particles into manageable fragments. This physical transformation increases the surface area available for enzymes to act upon, setting the stage for effective nutrient extraction.

Meanwhile, chemical digestion relies on enzymes and acids to break molecular bonds, transforming complex carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into absorbable forms such as glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids. Together, these two processes form the backbone of digestion. Understanding the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials allows us to see how each nutrient pathway is uniquely processed, optimized, and delivered to the body for use.

The Role of the Mouth: Where Digestion Begins

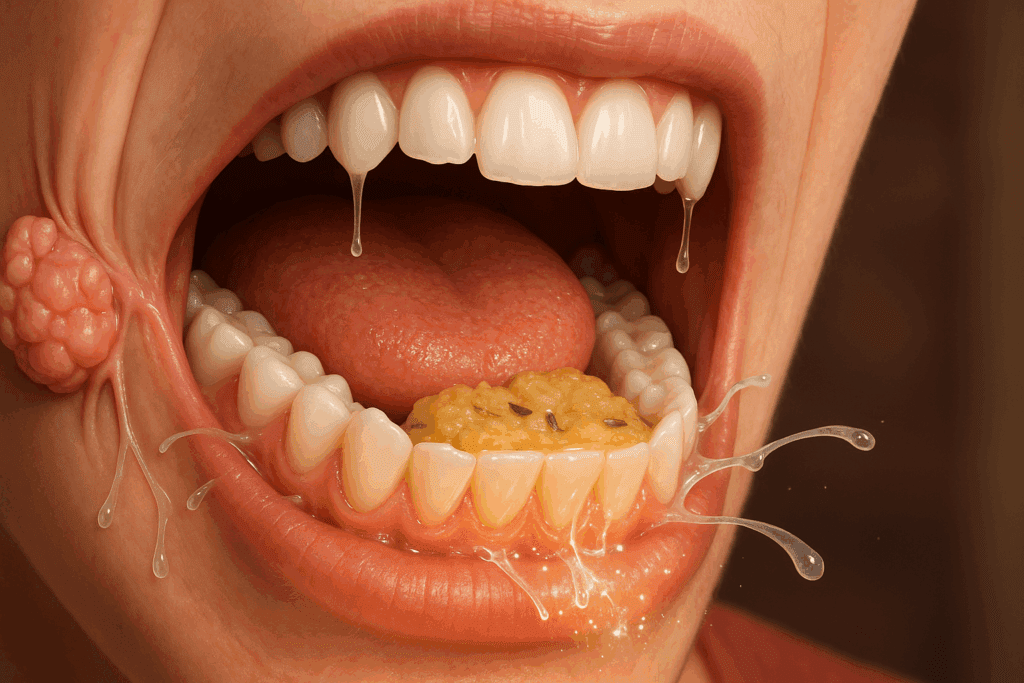

Digestion begins not in the stomach, but in the mouth—the first gateway in the gastrointestinal system. Here, the mechanical act of chewing initiates the breakdown of food. Teeth grind solid particles into smaller pieces, while the tongue helps mix food with saliva. This seemingly simple step is essential because it ensures food is small enough to be efficiently processed further down the digestive tract.

Saliva plays a critical role in chemical digestion. It contains the enzyme amylase, which begins the breakdown of starches into simpler sugars. As such, the mouth is a primary site where both physical and chemical digestion occur simultaneously. For example, even before a slice of bread reaches the stomach, its carbohydrates are already partially digested—demonstrating the importance of this early phase in understanding how the body manages the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials.

