In the realm of cardiovascular health, high blood pressure—or hypertension—stands as one of the most prevalent and potentially dangerous conditions affecting millions worldwide. Traditionally, its causes are attributed to factors such as poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, genetics, and chronic stress. Yet, another variable often overlooked in clinical and public discourse is pain. Can pain cause high blood pressure? Or more specifically, does pain raise blood pressure in a measurable and clinically relevant way? These are not just theoretical queries; they lie at the intersection of neurology, cardiology, and psychophysiology, presenting implications that are both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Pain is inherently subjective, yet its physiological consequences are anything but. The body’s response to acute or chronic discomfort sets off a cascade of hormonal, neurological, and cardiovascular reactions. This complex interplay can lead to temporary spikes or even sustained elevations in blood pressure. When considering whether pain affects blood pressure, it is essential to examine not only the biological mechanisms behind this association but also the conditions under which pain may transition from a temporary trigger to a chronic hypertensive risk factor.

In this comprehensive article, we delve into the science of how and why pain influences blood pressure, exploring both acute and chronic pain scenarios, the mediating role of the nervous system, and the potential for high blood pressure due to pain to become a serious health concern. We will also consider clinical case studies, examine treatment implications, and discuss preventative strategies that address both cardiovascular and pain-related conditions simultaneously.

You may also like: Sudden Spikes in Blood Pressure: What Can Cause a Sudden Increase and When to Seek Medical Attention

The Physiology of Pain and Its Relationship with Blood Pressure

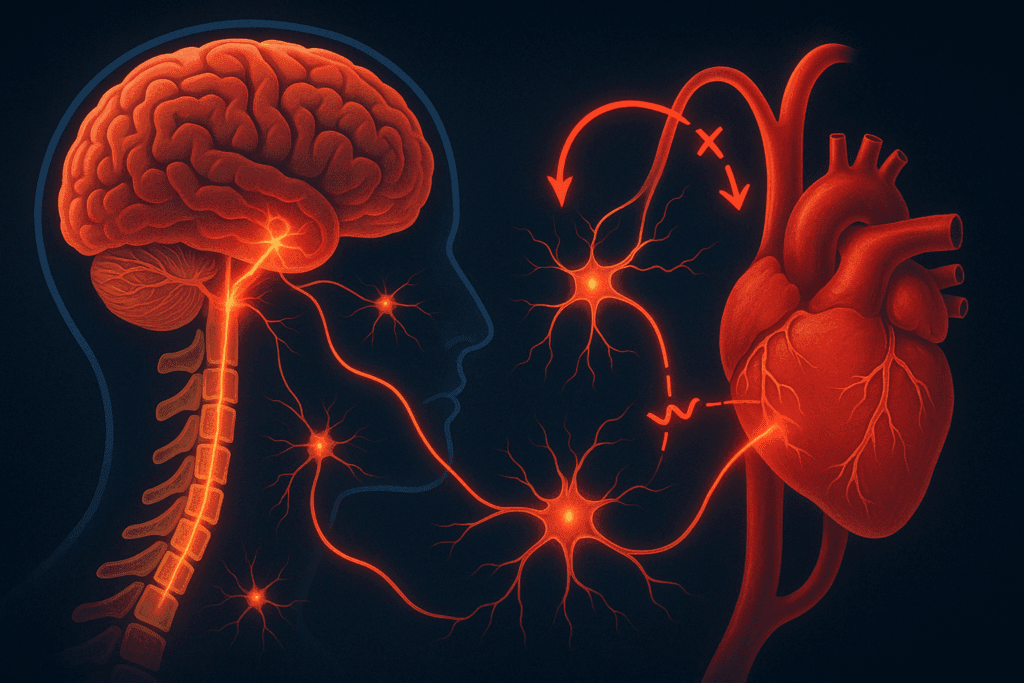

To understand whether pain can cause high blood pressure, we must begin with the physiology of pain itself. Pain acts as an alert system, signaling that something is wrong in the body. This warning is not just perceived mentally—it activates the autonomic nervous system, particularly the sympathetic branch. The sympathetic nervous system is responsible for the ‘fight or flight’ response, and its activation leads to the release of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. These hormones prepare the body for action by increasing heart rate, constricting blood vessels, and consequently raising blood pressure.

