Understanding the debate over what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, is essential to making informed dietary choices. In a world flooded with health advice, conflicting food labels, and dietary fads, deciphering which fats are truly harmful requires a closer look at scientific evidence and expert consensus. Both trans fats and saturated fats have long been classified under the umbrella of “bad and fat” in many nutrition guidelines, but recent research has begun to draw more nuanced conclusions about their relative risks and roles in chronic disease. As more people search for answers to questions like “why are trans fats bad for you?” or “is trans fat good in small doses?”, the need for evidence-based clarity becomes even more urgent. In this article, we explore the health risks associated with both types of fats, examine the kinds of products that are commonly called bad in this context, and offer practical, medically accurate advice for navigating the modern food landscape.

You may also like: Macronutrients vs Micronutrients: What the Simple Definition of Macronutrients Reveals About Your Diet and Health

Trans Fat: The Manufactured Menace

Trans fats are artificially created through a process called hydrogenation, which adds hydrogen to liquid vegetable oils to make them more solid and shelf-stable. This manufacturing innovation revolutionized the food industry in the 20th century, allowing processed foods to last longer while maintaining an appealing texture. However, what initially seemed like a culinary breakthrough eventually emerged as a serious health concern. Numerous studies have confirmed the dangers associated with consuming trans fats, including increased risk of heart disease, systemic inflammation, and insulin resistance. When asked, “is trans fat bad for your health,” the overwhelming expert consensus is a firm yes.

The primary reason why trans fats are bad for you lies in their unique chemical structure, which makes them particularly harmful to cholesterol levels. Trans fats not only raise levels of LDL (low-density lipoprotein, or “bad” cholesterol), but also lower HDL (high-density lipoprotein, or “good” cholesterol), creating a double jeopardy for cardiovascular health. Unlike some other dietary fats that may have nuanced or context-specific health effects, trans fats offer no known physiological benefit. In fact, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declared trans fats not “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS) for human consumption and implemented widespread bans beginning in 2015. This means that even in small amounts, the answer to “is trans fat good?” remains an emphatic no from health authorities.

The scientific clarity around trans fats makes them one of the few food components that nutritionists almost universally agree should be avoided entirely. Even minuscule amounts have been linked to adverse health outcomes, which is why current guidelines recommend keeping trans fat intake as close to zero as possible. Despite regulatory efforts, trace amounts may still be found in some baked goods, fried foods, and even non-dairy coffee creamers, making label reading an essential habit for health-conscious consumers.

Saturated Fats: Controversial but Contextual

In contrast to trans fats, the narrative surrounding saturated fats is far more complex. Saturated fats are naturally occurring fats found in animal products like butter, cheese, and red meat, as well as some plant-based sources such as coconut and palm oils. For decades, saturated fat was vilified as a major contributor to heart disease, primarily due to its ability to raise LDL cholesterol levels. However, newer research has challenged the universality of this claim, suggesting that the health effects of saturated fats may depend heavily on the dietary context in which they are consumed.

When people ask what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, many experts are quick to point out that saturated fats do not share the same unequivocal harm profile as trans fats. While saturated fats can elevate LDL cholesterol, they do not necessarily reduce HDL cholesterol the way trans fats do. Moreover, certain saturated fat-rich foods, like full-fat dairy or dark chocolate, have been associated with neutral or even positive health outcomes in observational studies. This has led to a reevaluation of whether saturated fat, in and of itself, should be universally categorized as a dietary villain.

Still, it would be premature to fully exonerate saturated fats. Meta-analyses continue to show that high intake of saturated fat, especially from processed and red meats, is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease. However, these effects are less pronounced when saturated fat is consumed in moderation and within a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and fiber. Thus, while the question “is trans fat bad?” has a straightforward answer, the health implications of saturated fats require more nuance and individualization.

What Kinds of Products Are Commonly Called Bad?

