Regurgitation, the backward flow of food or liquid from the stomach into the mouth without nausea or the effort of vomiting, is more than just a temporary inconvenience. For many, it is an unexpected and recurring issue that disrupts daily life and diminishes overall digestive comfort. Understanding what causes regurgitation can offer critical insights not only into gastrointestinal health but also into a host of seemingly unrelated lifestyle and health factors. While occasional regurgitation may be benign, persistent episodes can signal underlying conditions that warrant closer attention and care. In this comprehensive exploration, we uncover the less obvious reasons behind regurgitation, the symptoms that accompany it, and when to seek medical evaluation. We also examine the connection between related symptoms such as burping up food and that uncomfortable sensation when food comes up during a burp, all of which are vital for a clear picture of digestive wellness.

You may also like: How Long Does GERD Last in Adults? Expert Insights on This Common Yet Persistent Digestive Condition

Understanding Regurgitation: More Than Just a Digestive Quirk

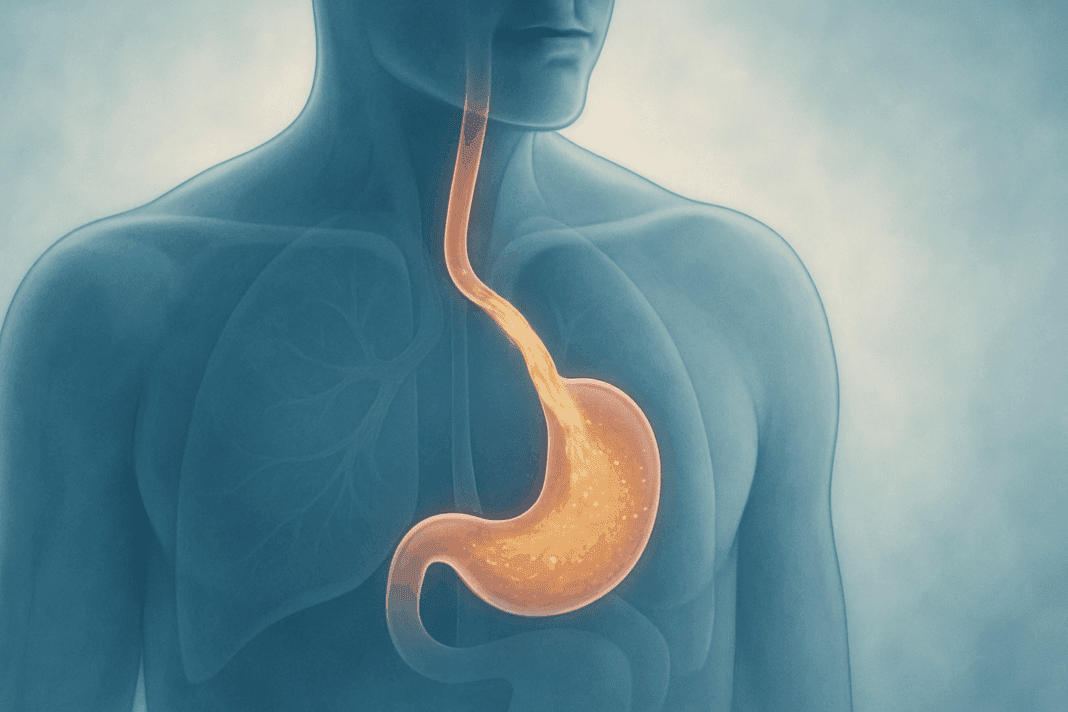

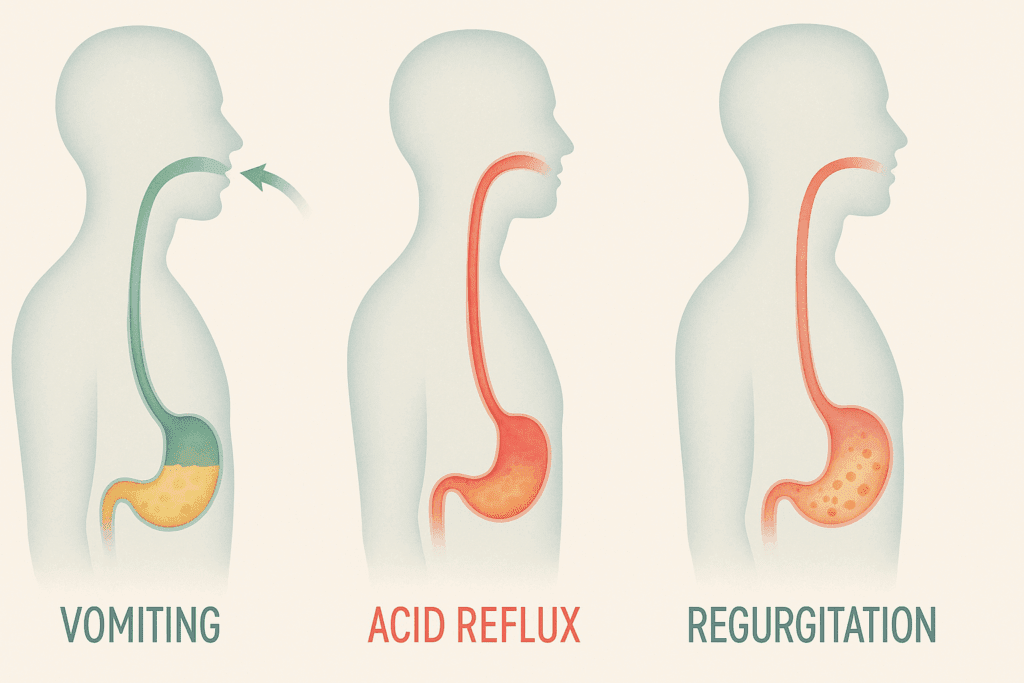

To understand regurgitation, it’s helpful to differentiate it from similar gastrointestinal events such as vomiting or acid reflux. Regurgitation typically involves the effortless return of undigested or partially digested food into the throat or mouth. It is not accompanied by retching or nausea, distinguishing it from vomiting. Nor is it always associated with the burning sensation typical of acid reflux, although the two often coexist. For many people, regurgitation is a misunderstood symptom that can cause confusion and delay proper diagnosis.