This response is adaptive in the short term. For instance, if you stub your toe or experience a minor injury, your body reacts swiftly to prevent further damage. However, repeated or chronic activation of this stress system due to ongoing pain can have deleterious effects. It is under these circumstances that we begin to see a more sustained impact—one where pain increases blood pressure in ways that may contribute to long-term cardiovascular risk.

Numerous studies have confirmed that both acute and chronic pain can affect cardiovascular parameters. For example, patients undergoing painful medical procedures without adequate analgesia have shown measurable increases in blood pressure. Similarly, individuals with conditions such as fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, or neuropathy often experience elevated BP levels compared to matched controls. These findings reinforce the conclusion that pain does not simply accompany high blood pressure; it may, in fact, be a causative or exacerbating factor.

Acute Pain and Temporary Blood Pressure Elevation

When someone experiences acute pain, such as that resulting from a burn, injury, or surgical procedure, the body reacts quickly. The initial pain signal travels through peripheral nerves to the spinal cord and then to the brain, where it is interpreted as discomfort. Almost simultaneously, the hypothalamus and adrenal glands are triggered to produce stress hormones. This results in peripheral vasoconstriction and increased cardiac output—two primary mechanisms by which pain can raise blood pressure.

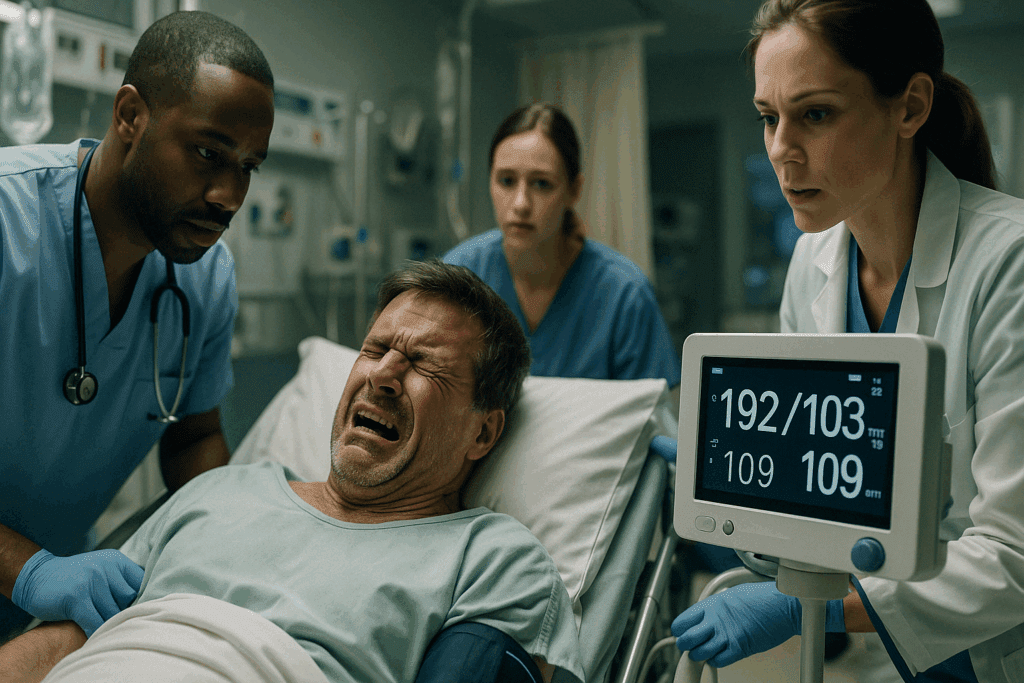

It is during this acute phase that the question—does pain cause blood pressure to rise?—can be most definitively answered in the affirmative. The rise is not only measurable but predictable. Emergency rooms and surgical suites often monitor blood pressure closely, not just for cardiovascular reasons, but because pain management can significantly influence BP readings. Anesthesia and analgesics are not merely comfort measures; they are also tools for cardiovascular stability.

