For many people, being a “picky eater” is often shrugged off as a personality quirk or a phase that children outgrow. But what happens when selective eating isn’t just a preference but a deeply rooted, disruptive pattern that interferes with physical health, emotional well-being, and social function? What kind of a condition is picky eater behavior when it becomes persistent and extreme? Increasingly, clinicians and researchers are recognizing that what many refer to colloquially as “picky eater disorder” may in fact reflect a diagnosable and serious condition known as ARFID—Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. As our understanding of eating disorders continues to evolve, so too must our awareness of conditions like ARFID, which do not always fit the traditional mold of anorexia or bulimia but are no less impactful.

Avoidant or restrictive eating may sound benign at first, but for those living with ARFID, food-related anxiety and rigid food avoidance can be life-altering. This condition often begins in childhood but can persist into or even begin during adulthood. It is often misunderstood or mischaracterized as fussiness, stubbornness, or even willful behavior, particularly in children. Yet for individuals with ARFID, the struggle with food goes far beyond preferences. It is often deeply entrenched in sensory sensitivity, fear of choking or vomiting, or an overwhelming anxiety associated with unfamiliar foods. Recognizing the medical legitimacy of this condition is the first step in helping individuals find compassionate, evidence-based care.

You may also like: Macronutrients vs Micronutrients: What the Simple Definition of Macronutrients Reveals About Your Diet and Health

Understanding the Nature of ARFID Eating and How It Differs from Other Disorders

ARFID, or Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder, was formally introduced as a diagnosis in the DSM-5 in 2013, signaling a shift in how professionals classify and approach certain types of eating behaviors. Previously, individuals who avoided a wide range of foods but were not preoccupied with body image were often placed under vague, non-specific diagnoses. ARFID filled this gap by providing a framework to identify those whose restrictive eating patterns were not driven by a desire for thinness but by other psychological, sensory, or traumatic factors.

Unlike anorexia nervosa, individuals with ARFID typically do not have distorted body image or fear of weight gain. Instead, their avoidance stems from fear of negative consequences related to eating, such as choking or nausea, or from heightened sensory sensitivities to food textures, colors, or smells. For example, someone might restrict their diet to only a few white-colored foods or avoid anything with a slimy texture. These restrictive behaviors can result in nutritional deficiencies, significant weight loss, or failure to thrive in children.

Importantly, what distinguishes ARFID from ordinary picky eating is the level of interference in daily life. While many children go through phases of selective eating, most eventually expand their palates. In contrast, arfid eating patterns persist and often intensify, affecting physical health, emotional functioning, and social interaction. For example, family meals, school lunches, and social gatherings can become fraught with anxiety and isolation. The seriousness of avoidant eating disorder lies not in the food choices themselves but in the rigid, distressing nature of those choices and their broader consequences.

Identifying the Signs: When Picky Eating Crosses the Line into a Disorder

Determining what kind of a condition is picky eater behavior requires careful evaluation of symptoms and their impact. In ARFID, food restriction is typically extreme, consistent, and functionally impairing. The DSM-5 outlines several diagnostic criteria, including significant weight loss (or failure to gain weight appropriately in children), nutritional deficiencies, dependence on nutritional supplements, and marked interference with social or occupational functioning.

Parents, caregivers, and healthcare providers often face the challenge of distinguishing ARFID from developmentally appropriate picky eating. Children are notorious for strong food preferences, and many will avoid vegetables or resist new foods. However, when these habits persist beyond early childhood and lead to noticeable health or psychological issues, a deeper concern may be present. For instance, if a child eats only five types of food and refuses all others regardless of hunger or context, or if mealtimes provoke intense distress or conflict, it may signal arfid food disorder rather than ordinary selectiveness.

Adults, too, can be affected by ARFID, although the condition is more commonly identified in children. In adults, restrictive eating disorder behaviors may manifest as long-standing eating habits that have never expanded or evolved. These patterns may be socially tolerated or explained away, leading to delayed diagnosis and untreated symptoms. Common signs include extreme fear of new foods, frequent gastrointestinal complaints unrelated to medical issues, and a tendency to avoid social situations involving food. Recognizing these red flags early can enable timely intervention and better outcomes.