Stomach Function: Mechanical Churning Meets Chemical Action

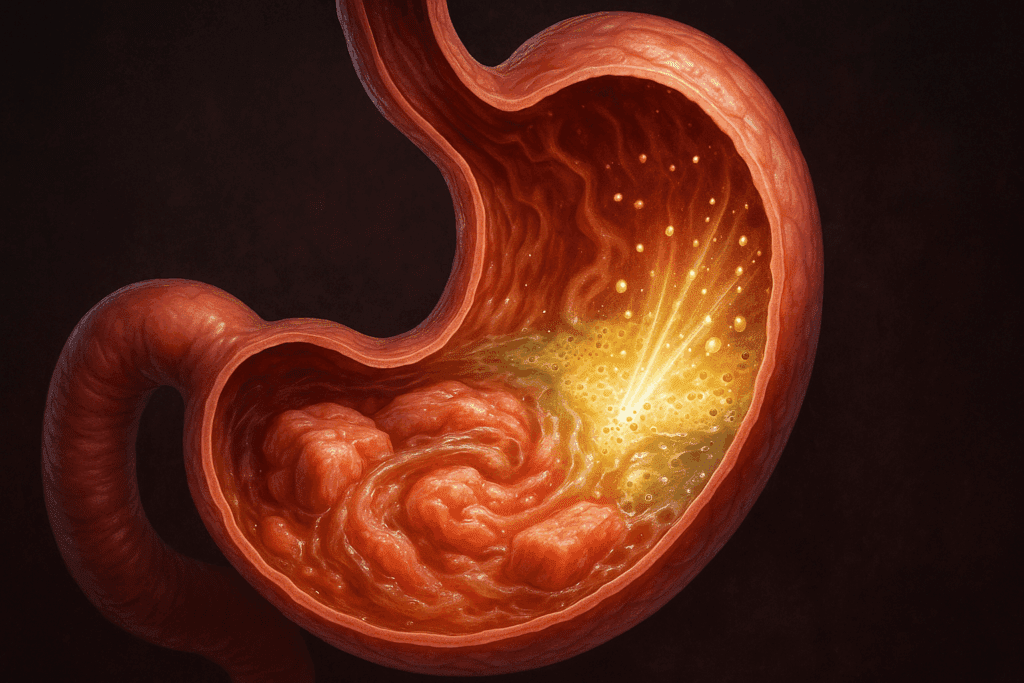

Once food is swallowed, it travels down the esophagus into the stomach, a muscular sac equipped for intense mechanical and chemical activity. The stomach’s powerful contractions churn food into a semi-liquid mass called chyme. This mechanical action is vital for ensuring that food is evenly exposed to gastric secretions.

On the chemical side, the stomach secretes hydrochloric acid (HCl), which lowers the pH and denatures proteins, making them more accessible to digestive enzymes such as pepsin. This enzyme targets protein structures, breaking them down into smaller polypeptides and amino acids. Without this acidic environment, enzymes would not function properly, and the entire system of physically and chemically breaking down food would be disrupted. The stomach also temporarily stores food, releasing it gradually into the small intestine, where further digestion occurs.