Interestingly, even brief pain episodes, such as those experienced during dental procedures or blood draws, can elevate blood pressure temporarily. In individuals who are already hypertensive or who have other risk factors, this temporary elevation can tip the balance toward a hypertensive crisis, further underscoring the importance of adequate pain control as part of comprehensive medical care.

Chronic Pain as a Sustained Risk Factor for Hypertension

Chronic pain introduces a more complicated relationship with blood pressure. Unlike acute pain, which resolves within hours or days, chronic pain persists for weeks, months, or even years. This extended exposure to discomfort leads to long-term activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which may result in sustained elevations in blood pressure. Thus, when asking does pain increase blood pressure over time, the evidence points toward a significant and concerning trend.

One critical aspect of this relationship is the concept of allostatic load—the cumulative burden of chronic stress and physiological wear and tear on the body. Pain is a major contributor to this load, particularly when it is poorly managed or accompanied by sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. These factors create a feedback loop in which pain exacerbates hypertension, and vice versa. Over time, individuals with chronic pain may find their blood pressure difficult to control, even with medication.

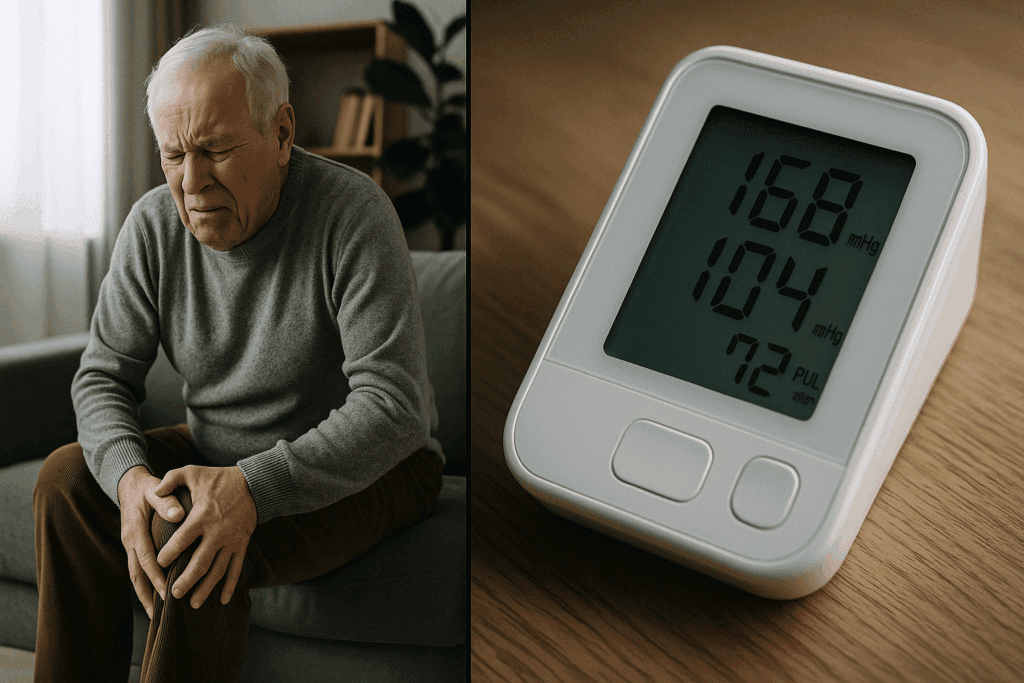

Moreover, certain populations are at higher risk. Older adults, who are more likely to experience degenerative conditions such as arthritis, often present with both chronic pain and hypertension. In such cases, it becomes essential to assess whether the pain is contributing to the difficulty in managing blood pressure. Similarly, people living with chronic pain syndromes, like complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), often exhibit elevated BP levels, suggesting that the link between chronic pain and cardiovascular risk is not merely coincidental.