One common misconception is that regurgitation is simply another form of “heartburn.” While regurgitation can be a symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), it also arises independently of acid. For example, regurgitated food may taste undigested, and episodes may occur without any acidic aftertaste. This subtlety is important for clinical distinction and guides treatment strategies. In cases where individuals report that food comes up when they burp, the issue might not be acid-related at all, but rather mechanical or behavioral in origin.

Clinicians often consider regurgitation part of a broader constellation of upper gastrointestinal symptoms, which include bloating, early satiety, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), and the sensation of food “sticking” in the chest. When patients describe burping up food or experiencing regurgitation during everyday activities like talking or bending over, it suggests a dysfunction in the esophageal sphincters or muscular coordination of the digestive tract. Knowing the underlying cause of these episodes is essential for developing an effective and personalized treatment plan.

What Causes Regurgitation? Exploring Common and Overlooked Factors

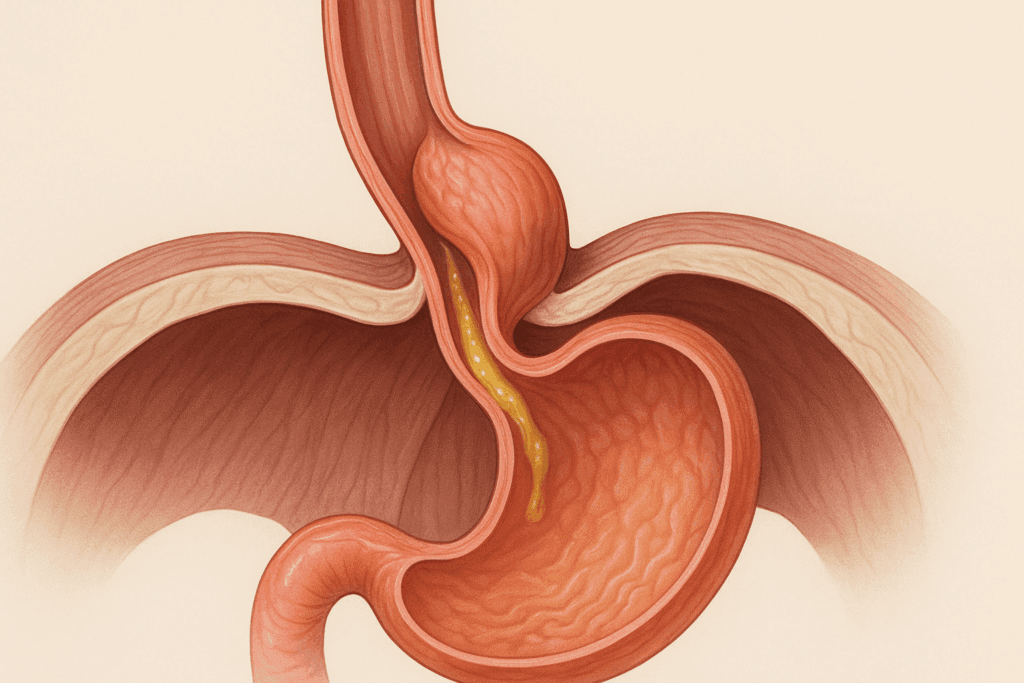

The causes of regurgitation are surprisingly diverse, ranging from structural abnormalities to behavioral patterns and even psychological triggers. Among the most common culprits is a weakened lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the muscular valve separating the esophagus from the stomach. When this valve fails to close properly, gastric contents can move upward, resulting in regurgitation. This dysfunction often overlaps with GERD, but it may also occur independently in conditions like hiatal hernia or achalasia.