The Small Intestine: The Primary Site for Nutrient Absorption

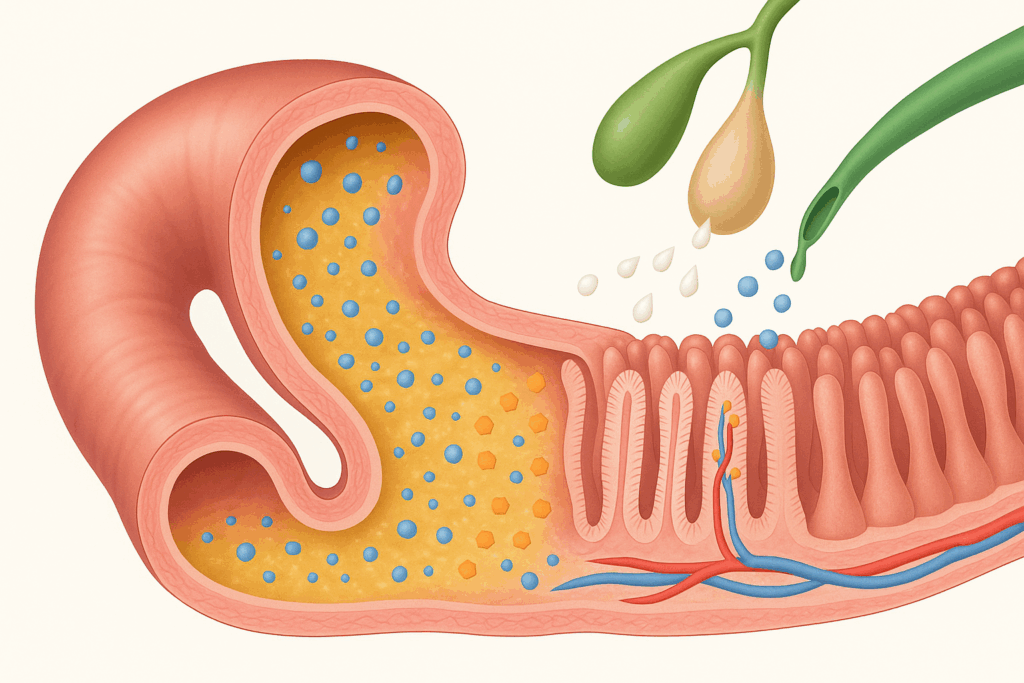

The small intestine is where digestion reaches its peak in both complexity and productivity. This organ, divided into the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, is lined with villi and microvilli that massively increase the surface area available for absorption. Here, digestive enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver play central roles in breaking food down at the molecular level.

Pancreatic enzymes include amylase (for carbohydrates), lipase (for fats), and proteases such as trypsin (for proteins). These enzymes function in a more alkaline environment than the stomach, facilitated by bicarbonate secreted by the pancreas. Meanwhile, bile emulsifies fats, breaking them into smaller droplets that can be more easily digested and absorbed. This phase exemplifies the sophisticated interplay between the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials, ensuring that nutrients are efficiently delivered into the bloodstream for systemic use.

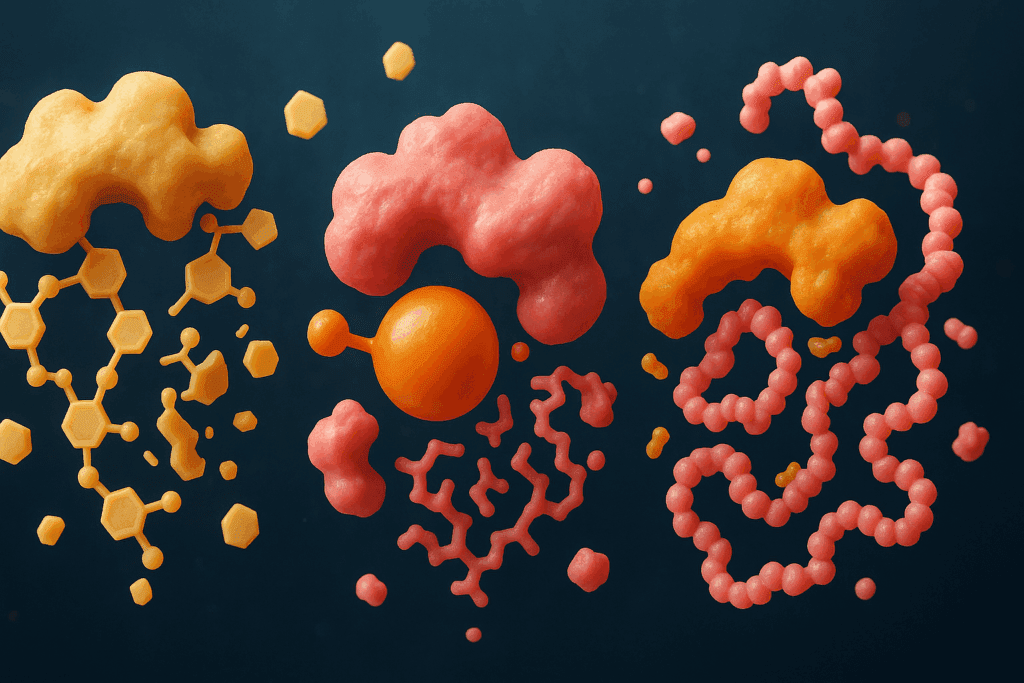

Enzymes: The Unsung Heroes of Chemical Digestion

Without enzymes, chemical digestion would not be possible. These biological catalysts speed up the breakdown of complex food molecules without being consumed in the process. Each enzyme is highly specific: amylase acts on starches, proteases act on proteins, and lipases act on fats. They are also sensitive to temperature and pH, making the digestive system’s environment a key factor in enzymatic efficiency.

The importance of enzymes extends beyond the pancreas. The lining of the small intestine also secretes enzymes such as lactase (which breaks down lactose), sucrase (for sucrose), and maltase (for maltose). A deficiency in any one of these enzymes can lead to incomplete digestion and gastrointestinal distress. This is why a deeper understanding of how enzymes contribute to the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials can illuminate common digestive disorders and potential interventions.