The Role of the Nervous System in Mediating the Pain-Blood Pressure Connection

The nervous system plays a pivotal role in the relationship between discomfort and blood pressure. At the heart of this connection lies the baroreflex—a mechanism that helps regulate blood pressure via receptors in the blood vessels. When functioning properly, the baroreflex adjusts heart rate and vascular tone in response to changes in blood pressure. However, chronic pain can disrupt this regulatory system.

Emerging research suggests that chronic pain blunts baroreceptor sensitivity, meaning the body becomes less responsive to blood pressure fluctuations. This dysfunction may help explain why some individuals with chronic pain develop persistent hypertension. If the regulatory feedback loop is impaired, even minor stressors—including pain—can lead to significant cardiovascular responses. It also means that the body loses some of its capacity to return blood pressure to normal after a spike, resulting in sustained elevations.

Pain pathways and cardiovascular control share many overlapping structures in the brain, including areas such as the insular cortex, amygdala, and periaqueductal gray. These regions are involved in both pain perception and autonomic regulation. Consequently, chronic activation of these pathways may not only reinforce the experience of pain but also contribute to ongoing blood pressure dysregulation. This dual impact suggests that treating pain effectively could have meaningful benefits for cardiovascular health, not merely for quality of life.

Can Discomfort Cause High Blood Pressure? The Importance of Semantics and Perception

It is also worth exploring whether discomfort, as distinct from pain, can have similar cardiovascular effects. Discomfort is often described as a lower-intensity but persistent form of physical unease. While it may not activate the full fight-or-flight response in the way acute pain does, it still engages the stress response system to a lesser degree. Therefore, the question arises: can discomfort cause high blood pressure in a clinically significant way?

The answer is nuanced. Discomfort—such as that caused by gastrointestinal distress, musculoskeletal tension, or even emotional unease—can lead to mild increases in sympathetic activity. In people with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, even modest increases in sympathetic tone can contribute to elevated BP readings. While the spike may not be as dramatic as that seen with acute pain, the cumulative effect of prolonged discomfort can still be problematic.

This is particularly relevant in environments like intensive care units, where patients may not report severe pain but exhibit signs of persistent discomfort. In such settings, careful attention to comfort measures—including positioning, ambient noise control, and anxiety reduction—can have meaningful impacts on blood pressure control. Thus, while discomfort and pain are different in magnitude, they share enough physiological pathways to warrant joint consideration in hypertension management.

Clinical Case Studies and Real-World Implications

Several real-world scenarios underscore the clinical relevance of the pain-blood pressure connection. Consider a patient presenting to the emergency department with severe kidney stones. In the throes of acute pain, their blood pressure may spike to hypertensive crisis levels. Once adequate pain control is achieved—often with opioids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—blood pressure frequently returns to baseline without any antihypertensive intervention. This strongly supports the premise that pain caused the elevation.

In another case, an individual with poorly managed rheumatoid arthritis might present with sustained high blood pressure despite adherence to antihypertensive medication. Further investigation reveals that the patient experiences significant joint pain daily. Upon initiation of an effective pain management regimen—including physical therapy and anti-inflammatory agents—their blood pressure stabilizes, again reinforcing the role of chronic pain in contributing to sustained hypertension.

These examples illustrate that addressing pain is not merely a quality-of-life issue; it is an essential component of comprehensive cardiovascular care. Physicians should be trained to consider whether high blood pressure due to pain is a factor in difficult-to-manage cases. Integrative care models that include pain specialists, primary care physicians, and cardiologists may offer the most effective path forward for such patients.

