Hypertension, commonly known as high blood pressure, has long been a leading cause of cardiovascular disease worldwide. Despite its prevalence, many people underestimate its long-term consequences or delay seeking treatment until complications emerge. The question often arises: is hypertension a chronic disease, or can it be managed and reversed before becoming a permanent health burden? Understanding the nature, onset, and risks associated with chronic hypertension is crucial to developing early interventions that can improve both longevity and quality of life. As we explore the underlying mechanisms and implications of this condition, we will answer some of the most pressing questions, including when chronic hypertension starts and whether high blood pressure should be considered a chronic condition.

You may also like: Sudden Spikes in Blood Pressure: What Can Cause a Sudden Increase and When to Seek Medical Attention

Defining Hypertension in the Modern Medical Context

Hypertension refers to consistently elevated blood pressure levels above the normal threshold, which is typically set at 120/80 mmHg. While occasional fluctuations in blood pressure can be a natural response to stress, exercise, or illness, sustained elevations pose a significant threat to the cardiovascular system. Modern guidelines classify blood pressure readings into categories—normal, elevated, stage 1 hypertension, and stage 2 hypertension—allowing clinicians to determine when intervention is warranted. In many cases, patients are unaware of their condition, earning hypertension the nickname “the silent killer.”

In recent years, the medical community has debated whether high blood pressure qualifies as a chronic disease. Most experts now agree that it does. In fact, the answer to the question “is hypertension a chronic disease” is increasingly understood through the lens of long-term disease management. Much like diabetes or asthma, hypertension typically requires ongoing lifestyle adjustments, pharmacologic treatment, and continuous monitoring to prevent complications. Once diagnosed, the condition does not simply resolve on its own, and without proper treatment, it tends to worsen over time.

The Pathophysiology of Chronic Hypertension

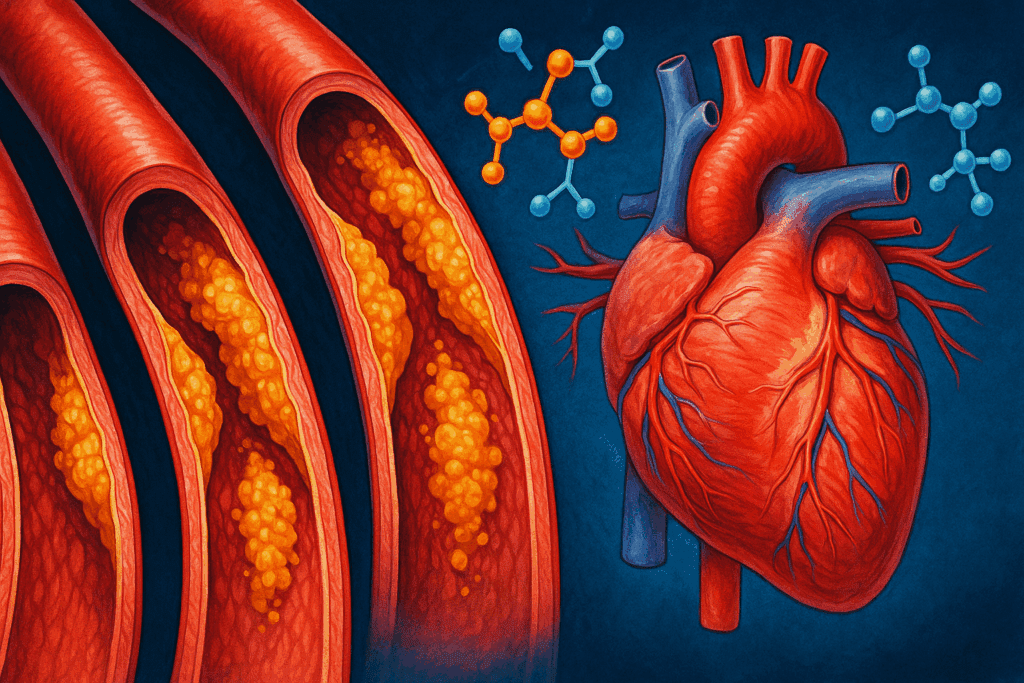

Chronic hypertension develops through a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and physiological factors. One of the primary mechanisms involves increased resistance in the peripheral arteries, which forces the heart to work harder to circulate blood throughout the body. Over time, this increased workload leads to structural changes in the heart and blood vessels, such as left ventricular hypertrophy, arterial thickening, and reduced vascular elasticity.