Psychological Underpinnings and Contributing Factors in ARFID

Understanding the psychology behind arfid eating requires a look at several overlapping factors. Sensory processing differences are often central, particularly in children with neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). For these individuals, certain textures or smells may be overwhelming, even painful. Their aversion is not a matter of will but of heightened sensitivity. Likewise, a history of gastrointestinal illness, choking incidents, or other traumatic experiences involving food can lead to food-related anxiety that reinforces restrictive patterns.

Anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive traits frequently co-occur with ARFID. This is one reason why eating disorder arfid can be especially persistent and complex to treat. For instance, a child who once vomited after trying a new food might associate all new foods with that negative experience, leading to a learned avoidance behavior reinforced over time. Similarly, someone with contamination fears might avoid certain categories of food altogether, fearing illness or exposure to germs. These psychological underpinnings mean that treatment often requires more than just nutritional guidance—it must also include behavioral and cognitive strategies to address underlying anxiety.

Moreover, cultural and familial attitudes toward food can play a role. In some households, rigid eating expectations or pressure to eat everything on the plate may exacerbate food aversion. Well-intentioned efforts to correct picky eating may backfire if they increase the child’s distress or reinforce negative associations with mealtime. When evaluating avoidant eating disorder, clinicians must consider the broader context of the individual’s environment, experiences, and emotional health. A holistic view is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective care.

Medical and Nutritional Consequences of ARFID

The physical consequences of arfid food disorder can be serious and wide-ranging. Due to the limited variety of accepted foods, individuals with ARFID are at high risk of nutritional deficiencies, which may affect growth, immune function, and energy levels. Common deficiencies include iron, zinc, vitamin A, vitamin C, and various B vitamins. In children, inadequate calorie intake can impair height and weight progression, potentially leading to failure to thrive. In adults, chronic undernutrition may contribute to fatigue, poor wound healing, and hormonal imbalances.

In some cases, individuals may rely heavily on nutritional shakes or supplements to compensate for their limited diet. While these can provide short-term relief, they do not address the root of the restrictive eating disorder and may contribute to further food avoidance. Additionally, dependence on liquid nutrition can affect gastrointestinal function and oral motor skills, especially in young children who miss out on chewing and swallowing experiences vital to feeding development.

Digestive issues are also common in ARFID. Complaints of nausea, bloating, or abdominal pain may occur even in the absence of identifiable medical conditions. These symptoms can perpetuate food aversion by reinforcing the belief that eating causes discomfort. In such cases, a multidisciplinary evaluation that includes medical, nutritional, and psychological assessments is critical. Proper diagnosis allows for individualized treatment strategies that prioritize both physical and emotional recovery.