Implications for Treatment and Preventative Care

Given the strong association between pain and blood pressure, it is critical to consider the therapeutic implications. First and foremost, clinicians should be aware of the cardiovascular impact of untreated or undertreated pain. In acute care settings, this may necessitate more aggressive pain management protocols to stabilize blood pressure. In chronic care scenarios, multimodal pain strategies—including medication, physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and alternative modalities like acupuncture—may help reduce both pain and hypertensive burden.

Medications used for pain control can also influence blood pressure. NSAIDs, for example, can contribute to elevated BP in some patients, especially when used chronically. Opioids, while effective for pain relief, carry risks of dependence and may cause hypotension in some cases. Thus, treatment plans must be carefully individualized, balancing the need for effective pain control with potential cardiovascular side effects.

Preventative strategies should also target the early recognition of pain-related hypertension. Routine pain assessments should be integrated into blood pressure monitoring protocols, especially for high-risk populations. Educating patients about the connection between pain and blood pressure empowers them to report symptoms more accurately, which can lead to earlier intervention and better outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions: The Connection Between Pain and Blood Pressure

1. Can short-term pain from injuries or dental procedures significantly raise blood pressure?

Yes, even brief episodes of pain—such as from a sprained ankle or a tooth extraction—can cause a noticeable increase in blood pressure. The body responds to acute pain with a surge of adrenaline, which tightens blood vessels and raises heart rate. This can result in temporary spikes in blood pressure that may be alarming, especially in individuals who already have hypertension. In some cases, clinicians have mistaken these spikes for unrelated hypertensive episodes, leading to unnecessary interventions. Therefore, understanding that pain can raise blood pressure in short bursts helps both patients and providers better interpret BP readings in context.

2. Does pain affect blood pressure differently depending on age or underlying health conditions?

Age and existing health conditions do play a role in how pain affects blood pressure. Older adults tend to have stiffer arteries, which are less able to accommodate pressure changes, making them more susceptible to sustained BP elevations from chronic pain. Additionally, individuals with metabolic disorders, kidney disease, or autoimmune conditions may experience more profound effects. For them, even moderate discomfort can cause high blood pressure that is more difficult to manage with standard medications. This interaction suggests the need for personalized treatment strategies when addressing both pain and blood pressure in older or medically complex populations.

3. Can emotional pain or psychological discomfort increase blood pressure the same way physical pain does?

While the mechanisms are not identical, emotional pain and psychological distress can have similar effects on blood pressure. Emotional stress activates the same sympathetic nervous system pathways that are triggered during physical pain. As a result, someone experiencing anxiety or grief may find their blood pressure temporarily elevated. Over time, repeated episodes of emotional discomfort can cause high blood pressure to become a chronic condition. This reveals the importance of addressing emotional well-being alongside physical health when considering whether discomfort can cause high blood pressure.

4. Are there any wearable technologies that can help detect blood pressure spikes due to pain?

Yes, there is a growing market for wearable technologies that track cardiovascular metrics in real time. Smartwatches and medical-grade monitors can detect fluctuations in heart rate and blood pressure during episodes of pain or stress. These tools can be particularly useful for patients who suspect that pain is increasing their blood pressure but lack concrete data. Advanced algorithms are being developed to distinguish pain-induced spikes from other causes, offering better diagnostic clarity. For those wondering, “does pain increase BP consistently?”—wearable devices may soon offer precise answers in real-world contexts.

5. Can pain medications normalize blood pressure if pain is the root cause of elevation?

In many cases, yes. When pain is directly contributing to elevated blood pressure, effective pain management can lead to normalization of BP levels. This is particularly true for acute pain scenarios such as post-operative recovery, where adequate analgesia often results in stable cardiovascular readings. However, not all pain medications are suitable for individuals with hypertension. For instance, NSAIDs can sometimes cause or worsen high blood pressure due to fluid retention. Thus, clinicians must weigh the benefits and risks carefully when selecting medications to treat both pain and elevated BP.