Hiatal hernia, where part of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm into the chest cavity, frequently contributes to LES dysfunction. The displacement alters pressure dynamics, making it easier for stomach contents to escape upward. Similarly, esophageal motility disorders—such as achalasia or diffuse esophageal spasm—impair the rhythmic contractions that normally move food toward the stomach. Instead, food can linger in the esophagus and later resurface with minimal provocation.

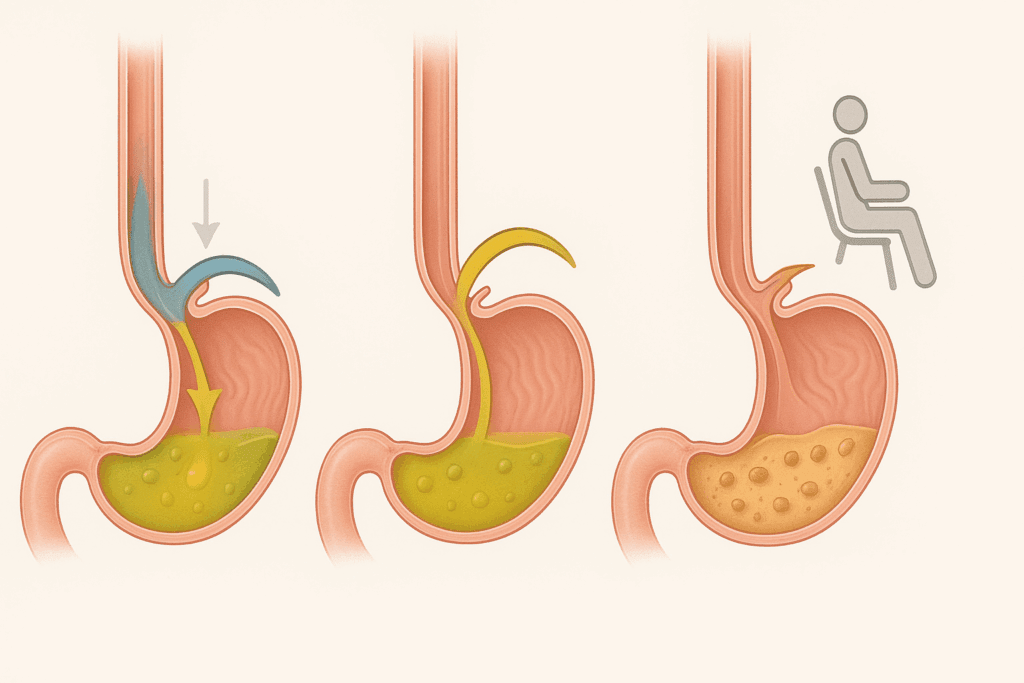

Diet and eating habits also play a significant role in what causes regurgitation. Large meals, high-fat foods, and frequent consumption of carbonated beverages increase gastric pressure and delay stomach emptying, thereby promoting regurgitation. Additionally, certain behaviors—such as lying down immediately after eating or engaging in vigorous activity—can trigger episodes. Individuals who habitually eat quickly or skip chewing properly often introduce excess air and strain into the digestive system, which may lead to symptoms like food coming up when they burp.

Importantly, medications can also influence digestive tract function and contribute to regurgitation. Calcium channel blockers, anticholinergics, and some sedatives relax the LES, increasing the likelihood of upward food movement. In patients using multiple medications, particularly older adults, polypharmacy becomes a risk factor worth evaluating. Understanding these nuances is vital for accurate diagnosis and long-term relief.

When I Burp, Food Comes Up: Recognizing Functional and Behavioral Causes

For many people, the sensation that “when I burp food comes up” is more than just a rare nuisance—it’s a recurring phenomenon that feels intrusive and confusing. This specific experience is often tied to a functional digestive disorder rather than a purely anatomical one. For example, rumination syndrome, a condition characterized by the repetitive regurgitation of recently ingested food, typically occurs within minutes of eating and involves voluntary contraction of the abdominal muscles. Unlike GERD, it is not associated with acid reflux but rather with a learned behavior that becomes habitual over time.

Rumination is surprisingly common in both children and adults and often goes unrecognized because patients may not realize they are voluntarily engaging the abdominal muscles that facilitate regurgitation. The condition is frequently misdiagnosed as persistent GERD, leading to ineffective treatments with acid suppressants rather than behavioral interventions such as diaphragmatic breathing or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Another behavioral factor involves supragastric belching, where air is swallowed and then rapidly expelled without reaching the stomach. This process differs from true gastric belching and can contribute to the sensation of food rising in the throat. Individuals may inadvertently swallow air while eating, talking, or even during periods of anxiety, creating a cycle that perpetuates discomfort and regurgitation-like symptoms.

In both cases, the presence of food coming up when I burp may not reflect a structural digestive disorder but rather a complex interaction between behavior, physiology, and sometimes emotional health. Recognizing the behavioral underpinnings of regurgitation empowers patients and clinicians to pursue more targeted and effective therapies beyond the traditional scope of acid suppression or dietary modification.