The Liver and Gallbladder: Supporting Fat Digestion

The liver produces bile, a substance critical for digesting fats. Bile contains bile salts that emulsify large fat globules into smaller micelles, increasing the surface area for pancreatic lipase to act upon. This function is purely chemical but supports the mechanical process by enhancing enzyme access to substrates. The gallbladder stores and releases bile in response to signals from the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK), which is triggered by the presence of fats in the duodenum.

By facilitating the breakdown and absorption of dietary fats, the liver and gallbladder highlight an essential component of the chemically breaking down food essentials. Disruption in bile flow—due to gallstones, liver disease, or inflammation—can significantly impair fat digestion, resulting in symptoms like bloating, diarrhea, or nutrient deficiencies.

Large Intestine and the Microbiome: The Final Phase of Digestion

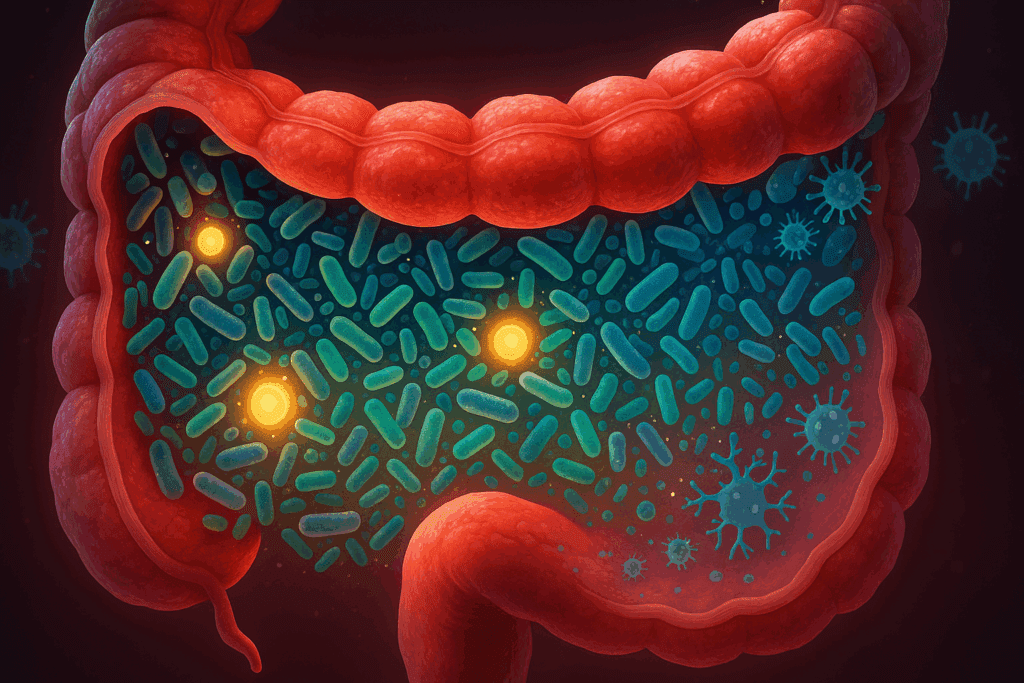

While the small intestine is the star player in nutrient absorption, the large intestine—or colon—has a quieter but equally essential role. Here, water and electrolytes are reabsorbed, and indigestible materials are compacted into stool. More importantly, this is where the gut microbiome thrives.

Comprising trillions of bacteria, the microbiome ferments undigested carbohydrates and fibers into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate and propionate, which support colon health and modulate inflammation. This process is not just a biological curiosity—it’s a cornerstone of preventive health. A robust microbiome assists in the physically and chemically breaking down food that resists human digestion, offering an added layer of nutrient extraction and systemic benefit.

The Nervous and Endocrine Systems: Regulating Digestive Efficiency

The digestive system does not operate in isolation—it is intricately regulated by the nervous and endocrine systems. The enteric nervous system, sometimes referred to as the “second brain,” controls peristalsis, enzyme release, and blood flow to digestive organs. Meanwhile, hormones such as gastrin, secretin, and CCK coordinate the timing and intensity of digestive secretions.

Stress, anxiety, and poor sleep can dysregulate this system, leading to issues like acid reflux, bloating, or even irritable bowel syndrome. Understanding how these systems interact with the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials provides a more holistic view of digestive health, emphasizing the importance of emotional well-being alongside dietary habits.