6. What role does sleep play in the relationship between pain and blood pressure?

Poor sleep quality can intensify both pain perception and blood pressure irregularities. Sleep deprivation increases sensitivity to pain and simultaneously activates the sympathetic nervous system, compounding cardiovascular strain. For individuals who suffer from chronic pain, disrupted sleep often leads to a cycle in which pain causes high blood pressure, which in turn further disrupts sleep. Addressing sleep disorders or adopting better sleep hygiene may help reduce both pain and the frequency with which pain causes blood pressure to rise. This insight highlights the interconnected nature of lifestyle, sleep, and cardiovascular health.

7. Does pain cause blood pressure to rise during routine medical exams, and how should this be handled?

Yes, it’s not uncommon for patients experiencing discomfort during routine exams—such as from cold instruments, blood draws, or muscle strain while sitting—to show temporarily elevated blood pressure. This phenomenon, sometimes mistaken for white coat hypertension, suggests that pain causes blood pressure to rise even in clinical settings that may otherwise seem benign. Medical professionals should consider these variables when interpreting single high BP readings and ideally measure blood pressure after a period of rest or once discomfort is addressed. In some clinics, pre-measurement relaxation techniques are now being used to reduce the impact of incidental pain on BP readings.

8. Can chronic inflammation linked to pain contribute to long-term hypertension?

Chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a key mediator in the development of hypertension. Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia, which involve persistent pain and systemic inflammation, have been associated with elevated blood pressure over time. Inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein and interleukins can impair endothelial function, leading to vascular rigidity. When chronic pain drives this inflammatory state, the answer to “does pain increase blood pressure in the long run?” becomes a definitive yes. Targeting inflammation through diet, exercise, and medical therapy may reduce both pain and the risk of chronic hypertension.

9. How can patients advocate for themselves if they suspect high blood pressure due to pain is being overlooked?

Patients can take an active role by keeping a symptom diary that tracks instances when pain coincides with elevated blood pressure readings. They should communicate openly with their healthcare providers, emphasizing any patterns they’ve observed. Mentioning that they believe pain affects blood pressure may prompt more targeted investigations or referrals to pain management specialists. Additionally, seeking second opinions from clinicians who specialize in integrative medicine may yield broader treatment options. Self-advocacy is especially important when standard antihypertensive treatments fail and there’s a suspicion that unaddressed pain may be the underlying cause.

10. Could future treatment guidelines include pain management as a standard component of hypertension care?

There is growing recognition in the medical community that pain and blood pressure should not be treated in isolation. Future hypertension guidelines may well incorporate pain assessment tools and interdisciplinary strategies as part of standard care. Pilot programs in several hospital systems are already integrating pain specialists into cardiovascular clinics to better manage patients with dual diagnoses. As research continues to show that pain can cause high BP and that untreated discomfort raises blood pressure, such integrations are likely to become more mainstream. Including pain management in hypertensive protocols could ultimately improve both patient outcomes and healthcare efficiency.

Final Thoughts: Reflecting on How Pain Can Cause Blood Pressure to Rise and Why It Matters

Understanding the connection between pain and blood pressure is more than a clinical curiosity—it is a public health imperative. As the evidence continues to accumulate, it becomes increasingly clear that pain is not merely a symptom to be endured or suppressed but a physiological event with far-reaching consequences. Does pain elevate blood pressure? Without question, in both acute and chronic forms. Can pain cause high BP that resists traditional treatment? Yes, especially when pain is persistent and unmanaged.

By acknowledging the multifaceted ways in which pain affects blood pressure, healthcare professionals can adopt a more integrated approach to cardiovascular care. Whether through improved pain assessment, expanded therapeutic options, or greater interdisciplinary collaboration, addressing pain as a contributor to hypertension opens the door to more effective treatment pathways. The question is no longer whether pain can raise blood pressure—but what we are prepared to do about it.

Ultimately, managing hypertension may require more than antihypertensive drugs and lifestyle modifications. It may require us to listen more closely to our patients’ experiences of pain and discomfort, recognizing these not just as isolated complaints but as central players in the cardiovascular narrative.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Can Pain Cause High Blood Pressure?