Burping Up Food: Differentiating Between Normal and Abnormal Digestive Events

While occasional burping is a normal response to swallowing air during meals, burping up food is a different matter entirely. This symptom suggests that the esophageal barrier is not functioning optimally and that gastric contents are being pushed upward along with expelled air. Although sometimes linked to overeating or consuming fizzy drinks, persistent or frequent episodes indicate a more serious issue that requires medical evaluation.

Conditions such as gastroparesis, where the stomach empties more slowly than normal, can result in the retention of food and increased pressure that promotes regurgitation during burping. Gastroparesis is particularly common among individuals with diabetes, but it can also result from viral infections, post-surgical nerve damage, or idiopathic causes. As pressure builds in the stomach, the path of least resistance may be upward through a compromised LES, leading to both belching and regurgitation of food.

Similarly, esophageal strictures or narrowing due to scarring from chronic acid exposure or eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) can trap food in the esophagus. When trapped contents are expelled, they may be mistaken for routine burping but are actually a sign of impaired transit and mechanical obstruction. These structural anomalies often require diagnostic endoscopy and sometimes dilation procedures for symptom relief.

Even subtle anatomical variations, like Schatzki rings—thin mucosal structures in the lower esophagus—can create intermittent obstructions that make swallowing difficult and increase the likelihood of regurgitation during belching. Understanding the anatomical and motility-related contributors to burping up food allows for a more refined diagnostic process and the selection of appropriate medical, dietary, or procedural interventions.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) and Its Relationship to What Causes Regurgitation

One of the most well-established explanations for what causes regurgitation is GERD, a condition in which stomach acid or contents flow back into the esophagus due to a weakened LES. GERD affects millions of people worldwide and remains one of the leading reasons for medical visits related to digestive health. While heartburn is its hallmark symptom, regurgitation is another key feature that often goes underappreciated.

In GERD-related regurgitation, the acidic contents of the stomach may rise up to the esophagus and even the mouth, leaving a sour or bitter taste. This can occur particularly when lying down, bending over, or following large meals. Chronic exposure of the esophageal lining to acid can lead to complications such as esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, or even esophageal cancer in long-standing cases.

However, GERD is not always acid-related. Non-acid reflux, which involves bile or other non-acidic substances, can also result in regurgitation and is not always responsive to traditional proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). In such cases, diagnostic tools like impedance-pH monitoring are essential for detecting the presence and nature of reflux episodes, ensuring that treatment is tailored accordingly.

Treatment of GERD-related regurgitation often includes lifestyle modifications, such as elevating the head of the bed, weight loss, and dietary changes. Avoiding trigger foods—like caffeine, chocolate, alcohol, and high-fat meals—can substantially reduce symptoms. In more severe cases, medical or surgical interventions like fundoplication may be necessary to reinforce the LES and restore normal function. Understanding the link between GERD and regurgitation provides a solid foundation for managing this symptom, but it is equally important to recognize that not all regurgitation stems from GERD.

What Causes Regurgitation in Healthy Individuals? Temporary Triggers and Everyday Habits

While chronic regurgitation is often rooted in underlying pathology, even healthy individuals may experience occasional regurgitation due to transient factors. These include overeating, consuming gas-producing foods, or engaging in strenuous physical activity immediately after meals. Large meals distend the stomach and can overcome the pressure barrier of the LES, particularly when the body is in a reclined or compressed posture.

Foods such as beans, cruciferous vegetables, carbonated beverages, and chewing gum introduce air or increase fermentation in the digestive tract, enhancing intra-abdominal pressure and promoting regurgitation. Additionally, swallowing air while talking, eating too fast, or drinking through straws can introduce aerophagia, which may manifest as the sensation that food comes up when you burp.

Alcohol and tobacco use are other important considerations. Both substances relax the LES, thereby increasing susceptibility to regurgitation. Alcohol, in particular, also delays gastric emptying and increases stomach acidity, further amplifying the conditions conducive to regurgitation. Caffeine-containing drinks may similarly contribute to LES relaxation, especially when consumed in large quantities or on an empty stomach.

These lifestyle-related causes are often reversible with behavioral adjustments. Educating patients about meal timing, portion control, and posture can significantly reduce the frequency and intensity of regurgitation episodes. Moreover, identifying and eliminating specific dietary triggers through a food diary or elimination trial can empower individuals to take control of their symptoms without necessarily requiring medication.

Hidden Medical Conditions That Can Explain What Causes Regurgitation

Beyond the more common causes, there are several lesser-known medical conditions that may be responsible for regurgitation. One such condition is laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), often referred to as “silent reflux,” because it lacks the classic symptoms of heartburn. Instead, LPR presents with chronic throat clearing, hoarseness, cough, or the sensation of a lump in the throat, alongside regurgitation. Because these symptoms overlap with those of allergies or respiratory illness, LPR is often underdiagnosed.