Understanding what kinds of products are commonly called bad in the realm of dietary fats can help consumers navigate the grocery aisle with greater awareness. Products high in trans fats often include margarine sticks, commercially baked pastries, packaged cookies, crackers, microwave popcorn, and deep-fried fast foods. Even after regulatory bans, some imported or older products may still contain industrial trans fats, particularly in regions where food labeling standards are less stringent.

Saturated fats, while often occurring naturally, are abundant in processed meats such as sausages, bacon, and deli cuts, as well as in high-fat dairy items like cream, butter, and certain cheeses. Baked goods made with butter or palm oil can also be significant sources. Though not inherently harmful in small amounts, these products become more problematic when they dominate a person’s daily caloric intake. This is especially concerning in Western diets, which tend to overemphasize these ingredients at the expense of more nutrient-dense whole foods.

The label “bad and fat” is often applied to both trans fats and saturated fats when they appear in ultra-processed foods, which are engineered for taste, shelf-life, and marketability rather than nutritional quality. These foods tend to be high in calories, low in fiber, and often loaded with added sugars and sodium. The combined dietary effect of these components, rather than fat content alone, is what drives much of the chronic disease burden seen globally. Therefore, knowing what kinds of products are commonly called bad allows individuals to make better decisions not only based on fat content but also on overall nutritional value.

How Trans and Saturated Fats Affect Heart Health

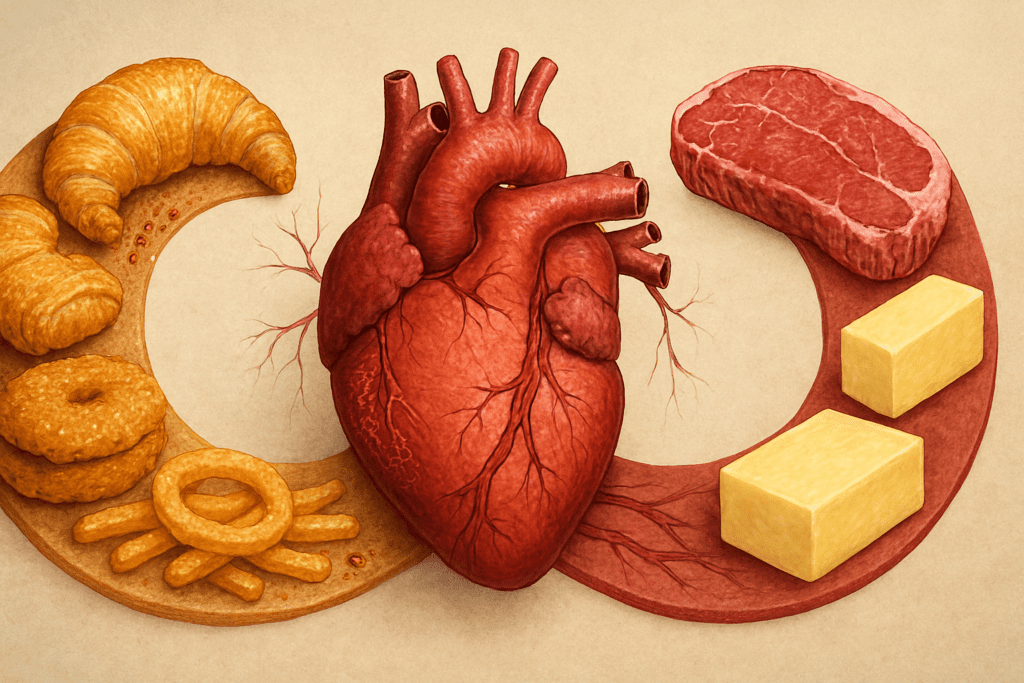

When evaluating the question of what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, heart health is often the central concern. Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, and dietary fat plays a pivotal role in shaping risk. Trans fats have been consistently shown to promote atherosclerosis, a condition characterized by the buildup of plaque in the arteries, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes. Their negative impact on cholesterol profiles further amplifies this risk, making them particularly detrimental to long-term cardiovascular health.