Another key component of chronic hypertension is the role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), which regulates fluid balance and blood pressure. In individuals predisposed to hypertension, this system may become overactive, leading to sodium retention, increased blood volume, and further elevation of blood pressure. Moreover, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance are often present in people with long-standing hypertension, adding to the disease’s complexity.

Understanding when chronic hypertension starts can help clinicians and patients take preventive measures. While elevated blood pressure may first appear during periods of stress or illness, persistent readings above 130/80 mmHg, especially when documented across multiple visits, indicate the beginning stages of chronic hypertension. Early recognition is vital, as untreated high blood pressure gradually damages organs such as the kidneys, brain, and heart.

Is High Blood Pressure a Chronic Condition?

To address the question “is high blood pressure a chronic condition,” we must examine the characteristics that define chronic diseases. A condition is generally considered chronic if it is long-lasting, progresses over time, and requires ongoing medical care. Hypertension fits this definition precisely. Unlike acute conditions, which resolve after a short period or with treatment, chronic high blood pressure does not typically return to normal without sustained intervention.

Patients with chronic hypertension often face a lifetime of blood pressure management. This may include taking medications such as ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, or calcium channel blockers, depending on the individual’s specific risk factors and comorbidities. Lifestyle changes—like reducing sodium intake, maintaining a healthy weight, increasing physical activity, and moderating alcohol consumption—are also central to managing the condition.

Given these realities, it is accurate and medically appropriate to refer to high blood pressure as a chronic condition. Framing it this way not only improves public awareness but also emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and long-term care. Patients are more likely to adhere to treatment plans when they understand the persistent nature of their condition.

The Early Warning Signs and Risk Factors of Chronic Hypertension

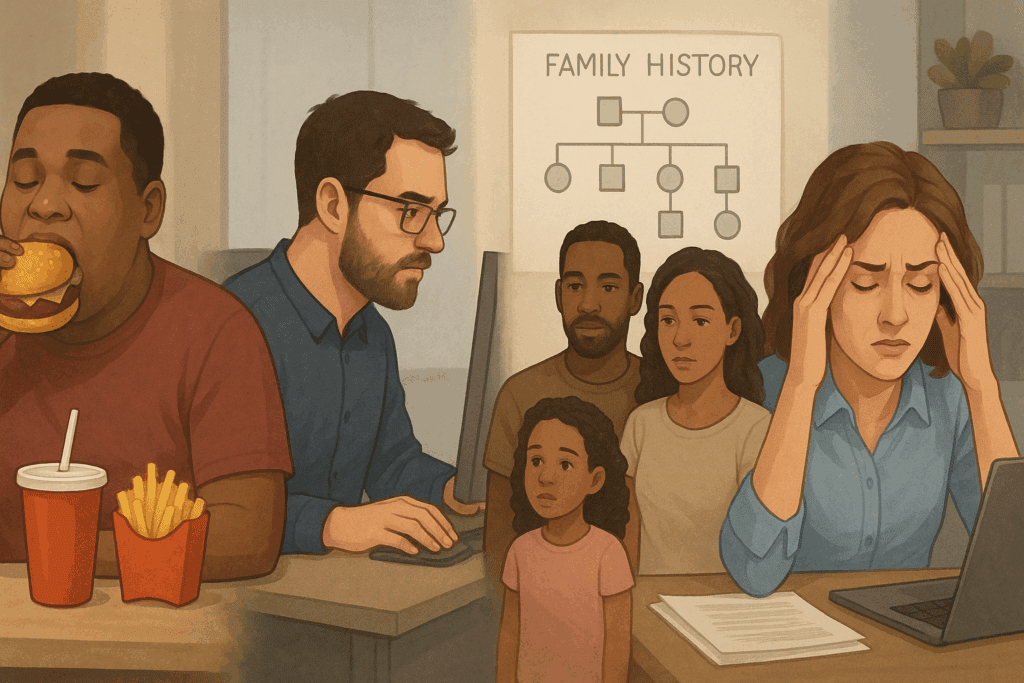

Many individuals with chronic hypertension do not experience symptoms until complications have already developed. However, there are several warning signs and risk factors that may indicate the onset of high blood pressure. Family history plays a significant role; individuals with close relatives who have hypertension are more likely to develop the condition themselves. Other risk factors include obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, smoking, excessive alcohol intake, poor diet, and chronic stress.

When chronic hypertension starts, it often does so gradually and silently. People may notice symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, blurred vision, or shortness of breath, but these are usually subtle and easy to overlook. Routine blood pressure monitoring is therefore essential, especially for those with known risk factors. It is during these early stages that lifestyle interventions can be most effective in reversing or slowing disease progression.

Another indicator of early hypertension is prehypertension, a condition defined by systolic readings between 120 and 129 mmHg and diastolic readings below 80 mmHg. While not yet classified as chronic hypertension, this range suggests that the individual is on a trajectory toward the condition. Intervening at this point can significantly alter the course of disease development and may even prevent the need for medication.

How Chronic Hypertension Affects the Body Over Time

The long-term effects of chronic hypertension extend beyond elevated blood pressure numbers. The condition places ongoing strain on the cardiovascular system, leading to significant complications if left unmanaged. Among the most common are heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, and vision loss. Each of these conditions results from the cumulative damage that high blood pressure inflicts on the body’s blood vessels and organs.

In the heart, chronic hypertension contributes to left ventricular hypertrophy, a thickening of the heart muscle that can lead to heart failure. It also increases the risk of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. In the brain, uncontrolled high blood pressure is a major risk factor for ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, as well as cognitive decline and dementia.

The kidneys are particularly vulnerable to chronic hypertension. High blood pressure damages the delicate filtering units called nephrons, reducing kidney function and potentially leading to end-stage renal disease. This necessitates dialysis or kidney transplantation in severe cases. Additionally, damage to the retinal arteries in the eyes can result in hypertensive retinopathy, which may cause vision impairment or blindness.

The question “is hypertension a chronic disease” becomes even more pressing when considering these long-term consequences. Recognizing the systemic nature of the condition underscores the need for comprehensive, long-term care and monitoring.