Neurological disorders also play a significant role in esophageal function. Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke can all impair the neural coordination required for smooth swallowing and digestion. When muscle tone or reflex timing is disrupted, regurgitation can result even without anatomical defects. These cases highlight the importance of a comprehensive medical history and neurological examination in patients presenting with unexplained regurgitation.

Connective tissue disorders like scleroderma can lead to esophageal dysmotility and LES dysfunction, creating a predisposition to both GERD and regurgitation. Similarly, endocrine conditions such as hypothyroidism may slow overall gastrointestinal transit, increasing the likelihood of food retention and regurgitation. In such scenarios, addressing the underlying systemic disease often leads to improvement in digestive symptoms as well.

The diagnostic approach to regurgitation must therefore remain broad, integrating gastrointestinal, neurological, musculoskeletal, and behavioral assessments. By considering a wide range of potential contributors, clinicians can provide more personalized and effective care, helping patients achieve lasting relief from this troubling symptom.

When to Seek Medical Attention for Regurgitation: Warning Signs and Diagnostic Approaches

Although occasional regurgitation may be harmless and self-limiting, persistent or worsening symptoms warrant medical evaluation, particularly when they are accompanied by other red flags. If regurgitation becomes frequent—occurring several times a week or interfering with daily activities—it may indicate an underlying disorder that requires treatment. Warning signs that should prompt immediate attention include unintentional weight loss, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), chest pain not related to exertion, chronic coughing, and the regurgitation of blood or material resembling coffee grounds, which may suggest gastrointestinal bleeding.

Another concern is when individuals report that food coming up when they burp has become a daily occurrence, especially if it is accompanied by foul taste, choking, or nighttime episodes that disturb sleep. These presentations may indicate a combination of GERD, LPR, or a structural anomaly such as a stricture or diverticulum. In such cases, an upper endoscopy is often the first step in evaluating the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum for signs of inflammation, obstruction, or abnormal anatomy.

In more complex cases, additional diagnostic tools may be necessary. Esophageal manometry assesses the strength and coordination of esophageal muscle contractions, which can reveal disorders like achalasia or ineffective motility. Ambulatory pH monitoring evaluates the frequency and acidity of reflux episodes over 24 hours, providing objective data that helps differentiate between acid and non-acid reflux. Impedance monitoring, often done in conjunction with pH testing, can detect non-acidic substances that may be contributing to regurgitation.

For those experiencing regurgitation without clear anatomic or acid-related causes, testing for motility disorders or rumination syndrome becomes essential. In pediatric populations and individuals with developmental disabilities, regurgitation may present atypically, further complicating diagnosis. In such populations, behavioral observation and multidisciplinary assessment may offer the clearest path to treatment. Ultimately, timely recognition and evaluation of concerning symptoms can prevent complications and ensure appropriate, individualized therapy.

Treatment Strategies for Regurgitation: From Lifestyle Adjustments to Advanced Therapies

Once the cause of regurgitation is identified, treatment can be customized to address the specific factors involved. For many patients, lifestyle modifications form the cornerstone of management. These may include eating smaller meals, avoiding lying down after eating, reducing intake of trigger foods, and elevating the head of the bed to prevent nighttime regurgitation. Keeping a food diary to track symptoms can help identify personal triggers and empower individuals to make informed dietary choices.

Medications are often introduced when lifestyle changes alone are insufficient. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2-receptor antagonists are commonly prescribed for acid-related regurgitation, especially when GERD is suspected. However, in cases of non-acid regurgitation or rumination syndrome, these medications may have limited utility. Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide or domperidone may be useful for promoting gastric emptying in individuals with gastroparesis.

Behavioral therapies are particularly effective for functional and habit-based conditions like rumination syndrome and supragastric belching. Diaphragmatic breathing techniques, biofeedback, and cognitive-behavioral therapy can retrain abdominal and respiratory muscles, reducing the frequency and severity of regurgitation episodes. These strategies are especially beneficial for patients who notice that food comes up when they burp without associated acid symptoms or anatomical issues.

In severe or refractory cases, procedural or surgical interventions may be considered. Endoscopic procedures like Stretta therapy or transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) aim to improve LES function without traditional surgery. For more advanced cases, Nissen fundoplication—a surgical procedure that reinforces the LES using the upper part of the stomach—offers durable relief for many patients with GERD-related regurgitation. Selection of surgical candidates depends on careful diagnostic evaluation and exclusion of motility disorders that could worsen after intervention.

Personalized treatment that reflects the individual’s specific physiological, anatomical, and behavioral contributors to regurgitation is key. A multidisciplinary approach that includes gastroenterologists, dietitians, behavioral health specialists, and, when appropriate, surgeons, can offer comprehensive care and long-term symptom resolution.

Living With Chronic Regurgitation: Coping Strategies and Quality of Life Considerations

Chronic regurgitation can significantly impact quality of life, affecting eating habits, social interactions, sleep, and even mental health. For many, the unpredictability of symptoms adds a layer of anxiety that compounds the physical discomfort. Individuals often report self-consciousness during meals or social outings, fearing the embarrassment of food or liquid unexpectedly coming back up. Over time, this anxiety may lead to food avoidance, weight loss, or nutritional deficiencies.

Mental health support plays an essential role in managing the psychosocial burden of regurgitation. For those experiencing conditions like rumination syndrome or supragastric belching, the mind-body connection is particularly strong. Psychological interventions not only reduce symptoms but also help individuals regain a sense of control and agency over their health. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), meditation, and relaxation techniques can mitigate physiological responses that exacerbate regurgitation.

Nutritional counseling can also improve outcomes for individuals struggling to maintain a balanced diet. Registered dietitians can recommend foods that are easier to digest, less likely to cause gas, and less prone to triggering regurgitation. This often includes low-fat, non-spicy meals with adequate hydration and fiber. Texture modifications, such as choosing softer or blended foods, may be beneficial for those with coexisting swallowing difficulties or esophageal narrowing.

Incorporating gentle physical activity, such as walking after meals or engaging in yoga poses that promote digestion, may enhance gastrointestinal motility. However, individuals should avoid intense workouts immediately after eating, as these can exacerbate symptoms. Sleep hygiene is another important consideration. Elevating the head of the bed and avoiding meals two to three hours before bedtime can minimize nocturnal regurgitation and improve sleep quality.

Ultimately, adapting to chronic regurgitation involves a combination of symptom management, emotional resilience, and practical lifestyle strategies. With the right support and medical guidance, individuals can reduce the burden of their symptoms and live more comfortably and confidently.

Burping Up Food and Its Overlap With Other Digestive Disorders

When individuals describe the experience of burping up food, they may unknowingly be pointing to a broader spectrum of digestive dysfunction. This symptom overlaps with several gastrointestinal conditions that require differential diagnosis. For example, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), an allergic inflammatory condition of the esophagus, often presents with food impaction, chest discomfort, and regurgitation. EoE is frequently mistaken for GERD but responds differently to treatment, typically requiring dietary changes and corticosteroids.

Similarly, Zenker’s diverticulum—a pouch that forms at the junction of the pharynx and esophagus—can trap food particles and lead to delayed regurgitation long after eating. This structural anomaly typically affects older adults and is associated with chronic coughing, aspiration, and halitosis. Diagnosis often involves a barium swallow study, and treatment may require endoscopic or surgical repair.

Functional dyspepsia, a common upper gastrointestinal disorder characterized by bloating, early satiety, and upper abdominal discomfort, also overlaps with symptoms like burping and regurgitation. Unlike GERD, functional dyspepsia is not associated with acid exposure and may be more responsive to dietary and psychological interventions. Understanding these nuanced distinctions enables clinicians to guide patients toward more accurate diagnoses and tailored therapies.

Even irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), although traditionally associated with lower gastrointestinal symptoms, may include upper GI manifestations such as nausea, bloating, and occasional regurgitation. This underscores the importance of taking a holistic view of digestive health, recognizing that symptoms are often interconnected and may not fit neatly into one diagnostic category.

By paying attention to the full context of a patient’s symptoms, including when food comes up during a burp or whether regurgitation is tied to specific foods or activities, healthcare providers can more effectively distinguish between overlapping conditions and avoid misdiagnosis. This comprehensive approach promotes more effective and sustainable symptom relief.

Dietary and Nutritional Factors That Influence What Causes Regurgitation

Nutrition plays a pivotal role in both the onset and management of regurgitation. Certain foods are well-known triggers, especially those high in fat, caffeine, or acidity. Chocolate, citrus fruits, tomatoes, spicy dishes, and peppermint are frequent culprits that lower LES pressure or irritate the esophageal lining. However, beyond these common offenders, individual sensitivities vary widely, highlighting the importance of personalized dietary guidance.

High-fat meals delay gastric emptying, increasing the volume and pressure in the stomach and making regurgitation more likely. Meals rich in oil, butter, cheese, or creamy sauces often exacerbate symptoms, particularly when consumed in large quantities or late in the day. Similarly, carbonated beverages introduce gas into the digestive tract, raising intra-abdominal pressure and prompting belching and potential food regurgitation.

Fiber, while essential for digestive health, can also produce gas and bloating in some individuals, especially if introduced too quickly or consumed in insoluble forms. Balancing fiber intake with adequate hydration and gradually increasing fiber-rich foods allows the gut to adjust and minimizes discomfort. Soluble fibers, such as those found in oats, bananas, and carrots, are generally more soothing to the gastrointestinal tract.

Meal timing and structure also influence regurgitation risk. Skipping meals or eating too quickly can disrupt normal digestive rhythms and increase air swallowing. Small, frequent meals spaced evenly throughout the day help maintain stable digestion and prevent overloading the stomach. Chewing food thoroughly and avoiding conversation while eating can further reduce air intake and regurgitation likelihood.