Diagnosis and Treatment: A Multidisciplinary Approach to ARFID

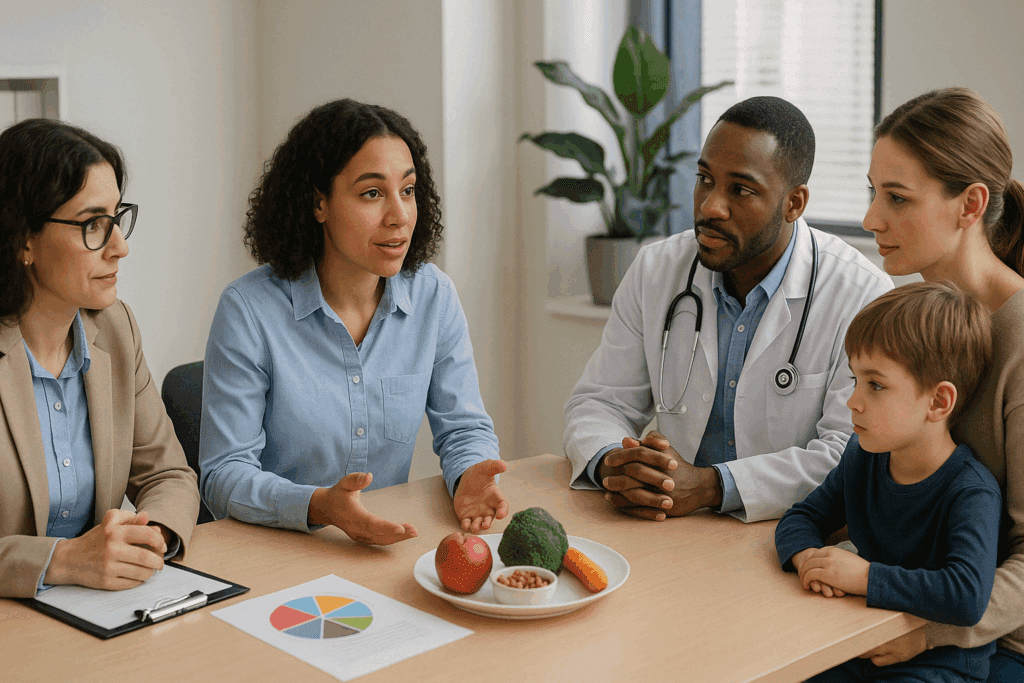

Diagnosing eating disorder arfid requires careful assessment by clinicians trained in both mental health and nutrition. The process typically begins with a comprehensive evaluation of dietary habits, growth patterns, medical history, and psychosocial factors. Standardized screening tools, such as the Eating Disorder Examination for ARFID (EDE-ARFID), may be used to support the diagnosis. Laboratory tests may also be conducted to identify nutritional deficiencies and rule out other medical conditions.

Once diagnosed, treatment for ARFID is most effective when it involves a team approach. Ideally, this team includes a psychologist or therapist with experience in eating disorders, a registered dietitian, and a medical provider. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for ARFID (CBT-AR) is currently one of the most evidence-based treatments and focuses on gradually increasing food variety while addressing anxiety and avoidance behaviors. This structured but flexible approach helps individuals challenge distorted beliefs about food and develop coping skills for managing distress.

In some cases, exposure therapy may be used to desensitize individuals to feared foods or textures. Occupational therapists with expertise in sensory integration can also play a vital role, especially for children with co-occurring sensory processing issues. For more severe cases, inpatient or intensive outpatient programs may be necessary to stabilize nutrition and support behavior change. Recovery is often gradual, requiring patience, empathy, and ongoing support from both professionals and family members.

Social Impacts and Emotional Toll of Living with ARFID

Living with avoidant eating disorder can be profoundly isolating. Meals, which are often social and communal events, may instead become sources of anxiety, embarrassment, or avoidance. Children with ARFID may be teased or excluded by peers during lunchtime at school, while adults may struggle to participate in work events, holidays, or dinners with friends. These experiences can lead to social withdrawal, low self-esteem, and increased risk for depression or anxiety.

The emotional burden also extends to families. Parents often report feeling helpless, frustrated, or blamed for their child’s restrictive eating. Mealtimes may become battlegrounds, eroding family harmony and increasing stress. It is not uncommon for caregivers to cycle through a range of strategies—coaxing, bribing, demanding—only to find that none produce lasting change. Professional support can help families move away from these cycles and toward more constructive, supportive interactions.

Self-image can also be impacted in subtle but significant ways. While ARFID is not driven by body image concerns, the experience of being “different” or “difficult” can affect a person’s sense of identity. Some individuals internalize shame or guilt about their eating habits, particularly if they have received negative comments or been misunderstood. Recognizing and validating these emotional experiences is a crucial part of treatment and recovery.

Raising Awareness and Reducing Stigma Around Picky Eater Disorder

One of the greatest barriers to treatment for arfid food disorder is the stigma and misunderstanding that surrounds it. Because picky eating is so common in early childhood, many people, including healthcare providers, may minimize the severity of ARFID symptoms or attribute them to poor parenting. This delay in recognition can result in years of unnecessary suffering and preventable health complications. Public education campaigns and professional training are essential to improving awareness and access to care.

Media portrayals and cultural narratives also play a role in shaping how we view eating behavior. The archetype of the picky eater is often played for laughs or dismissed as quirky. But when this stereotype obscures the reality of restrictive eating disorder, it does a disservice to those affected. ARFID deserves the same level of seriousness and support as any other eating disorder. When we ask, “what kind of a condition is picky eater behavior,” we must answer with clinical accuracy, compassion, and respect.

School systems, pediatricians, and mental health professionals can all be agents of change by recognizing early warning signs and referring families to appropriate specialists. Likewise, employers and universities can create inclusive environments that accommodate diverse dietary needs without stigma. Small changes in language and attitude can have a significant impact on how individuals with ARFID are perceived and treated.