Saturated fats, by comparison, present a more ambiguous picture. While they can elevate LDL cholesterol, which is a known risk factor for heart disease, they also raise HDL cholesterol to some extent. This dual effect has prompted some researchers to argue that saturated fats may not be as dangerous as once believed, especially when consumed in moderation and in the context of a whole-foods-based diet. That said, replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats—particularly polyunsaturated fats found in nuts, seeds, and fatty fish—has been associated with reduced cardiovascular events in numerous clinical trials.

It’s also important to consider the food matrix, or the combination of nutrients and compounds present in a given food, when evaluating its health impact. For instance, cheese contains saturated fat but also provides calcium, protein, and probiotics, which may counterbalance some of its negative effects. Conversely, a processed meat product containing saturated fat, preservatives, and sodium may amplify cardiovascular risk. Thus, the source of fat matters just as much as the type, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive view rather than a reductionist one.

The Role of Dietary Context and Lifestyle Factors

Context is crucial when analyzing whether saturated or trans fats are more harmful. An individual who consumes saturated fat as part of a balanced, Mediterranean-style diet rich in vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and healthy fats may not face the same risks as someone whose diet is predominantly composed of fast food and processed snacks. Lifestyle factors such as physical activity, sleep quality, and stress levels also influence how the body metabolizes and responds to dietary fats.

Furthermore, genetic factors can modify an individual’s response to saturated fat. Some people are more sensitive to dietary cholesterol and saturated fat due to inherited lipid disorders or metabolic conditions. For these individuals, limiting saturated fat becomes even more critical. Meanwhile, there is no known genetic or biological context in which trans fats can be considered safe or beneficial, reinforcing the conclusion that trans fats are universally harmful regardless of diet or lifestyle.

The rise of plant-based eating patterns has also shifted the focus toward replacing animal fats with plant-derived sources. Diets emphasizing whole plant foods, including avocados, olive oil, nuts, and seeds, have been shown to support cardiovascular health, weight management, and metabolic balance. These diets naturally reduce intake of both trans and saturated fats while enhancing the consumption of essential nutrients and antioxidants, offering a viable strategy for those looking to minimize their intake of what are commonly called “bad” fats.

Consumer Confusion and Food Labeling Challenges

One of the most significant barriers to making healthier fat choices is the persistent confusion surrounding food labels. Products labeled as “trans fat free” may legally contain up to 0.5 grams of trans fat per serving in the United States. This loophole allows small amounts of trans fats to remain hidden in the diet, particularly if consumers eat multiple servings of a given product. As a result, reading ingredient lists for partially hydrogenated oils—a key indicator of trans fat content—is crucial.

Saturated fat labeling presents its own challenges. Foods may be labeled as “low in saturated fat” while still containing significant amounts when multiple servings are consumed. Moreover, many people lack a clear understanding of the recommended daily limits for these fats, further complicating efforts to eat healthfully. The American Heart Association recommends that saturated fat comprise no more than 5% to 6% of total daily calories, while trans fat should be avoided entirely. These figures often get lost amid marketing claims and nutritional buzzwords, highlighting the need for greater consumer education.

Educational campaigns, clearer labeling, and consistent guidelines from health authorities can go a long way toward addressing this confusion. Until then, consumers must rely on a combination of nutrition knowledge and critical thinking to navigate their choices. Asking questions like “is trans fat bad even in trace amounts?” or “what kinds of products are commonly called bad and why?” can serve as a foundation for more informed decision-making.

Balancing Fat Intake for Long-Term Health

Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate all fat from the diet, but to optimize fat intake for better health outcomes. Unsaturated fats, including both monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, should form the foundation of dietary fat intake. These fats support brain function, hormone production, and cell integrity, while also reducing the risk of chronic diseases when they replace saturated and trans fats.