For individuals who experience food coming up when they burp, especially after specific meals, keeping a symptom diary can be a powerful tool. By tracking what was eaten, when symptoms occurred, and any contextual factors (such as stress or posture), patterns often emerge that guide dietary refinement. Working with a dietitian to implement elimination or low-FODMAP diets can be particularly effective for identifying hidden sensitivities and achieving symptom control.

Looking Ahead: Advances in Understanding and Managing Regurgitation

Medical science continues to evolve in its understanding of gastrointestinal function, and regurgitation is no exception. Research into the gut-brain axis has revealed how closely digestive symptoms are tied to emotional and neurological processes. This growing body of knowledge supports a more integrative model of care, one that recognizes the interplay of physical, psychological, and environmental factors.

Technological advancements also offer new possibilities for diagnosis and treatment. High-resolution manometry, for example, provides more precise data on esophageal motility patterns than traditional methods. Similarly, impedance-pH monitoring has improved the ability to detect non-acidic reflux, expanding the diagnostic landscape for individuals with regurgitation but no heartburn. Emerging treatments such as electrical stimulation of the LES and magnetic sphincter augmentation hold promise for those with refractory symptoms.

On the behavioral front, digital health tools and mobile apps now allow patients to log meals, symptoms, and stress levels in real-time, facilitating better self-awareness and clinician-patient communication. Virtual therapy platforms also increase access to psychological support for conditions like rumination syndrome, where behavioral intervention is central to treatment.

Ultimately, the future of regurgitation management lies in personalization. As we move away from one-size-fits-all approaches and toward individualized care informed by comprehensive assessment, patients stand to benefit from more accurate diagnoses, effective treatments, and improved quality of life. Continued research, interdisciplinary collaboration, and patient education will be vital in advancing care and reducing the burden of this often-overlooked symptom.

Frequently Asked Questions About Regurgitation, Burping Up Food, and Related Digestive Symptoms

Can regurgitation be influenced by stress or emotional triggers?

Yes, emotional and psychological factors can significantly influence regurgitation, especially in cases that aren’t linked to structural gastrointestinal issues. Chronic stress and anxiety can lead to heightened muscle tension and altered gut-brain signaling, which disrupt normal esophageal motility and swallowing coordination. This dysfunction often manifests in individuals who notice that food comes up when they burp during stressful situations. Moreover, anxiety can exacerbate air swallowing (aerophagia), which increases gastric pressure and makes regurgitation more likely. Incorporating stress-reducing practices such as deep breathing, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or even guided mindfulness can offer meaningful relief for those whose symptoms are tied to emotional triggers.

Why does burping up food happen hours after eating?

Burping up food hours after eating may suggest delayed gastric emptying, also known as gastroparesis, or a persistent esophageal motility issue. In these scenarios, the digestive process slows down, allowing food to remain in the stomach or esophagus longer than usual. This residual content can be expelled when intra-abdominal pressure increases, such as during a burp or positional change. People often experience this delayed regurgitation after large meals, especially when lying flat or engaging in sudden movements. If you consistently notice food coming up when you burp well after mealtime, it’s important to consult a gastroenterologist for further evaluation and to consider testing for underlying conditions such as diabetes-related neuropathy or functional dyspepsia.

How does posture impact regurgitation and burping up food?

Posture plays a surprisingly powerful role in managing or triggering regurgitation symptoms. Sitting or lying down after eating can reduce the effect of gravity, making it easier for gastric contents to flow back into the esophagus. This is particularly true for individuals who report that when they burp, food comes up shortly afterward. On the other hand, maintaining an upright position for at least 30 to 60 minutes after eating allows for more efficient gastric emptying and reduces pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter. Elevating the head of the bed by 6 to 8 inches can also prevent nighttime regurgitation episodes. For those with sedentary routines, incorporating short walks after meals may not only help digestion but also decrease the frequency of regurgitation events.

What causes regurgitation during exercise or physical exertion?

When discussing what causes regurgitation during physical activity, intra-abdominal pressure becomes a central factor. Exercises that involve bending, straining, or sudden jolts—like crunches, running, or weightlifting—can temporarily overcome the barrier created by the lower esophageal sphincter. This leads to gastric contents rising, especially in people who’ve eaten recently. Those who experience food coming up when they burp during or after workouts may benefit from modifying their exercise timing and intensity. Waiting at least two hours after eating before engaging in physical activity and avoiding core-compression movements can significantly reduce symptoms. Additionally, high-impact workouts may be swapped for gentler options like swimming or brisk walking to minimize regurgitation risk while maintaining fitness goals.

Could certain medications be behind why food comes up when I burp?