Looking Ahead: Research, Innovation, and Hope for the Future

Research into arfid eating is still relatively new but growing rapidly. Emerging studies are exploring the neurobiological basis of food aversion, the role of anxiety circuitry, and the effectiveness of various treatment modalities. There is also increasing interest in developing tools for earlier detection and more accurate assessment. As awareness spreads, more individuals are coming forward to share their stories, helping to destigmatize the condition and advocate for better resources.

Technological innovations such as telehealth are expanding access to care, especially in underserved areas. Virtual platforms can connect families with specialized therapists and dietitians who understand eating disorder arfid and can provide tailored interventions. Digital apps that support exposure therapy or track nutritional progress are also being explored as supplementary tools for treatment.

Perhaps most importantly, the conversation around food, health, and mental well-being is evolving. More people are recognizing that eating disorders come in many forms, and that all deserve attention and care. By building a more inclusive understanding of picky eater disorder and its many manifestations, we can create a health system that better serves those who have long felt unseen.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Understanding ARFID and Picky Eater Disorder

1. How is ARFID different from traditional food phobias or allergies? While food allergies are immune-based responses to specific food proteins and phobias may relate to psychological trauma, ARFID eating behaviors typically combine sensory sensitivity, anxiety, and cognitive rigidity. People with avoidant eating disorder often avoid foods not because they fear an allergic reaction but due to intense discomfort with the food’s texture, smell, or appearance. In contrast to phobias that usually stem from a specific traumatic event, ARFID-related fear can develop gradually through repeated negative experiences or heightened sensory awareness. Understanding what kind of a condition is picky eater behavior in this context requires acknowledging how deeply rooted these aversions are in the person’s cognitive and emotional processing. ARFID is thus more complex and functionally impairing than a typical food phobia or medically diagnosed allergy.

2. Can ARFID develop in adulthood, or is it only a childhood disorder? Contrary to common belief, ARFID is not confined to childhood. While many cases begin early in life, adult-onset ARFID is a growing area of clinical interest. For some individuals, what begins as mild picky eater disorder in childhood can persist or worsen with age due to increased social isolation or anxiety. Others may develop avoidant eating disorder later in life following a traumatic experience with food, such as choking or severe gastrointestinal illness. This highlights the importance of assessing arfid food disorder across all age groups, especially since adults may mask their symptoms behind socially acceptable justifications like “being a foodie with preferences.”

3. What are the long-term effects of untreated restrictive eating disorder? Left untreated, restrictive eating disorder behaviors can lead to serious medical and psychological complications. Malnutrition, stunted growth, and bone density loss are physical risks, particularly for children and adolescents. Over time, arfid eating can also damage self-esteem and hinder relationship development, especially when social events revolve around food. Individuals may miss out on cultural, familial, and professional opportunities due to dietary limitations and associated anxiety. Recognizing what kind of a condition is picky eater behavior when it causes such widespread dysfunction is key to providing early and effective intervention.

4. How can families support a loved one struggling with ARFID without causing additional stress? Supporting someone with eating disorder arfid requires empathy, patience, and informed strategies. Avoid labeling behaviors as stubborn or manipulative, as this reinforces shame. Instead, encourage small exposures to new foods in low-pressure environments and consider involving an occupational therapist or psychologist experienced in avoidant eating disorder. It also helps to involve the person in meal planning so they feel a sense of control. Recognizing the seriousness of arfid food disorder can change how families approach meals—not as battlegrounds, but as opportunities for gradual progress.

5. Are there any emerging treatments for ARFID beyond traditional therapy? Recent innovations in the treatment of arfid eating include virtual reality exposure therapy, which allows individuals to practice tolerating food-related stimuli in a controlled environment. Additionally, there is growing interest in using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to help individuals tolerate discomfort while aligning their behaviors with personal values. Biofeedback and neurofeedback techniques may also help those with heightened sensory or anxiety responses. While Cognitive Behavioral Therapy remains the gold standard, these complementary approaches may expand treatment accessibility and effectiveness. Understanding avoidant eating disorder as a neurocognitive and emotional challenge opens the door to creative, science-backed interventions.