Lifestyle Factors That Influence Digestion

Several lifestyle choices can either support or hinder digestive efficiency. For example, hydration is essential for dissolving nutrients and transporting waste. Fiber supports regular bowel movements and feeds beneficial bacteria. Chewing thoroughly can even signal hormonal satiety responses, potentially reducing caloric intake and supporting metabolic health.

Conversely, eating too quickly, consuming heavily processed foods, or drinking excessive alcohol can impair the body’s ability to digest food properly. Recognizing how everyday behaviors affect the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials empowers individuals to make smarter decisions that promote long-term health.

Common Digestive Disorders and the Breakdown Process

When digestion fails, symptoms are often quick to appear—bloating, cramping, nutrient deficiencies, and fatigue are just a few. Conditions like lactose intolerance, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and chronic pancreatitis each interfere with specific aspects of physical or chemical digestion. Whether through enzyme insufficiency, inflammation, or structural damage, these disorders disrupt the body’s ability to break down and absorb nutrients.

Treatment often involves identifying which part of the physically and chemically breaking down food process is impaired, and supporting it through diet, supplementation, or medication. In this way, a deeper understanding of digestion not only informs wellness strategies but also enhances medical care.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Understanding the Physically and Chemically Breaking Down Food Essentials

1. How does meal temperature impact the way your body breaks down food? Temperature plays a subtle but impactful role in digestion, particularly in the way enzymes function during the physically and chemically breaking down food process. Enzymes, which drive chemical digestion, are temperature-sensitive and perform best at normal body temperature. Consuming extremely cold or hot foods may momentarily slow enzymatic activity, potentially delaying nutrient breakdown in the stomach and small intestine. While the body quickly works to neutralize these temperature differences, habitual intake of overly hot or cold meals might cause transient discomfort or mild inefficiencies in digestion. For those seeking optimal function of the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials, maintaining meals at moderate temperatures may help support smoother digestive transitions.

2. Can your posture during and after meals influence digestion efficiency? Yes, posture has a notable effect on how effectively the body completes the process of physically and chemically breaking down food. Slouching during or after meals can compress abdominal organs and reduce gastrointestinal motility, making it harder for food to move smoothly through the digestive tract. In contrast, sitting upright encourages proper alignment of the esophagus, stomach, and intestines, allowing gravity to aid in peristalsis and enzymatic distribution. Some studies suggest that light movement after eating, such as a gentle walk, can further enhance digestive secretions and mechanical propulsion. These small shifts in behavior can support the optimal expression of the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials in everyday life.

3. How does age affect the body’s ability to digest food efficiently? Aging brings about gradual changes in nearly every organ system, including those involved in digestion. The stomach may produce less acid over time, which impacts the chemically breaking down food essentials, particularly in protein digestion. Similarly, pancreatic enzyme secretion may decrease, impairing the breakdown of fats and carbohydrates. Physical changes, such as reduced intestinal motility or weakened esophageal muscles, can further slow the process. Older adults may also be more prone to digestive discomforts like constipation or bloating, making it especially important to understand how the physically and chemically breaking down food mechanisms adapt with age—and how dietary strategies such as smaller meals, enzyme supplements, or increased fiber can compensate.

4. What role do emotions play in digestive performance? Emotions profoundly influence the gut-brain connection, which directly impacts the physically and chemically breaking down food process. Chronic stress, anxiety, or even acute emotional distress can alter hormone levels and nerve signals, decreasing enzyme production and slowing gut motility. This can lead to indigestion, acid reflux, or changes in bowel habits. Emotional dysregulation also affects the microbiome, which plays a supportive role in both chemical digestion and the final fermentation phase in the colon. Cultivating emotional well-being is not just good for mental health; it plays a tangible role in sustaining the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials over time.

5. Are there benefits to occasionally resting the digestive system through intermittent fasting? Intermittent fasting offers physiological rest to the digestive system, allowing for a temporary pause in the constant workload of physically and chemically breaking down food. During fasting, digestive organs shift focus from secretion to repair and regeneration. This break may improve insulin sensitivity, reduce systemic inflammation, and support a healthier microbiome. However, the benefits depend on the individual’s overall health status and how the fasting is structured. When practiced safely, intermittent fasting may optimize long-term digestive efficiency, reinforcing the vitality of the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials by giving the body time to recalibrate between feeding periods.

6. How does circadian rhythm influence digestion and nutrient breakdown? Circadian biology—the internal body clock—significantly affects how the body handles food. Enzyme secretion, gastric motility, and hormone release follow a daily rhythm, peaking during the day and slowing at night. Disrupting this cycle by eating late at night or irregularly can impair the physically and chemically breaking down food process, as the body is less primed for digestion outside of daylight hours. Emerging research shows that aligning meal times with the body’s natural rhythms can improve metabolic health, nutrient absorption, and overall gastrointestinal performance. Synchronizing eating patterns with the circadian rhythm may therefore enhance the efficiency of the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials.

7. Can physical activity enhance digestion beyond just calorie expenditure? Absolutely. While exercise is often celebrated for its calorie-burning effects, it also enhances many components of digestion. Regular movement stimulates peristalsis—the wave-like contractions that push food through the digestive tract—which assists in the physical aspect of food breakdown and waste elimination. Exercise also improves blood flow to digestive organs, helping distribute enzymes and hormones necessary for the chemically breaking down food essentials. Moreover, active individuals often report fewer symptoms of bloating and constipation, suggesting that moderate exercise complements and supports the body’s full digestive cycle. This highlights how physical activity is integrally linked to the physically and chemically breaking down food process.

8. Are digestive enzyme supplements effective for people with normal digestive health? For most individuals with healthy digestion, the body naturally produces adequate enzymes to break down food. However, under certain conditions—such as high-fat meals, rapid eating, or mild enzyme insufficiencies—supplementing with digestive enzymes may support or enhance the chemically breaking down food essentials. For instance, lactase supplements can help those who are lactose-intolerant, even if their overall digestive health is intact. Additionally, plant-based enzymes like bromelain or papain can provide temporary relief from post-meal bloating. While not universally necessary, occasional supplementation can optimize the efficiency of physically and chemically breaking down food, especially during dietary challenges or digestive transitions.

9. How do ultra-processed foods interfere with digestion and nutrient absorption? Ultra-processed foods are often low in fiber, rich in artificial additives, and structurally altered in ways that can bypass normal digestive processes. These foods require less effort to break down physically, which may blunt satiety signals and disrupt hormonal responses. Chemically, they can lack essential cofactors that support enzyme function, potentially leading to incomplete nutrient breakdown and absorption. Over time, a diet high in ultra-processed foods may weaken the gut lining and disturb the microbiome, both of which are critical to the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials. Prioritizing whole, minimally processed foods allows the digestive system to engage fully in both physical and chemical digestion, preserving digestive integrity.

10. What innovations are emerging in the science of digestion? Recent advancements in microbiome mapping, enzyme technology, and personalized nutrition are revolutionizing our understanding of digestion. Scientists are now able to sequence individual gut microbiota to identify imbalances that may be hindering the physically and chemically breaking down food process. Wearable biosensors and smart digestive trackers are also being developed to monitor enzyme activity and gut motility in real time. Additionally, precision supplements tailored to an individual’s digestive profile are entering the market, promising more targeted support for food breakdown and absorption. As research continues, these innovations will likely refine our understanding of the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials, offering new ways to enhance digestive health in clinically meaningful ways.

Conclusion: Empowering Wellness Through Digestive Awareness

Gaining a deeper understanding of how the body physically and chemically breaks down food is not just a scientific pursuit—it is a key to unlocking better health. The digestive system is an elegant, highly orchestrated machine that transforms what we eat into the energy and materials our bodies need to thrive. From the mechanical grinding in the mouth to the chemical transformations in the stomach and intestines, every step in the process is essential to our vitality.

Recognizing the physically and chemically breaking down food essentials allows us to support this system with intentional dietary and lifestyle choices. Whether it’s by eating more fiber, staying hydrated, managing stress, or simply chewing more thoroughly, each effort enhances our ability to digest, absorb, and benefit from the foods we consume.

As research continues to shed light on the nuances of digestion and gut health, one message remains constant: supporting your body’s natural ability to break down food is one of the most powerful investments you can make in your long-term wellness. Let this knowledge guide your journey toward optimal nutrition, stronger immunity, and a healthier, more resilient life.

Further Reading:

What to know about chemical digestion