Yes, some prescription and over-the-counter medications can weaken the esophageal sphincter or affect gastric motility, both of which contribute to regurgitation. Common culprits include calcium channel blockers, used for blood pressure management; benzodiazepines, prescribed for anxiety; and anticholinergic agents found in many cold and allergy remedies. These medications can cause side effects like increased reflux or even functional changes in the esophagus, leading to scenarios where burping up food becomes more frequent. If you’ve recently started a new medication and noticed that when you burp food comes up more often, it’s worth discussing with your healthcare provider. They may recommend alternative treatments or adjust dosages to minimize gastrointestinal side effects.

Is there a link between food intolerances and burping up food?

Emerging evidence suggests that certain food intolerances—especially those involving fermentable carbohydrates like those found in the FODMAP group—may contribute to regurgitation and other upper GI symptoms. These poorly absorbed sugars ferment in the gut, producing gas and pressure that can lead to burping and even food coming back up when pressure exceeds sphincter resistance. People with lactose intolerance, for instance, may unknowingly exacerbate regurgitation by consuming dairy products that their digestive systems can’t properly process. Similarly, gluten sensitivity or fructose malabsorption may play a role in some cases. Keeping a food and symptom journal is a practical way to detect these patterns and tailor your diet accordingly, potentially reducing regurgitation episodes without medication.

What causes regurgitation to happen at night and disrupt sleep?

Nocturnal regurgitation is often triggered by lying down too soon after eating, which removes the gravitational assistance that typically helps keep stomach contents in place. When individuals experience symptoms such as burping up food or waking with a sour taste in their mouths, it may be due to nighttime reflux episodes. People with conditions like sleep apnea may also face compounded risks, as disrupted breathing can increase thoracic pressure and affect digestive mechanics. Using wedge pillows, raising the head of the bed, and eating earlier in the evening are common solutions. Additionally, avoiding alcohol and heavy meals before bedtime can help reduce the likelihood of regurgitation disturbing your sleep cycle.

How do gender and age influence what causes regurgitation?

While regurgitation can affect people of all ages and genders, its causes and presentation may vary across demographics. Older adults, for instance, are more likely to have age-related weakening of the lower esophageal sphincter or to be on medications that influence gastric function. They may also present with atypical symptoms, like coughing or unexplained weight loss, rather than classic heartburn. Women, particularly during pregnancy, often experience regurgitation due to hormonal changes and increased abdominal pressure. Postmenopausal women may also be at greater risk if estrogen levels influence sphincter tone. Understanding these demographic variations helps contextualize why food might come up when you burp under specific hormonal or age-related circumstances and guides more tailored care.

Can probiotics help with burping up food and regurgitation symptoms?

Probiotics have gained attention for their potential role in regulating gut flora and enhancing digestive function, but their role in regurgitation is more nuanced. Certain probiotic strains, such as Lactobacillus reuteri or Bifidobacterium infantis, have shown promise in reducing bloating and improving motility, which may indirectly help individuals who report that food comes up when they burp. However, results are strain-specific and highly individual. Probiotics may be particularly helpful in cases where symptoms are linked to imbalanced gut bacteria or antibiotic use. It’s advisable to consult a healthcare provider to select the most appropriate formulation and to monitor any changes in symptoms, as some probiotic blends can initially increase gas production before benefits are realized.

Can chronic regurgitation lead to complications if left untreated?

Yes, untreated chronic regurgitation can lead to a number of complications that extend beyond discomfort. Repeated exposure of the esophagus to stomach contents—acidic or otherwise—can result in inflammation, ulceration, and tissue scarring, potentially causing strictures or narrowing. Over time, this may lead to dysphagia or persistent choking episodes. Additionally, regurgitation that reaches the throat or airways can increase the risk of aspiration, especially in older adults or those with swallowing difficulties. If you frequently find that when you burp food comes up into your throat or mouth, it’s more than just an annoyance—it may be setting the stage for long-term esophageal damage or respiratory complications. Seeking timely medical intervention can prevent these outcomes and improve overall digestive resilience.

Final Thoughts: Why Understanding What Causes Regurgitation Matters for Digestive Health

Recognizing what causes regurgitation is more than an academic exercise—it is a necessary step toward reclaiming comfort, confidence, and control over one’s digestive health. Whether symptoms stem from structural dysfunctions like a weak LES or hiatal hernia, behavioral patterns such as rumination or air swallowing, or more systemic conditions like diabetes or scleroderma, early identification and intervention are essential. Equally important is differentiating between benign, occasional regurgitation and signs that may indicate a more serious underlying issue.

For individuals who find themselves saying “when I burp, food comes up” or frequently experience burping up food without warning, these aren’t just isolated inconveniences. They are messages from the body, signaling that something in the digestive system is out of balance. With a holistic and informed approach—encompassing diet, lifestyle, behavior, and medical care—most cases of regurgitation can be effectively managed or even resolved.

By embracing a proactive mindset and working collaboratively with healthcare providers, individuals can achieve not only relief from symptoms but also a deeper understanding of their digestive wellness. In doing so, we move beyond mere symptom control toward comprehensive, long-term digestive health.