While saturated fats can have a place in a balanced diet, they should be consumed mindfully and preferably from whole food sources rather than processed ones. Conversely, trans fats have no place in a healthful diet and should be avoided altogether. This distinction makes it easier to answer the question of what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats. The scientific and clinical evidence overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that trans fats are more harmful and should be entirely excluded.

For individuals seeking to improve their diet, the best strategy is to emphasize whole, minimally processed foods, and to use cooking oils like olive or canola instead of butter or lard. Choosing lean protein sources, incorporating nuts and seeds, and favoring baked over fried foods can significantly reduce both saturated and trans fat intake. By adopting such strategies, it becomes easier to move away from what kinds of products are commonly called bad and toward a diet that promotes longevity and vitality.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Trans Fats, Saturated Fats, and Their Impact on Health

1. Can small amounts of trans fat still pose a health risk?

Yes, even trace amounts of trans fat can be harmful over time. Many consumers assume that small doses are inconsequential, but the cumulative effects of eating products with hidden trans fats can lead to long-term health consequences. This is one reason why dietitians often advise against trying to rationalize whether is trans fat good in limited quantities—because it’s not. Scientific evidence consistently supports the view that any intake increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, even if consumed occasionally. If you’re wondering what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, the unequivocal answer remains that trans fats are worse due to their impact on both LDL and HDL cholesterol levels.

2. Are there any natural sources of trans fats, and do they carry the same risks?

Interestingly, small amounts of trans fats do occur naturally in the fat of ruminant animals like cows and sheep. These trans fats differ structurally from industrially produced ones, but the question “is trans fat bad” still applies. Research suggests that natural trans fats might be less harmful than artificial types, but there is still caution surrounding their consumption. Because the amount in natural sources is typically very low, they are not a major dietary concern. However, if your goal is to fully avoid what kinds of products are commonly called bad due to unhealthy fats, reducing both artificial and natural trans fats is a wise precaution.

3. How does the public’s perception of “bad and fat” affect dietary behavior?

The concept of “bad and fat” often leads people to fear all fats equally, which can result in misguided food choices. For example, someone may avoid healthy fats from nuts or avocado while still consuming heavily processed low-fat snacks that contain hidden sugars or additives. This misunderstanding complicates the conversation about what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, because the nuance gets lost. Clear public health messaging must distinguish between harmful fats and beneficial ones to empower informed choices. Educating people on why trans fats are bad for you and how to identify them is a key step toward improving national dietary habits.

4. Are there any psychological factors driving consumption of harmful fats?

Yes, emotional eating patterns and reward-seeking behaviors can play a significant role in the overconsumption of foods high in trans and saturated fats. Many products loaded with these fats are engineered for sensory pleasure, often triggering dopamine release in the brain. This neurochemical response creates a feedback loop that encourages repeated consumption, even when individuals know is trans fat bad. The issue becomes more complex when people associate indulgent foods with comfort, further reinforcing cravings. Understanding these psychological cues is important for reducing dependency on what kinds of products are commonly called bad in both clinical and lifestyle contexts.

5. Are trans fats still present in the food supply despite regulatory bans?

Although trans fats have been largely phased out due to FDA regulations, they haven’t been eradicated entirely. The labeling loophole that allows manufacturers to claim “zero trans fat” for products with less than 0.5 grams per serving means some foods still contain them. Therefore, it remains crucial to read ingredient lists carefully to spot partially hydrogenated oils. Many consumers assume that if a product is on the shelf, it must be safe, but that doesn’t answer the lingering question of why are trans fats bad for you—especially when even trace exposure adds up. For those questioning what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, this hidden presence makes trans fats uniquely deceptive and dangerous.

6. How can we practically avoid trans fats without becoming obsessive about food labels?

One of the most effective ways to sidestep the constant label scrutiny is to shift your diet toward whole, minimally processed foods. Items like fresh vegetables, legumes, lean proteins, and whole grains naturally contain none of the substances associated with bad and fat. When you reduce dependence on packaged goods, you simultaneously eliminate the majority of dietary sources of trans fats. For anyone wondering, “is trans fat good in moderation?”, the answer is easier to maintain when your diet is rooted in foods that never contained trans fats to begin with. The key is to make health-conscious eating sustainable rather than perfectionistic.

7. Why do food manufacturers continue to produce foods with unhealthy fats?

Despite known risks, some manufacturers continue using unhealthy fats for economic and practical reasons. Trans fats improve shelf life and texture, making them attractive for mass production. Unfortunately, many of what kinds of products are commonly called bad—like pastries, frozen meals, and snack foods—still rely on these fats for commercial viability, especially in countries with looser regulations. This raises continued public health concerns and reinforces the need to question, “is trans fat bad for all populations?” The answer lies in global food policy reform and consumer demand for transparency and better-quality ingredients.

8. How does the debate around saturated fats confuse the issue?

The nutritional debate over saturated fats often creates confusion around what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, especially as new research emerges. While saturated fats are no longer universally demonized, the pendulum sometimes swings too far, causing people to believe all saturated fats are harmless. This can blur the line between foods that may be consumed in moderation and those that should be limited. The continued questioning of “is trans fat good” or bad clouds judgment even more when paired with inconsistent messaging about saturated fat. Critical thinking and evidence-based guidance are necessary to cut through the noise.

9. What are some cultural or socioeconomic barriers to reducing bad fats in the diet?

Access and affordability are major barriers when it comes to improving fat quality in one’s diet. Communities with limited access to fresh food often rely on ultra-processed, shelf-stable products—many of which are among what kinds of products are commonly called bad. Additionally, time constraints, lack of nutrition education, and cultural food preferences may influence reliance on these convenient yet unhealthy choices. This is especially problematic in areas where asking “is trans fat bad” is not a common part of food literacy. Addressing this requires systemic solutions that go beyond individual behavior, including public policy changes, educational outreach, and community-based health initiatives.

10. What innovations or trends are helping reduce our reliance on harmful fats?

The food industry is slowly adapting to consumer demand for healthier alternatives by developing new fat sources and cooking technologies. Innovations like algae oil, high-oleic sunflower oil, and even lab-cultivated fats offer promise as replacements for ingredients tied to the label “bad and fat.” Chefs and food scientists are also finding ways to create indulgent textures and flavors without relying on trans or excessive saturated fats. These shifts are giving consumers more choices, making it easier to avoid asking repeatedly whether is trans fat good or bad—because it’s simply being removed altogether. Looking forward, continued advocacy, technological advancement, and education will shape a healthier and more transparent food environment.

Conclusion: Understanding What’s Worse—Trans Fat or Saturated Fats—Empowers Better Choices

In the ongoing debate about dietary fats, it’s clear that not all fats are created equal. When considering what’s worse, trans fat or saturated fats, the scientific consensus is unequivocal on trans fats being the more dangerous of the two. Their impact on cardiovascular health, systemic inflammation, and metabolic function makes them a uniquely harmful component of the modern diet. Understanding why trans fats are bad for you and recognizing how they hide in everyday foods empowers consumers to make better decisions that support long-term well-being.

Saturated fats, while still worthy of caution, require a more contextual approach. They may be included in a health-supportive diet if consumed in moderation and derived from quality sources. However, the shift toward plant-based fats and whole foods provides a safer and often more nutritious pathway for those looking to avoid what kinds of products are commonly called bad.

By staying informed, reading labels carefully, and asking critical questions like “is trans fat good for anything?” or “how much saturated fat is too much?,” individuals can navigate the food environment with greater confidence and clarity. In a world where nutrition information is often contradictory and overwhelming, distinguishing between bad and fat that might not be as bad after all is a crucial step toward better health.

Further Reading:

The Skinny on Dietary Fats: The Best and Worst for Your Health