Diagnosis and Clinical Criteria for Chronic Hypertension

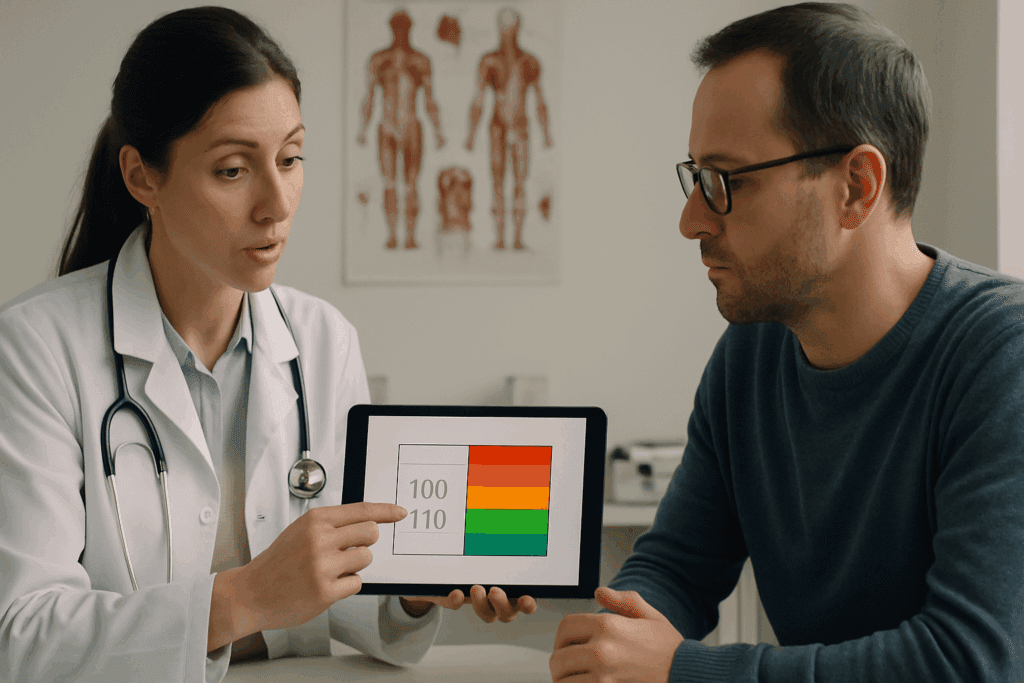

Diagnosing chronic hypertension requires more than a single high reading at a doctor’s office. Clinicians typically use multiple measurements taken over several visits to confirm the diagnosis. Blood pressure should be measured using a properly calibrated device, with the patient seated comfortably and relaxed. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or home measurements may also be used to eliminate the effects of white-coat syndrome.

To determine when chronic hypertension starts, clinicians look for consistent readings above the 130/80 mmHg threshold, in accordance with guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. If elevated readings are observed repeatedly over a span of weeks or months, a diagnosis of chronic hypertension is made. This diagnosis is often accompanied by an evaluation of the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk, including cholesterol levels, glucose tolerance, and the presence of other comorbidities.

Blood and urine tests, electrocardiograms (ECG), and imaging studies may also be conducted to assess for damage to target organs. The goal is not only to confirm the presence of chronic hypertension but to understand its severity and the degree of systemic involvement. Early diagnosis allows for timely treatment, which can dramatically reduce the risk of serious complications down the line.

Management Strategies for Long-Term Blood Pressure Control

Once a diagnosis is established, the primary focus shifts to controlling blood pressure and mitigating associated risks. Effective management typically involves a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies. Medications are chosen based on the patient’s specific needs, underlying conditions, and response to treatment. Diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers are among the most commonly prescribed.

Lifestyle modifications are equally important. These include adopting a heart-healthy diet, such as the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, which emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and low-fat dairy. Reducing sodium intake, increasing potassium-rich foods, and maintaining a healthy weight can significantly improve blood pressure control.

Exercise plays a pivotal role as well. Regular physical activity, such as brisk walking, swimming, or cycling, helps lower blood pressure and improves cardiovascular fitness. Stress management techniques, including mindfulness, yoga, and cognitive-behavioral therapy, are beneficial for patients whose hypertension is exacerbated by chronic stress.

Understanding that high blood pressure is a chronic condition helps patients commit to long-term changes. Education and support from healthcare providers are essential for fostering adherence to treatment plans and encouraging consistent follow-up. As patients take ownership of their condition, outcomes improve and the risk of complications declines.

The Role of Preventive Care and Public Health Initiatives

Preventing chronic hypertension is a public health priority, given its widespread prevalence and far-reaching impact. Community-based screening programs, public education campaigns, and access to affordable healthcare are all critical components of prevention. Early identification of individuals at risk allows for timely intervention, reducing the burden of disease on individuals and healthcare systems alike.

Health professionals must also work to dispel common misconceptions. Many people still ask, “is high blood pressure a chronic condition?”—a question that reflects a lack of awareness about the disease’s persistence and seriousness. By framing hypertension as a lifelong condition, healthcare providers can help shift public perception and motivate proactive health behaviors.

Policy initiatives aimed at reducing sodium in processed foods, promoting physical activity, and ensuring access to healthy food choices are powerful tools for reducing the incidence of chronic hypertension. In this context, public health efforts complement individual medical care, creating a more holistic and sustainable approach to cardiovascular health.

Genetics, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Influences on Hypertension

Genetic predisposition plays a notable role in the development of chronic hypertension. Individuals with a family history of the condition are more likely to experience early onset, often before age 40. Certain ethnic groups, particularly African Americans, are disproportionately affected and may develop more severe forms of hypertension at younger ages. This heightened susceptibility is believed to result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and socioeconomic factors.

Socioeconomic status also influences the incidence and management of hypertension. Limited access to healthcare, nutritious food, safe environments for exercise, and educational resources creates barriers to effective prevention and treatment. Addressing these disparities requires targeted interventions that prioritize equity and inclusivity.

Understanding when chronic hypertension starts can help healthcare providers offer tailored guidance to those at highest risk. Early screening and culturally competent care can bridge the gap and reduce disparities in health outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions About Chronic Hypertension and Long-Term Cardiovascular Health

1. How does chronic hypertension impact quality of life beyond physical health?

While the physical risks of hypertension are well-documented, its effects on emotional and social well-being are often underestimated. Individuals managing chronic hypertension may experience heightened stress or anxiety related to ongoing monitoring, medication regimens, and fear of complications. These factors can reduce overall life satisfaction, especially when paired with lifestyle restrictions like dietary changes or activity limitations. Additionally, the stigma associated with chronic illness can affect interpersonal relationships and workplace dynamics, leading some patients to conceal their condition. Recognizing that high blood pressure is a chronic condition helps patients frame their experiences within a broader health context and seek support for the psychosocial aspects of disease management.

2. At what age does chronic hypertension typically begin, and can it start earlier than expected?

Contrary to common belief, chronic hypertension starts at increasingly younger ages due to rising obesity rates, poor dietary habits, and high stress levels among adolescents and young adults. Although it was once considered a disease of middle age or older adults, early-onset hypertension is becoming more prevalent. In some cases, children and teenagers with a family history of cardiovascular disease or metabolic disorders begin showing signs of elevated blood pressure in their late teens or early twenties. Early identification is crucial, as it allows for intervention before vascular damage becomes irreversible. Understanding when chronic hypertension starts enables healthcare professionals to develop targeted preventive strategies for younger populations.

3. What role does sleep quality play in the development of chronic hypertension?

Sleep is a vital but often overlooked factor in the regulation of blood pressure. Poor sleep quality, particularly from sleep apnea, insomnia, or frequent nighttime awakenings, can contribute significantly to the development and progression of chronic hypertension. The body’s inability to enter deep, restorative sleep disrupts the natural nocturnal dipping of blood pressure, leading to elevated levels during both night and day. For patients questioning whether high blood pressure is a chronic condition, addressing sleep hygiene can be an effective part of long-term management. Sleep studies and behavioral interventions may reveal treatable sleep disturbances that could reduce blood pressure and improve overall cardiovascular outcomes.

4. How do stress and mental health influence whether hypertension becomes chronic?

Chronic psychological stress is a powerful risk factor in the transition from transient to chronic hypertension. Long-term activation of the sympathetic nervous system elevates heart rate and constricts blood vessels, leading to persistently high blood pressure. Individuals in high-pressure work environments or those experiencing chronic anxiety or depression are at greater risk of developing sustained hypertension. Recognizing that hypertension is a chronic disease highlights the importance of integrating mental health support into hypertension care. Techniques such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, meditation, and biofeedback have shown promise in reducing stress-induced hypertensive responses.

5. Are there biomarkers or genetic indicators that predict if high blood pressure will become chronic?

Emerging research has identified several genetic polymorphisms and circulating biomarkers that may help predict the likelihood of progression to chronic hypertension. These include variants in genes regulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, as well as markers of inflammation like C-reactive protein and interleukin-6. While the question “is hypertension a chronic disease” often arises after diagnosis, these biomarkers may soon help clinicians assess risk even before clinical symptoms appear. Personalized medicine approaches that incorporate genetic and molecular data could enable earlier and more tailored interventions. This future-forward approach holds promise for halting the disease in its early stages.

6. How does medication adherence affect the classification of hypertension as a chronic condition?

Medication nonadherence is a leading cause of uncontrolled blood pressure and progression to chronic disease. Some patients stop taking medications when they feel better, not realizing that hypertension often remains asymptomatic while causing silent damage to the cardiovascular system. Inconsistent treatment reinforces the reality that high blood pressure is a chronic condition that requires continuous care—even during periods without noticeable symptoms. Pharmacist-led interventions, digital reminders, and fixed-dose combination therapies are effective tools to improve adherence. Understanding that the management of hypertension parallels other chronic illnesses like diabetes reinforces the need for sustained, lifelong engagement.

7. Can dietary patterns alone reverse chronic hypertension, or is medical treatment always necessary?

While diet plays a critical role in managing hypertension, reversing established chronic hypertension through nutrition alone is uncommon, especially in advanced cases. Diets rich in potassium, magnesium, fiber, and low in sodium—such as the DASH or Mediterranean diet—can substantially lower blood pressure. However, once vascular remodeling and organ damage occur, pharmacological treatment is usually required alongside dietary changes. Individuals asking whether hypertension is a chronic disease must understand that while early dietary intervention may delay its onset, reversing it entirely without medication is rare. A combined approach is typically more effective than relying solely on lifestyle changes.

8. What are the economic and healthcare system implications of labeling hypertension as a chronic disease?

Designating hypertension as a chronic disease has substantial implications for healthcare policy, insurance coverage, and resource allocation. Chronic disease classification ensures that hypertension is prioritized in preventive care programs, chronic disease registries, and population health initiatives. It can also influence patient eligibility for long-term medication coverage, telehealth services, and subsidized lifestyle support programs. Understanding that high blood pressure is a chronic condition drives systems to build infrastructure around monitoring and continuity of care. It also affects workplace health strategies, as employers increasingly support wellness programs aimed at reducing long-term medical costs associated with chronic hypertension.

9. Are digital health technologies effective in preventing chronic hypertension?

Wearable blood pressure monitors, mobile apps, and telehealth platforms are becoming valuable tools in preventing the escalation of early-stage hypertension to chronic disease. These technologies empower patients to track their readings in real time, receive alerts, and engage with their healthcare providers remotely. For individuals at the stage where chronic hypertension starts, early digital intervention can provide critical feedback loops to prevent long-term vascular damage. Many platforms also include dietary guidance, stress reduction modules, and medication reminders. As the conversation around whether hypertension is a chronic disease evolves, digital health may become a central pillar of personalized, proactive care.

10. What are the societal perceptions of chronic hypertension, and how do they affect patient outcomes?

Societal attitudes toward chronic hypertension often downplay its seriousness due to its lack of overt symptoms and gradual onset. Many people fail to realize that hypertension is a chronic disease that demands consistent attention, similar to conditions like cancer or autoimmune disorders. This minimization can lead to underdiagnosis, undertreatment, and poor adherence to medical advice. When patients internalize the idea that high blood pressure is a chronic condition, they are more likely to engage with care plans, seek education, and prioritize preventive measures. Public awareness campaigns and health literacy efforts are essential for shifting perceptions and improving long-term outcomes for those living with chronic hypertension.

A Holistic Approach to Understanding and Managing Chronic Hypertension

Chronic hypertension is more than just a number on a blood pressure monitor; it is a multifaceted condition with deep roots in genetics, lifestyle, and social determinants of health. Answering questions like “is hypertension a chronic disease” or “is high blood pressure a chronic condition” requires a comprehensive understanding of its causes, progression, and consequences. The reality is clear: once elevated blood pressure becomes persistent, it transforms into a lifelong health concern requiring diligent care and proactive management.

The importance of early diagnosis cannot be overstated. By identifying when chronic hypertension starts, healthcare providers can intervene before irreversible damage occurs. Equally critical is public education—ensuring that individuals understand the risks, take preventive steps, and engage with healthcare systems that support long-term wellness.

While medication and lifestyle changes are the cornerstones of management, addressing social and economic disparities is also essential for long-term success. Chronic hypertension does not exist in a vacuum; it is shaped by the world in which we live. A holistic, compassionate approach that integrates medical expertise with public health awareness and community engagement offers the best path forward in controlling this silent but powerful condition.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.