6. What role do schools play in identifying and managing picky eater disorder in children? Schools can be vital in spotting early signs of arfid food disorder, particularly during lunchtime or snack breaks. Teachers and school nurses who observe consistent food avoidance or emotional distress around eating should document these patterns and communicate with parents. School counselors can also facilitate referrals to specialists when needed. Creating an inclusive dining environment—such as allowing flexible seating or food substitution without stigma—can reduce stress for students with avoidant eating disorder. By recognizing what kind of a condition is picky eater behavior at school, educators become essential partners in early detection and support.

7. Is there a genetic or biological component to ARFID? Emerging research suggests that there may be a genetic predisposition to ARFID, especially among individuals with family histories of anxiety, sensory processing disorders, or autism spectrum traits. Studies are exploring how certain neurobiological pathways related to sensory integration and interoception influence arfid eating tendencies. Although no single gene has been identified, the presence of co-occurring neurodevelopmental conditions points to a possible heritable risk. Understanding eating disorder arfid as part of a broader neurodevelopmental landscape, rather than as purely behavioral, helps frame treatment with more nuance and compassion. Genetics alone don’t cause ARFID, but they may help explain why some individuals are more susceptible to picky eater disorder than others.

8. Can nutritional supplements replace a varied diet in individuals with ARFID? While supplements can help bridge short-term nutritional gaps, they are not a long-term substitute for a diverse, whole-food diet. People with arfid food disorder often rely on liquid nutrition or meal replacements, which may support basic health but fail to engage essential sensory and oral-motor skills. Over-reliance on supplements can also limit progress by reinforcing food avoidance behaviors. Registered dietitians specializing in restrictive eating disorder can help individuals slowly expand their food repertoires without overwhelming them. Ultimately, restoring function through real food is a vital part of overcoming avoidant eating disorder.

9. How do cultural beliefs and values affect the experience of ARFID? Cultural norms around food and mealtimes can either exacerbate or alleviate arfid eating challenges. In cultures where communal eating is central, individuals with eating disorder arfid may experience heightened shame or alienation. Conversely, cultures that embrace food individuality and dietary flexibility may reduce the psychological burden. Cultural expectations also shape how picky eater disorder is perceived—as a minor inconvenience or a serious health issue. A culturally competent approach to arfid food disorder recognizes the importance of social context while tailoring interventions to respect both individual needs and cultural values.

10. What steps can healthcare providers take to improve ARFID diagnosis and treatment? Healthcare professionals can enhance ARFID recognition by integrating routine screening questions about food avoidance and sensory sensitivities during physical exams. Pediatricians, in particular, should track growth trajectories alongside dietary variety to identify early red flags of avoidant eating disorder. Continuing education for dietitians, therapists, and primary care providers is essential to ensuring accurate diagnosis and referral. By understanding what kind of a condition is picky eater behavior in clinical terms, providers can avoid mislabeling symptoms as developmental delays or behavioral problems. Collaboration across specialties—including psychology, nutrition, and gastroenterology—yields the most effective outcomes for those navigating restrictive eating disorder.

Final Thoughts: Why Understanding Avoidant or Restrictive Eating Matters

In answering the question, “what kind of a condition is picky eater behavior,” we uncover a complex and deeply personal reality that affects thousands of children and adults. ARFID is not a phase or a personality flaw; it is a legitimate eating disorder that requires understanding, empathy, and evidence-based care. The medical community, families, and society at large must recognize that restrictive eating disorder is not always about weight or body image, but can be just as serious and deserving of intervention.

From nutritional deficiencies to social isolation and emotional distress, arfid food disorder casts a wide net of impact. However, with proper diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment, recovery is not only possible but probable. As we continue to learn more about the roots and manifestations of avoidant eating disorder, we must also ensure that stigma, misinformation, and cultural assumptions do not stand in the way of healing.

Greater awareness, earlier intervention, and ongoing research will all play critical roles in improving outcomes for those with eating disorder arfid. And by shifting the conversation from blame to understanding, from minimization to medical legitimacy, we open the door to a more compassionate and informed future for all those who struggle with food-related anxiety and restriction.

Further Reading:

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

Understanding ARFID: More Than Just Picky Eating

ARFID eating disorder: Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder