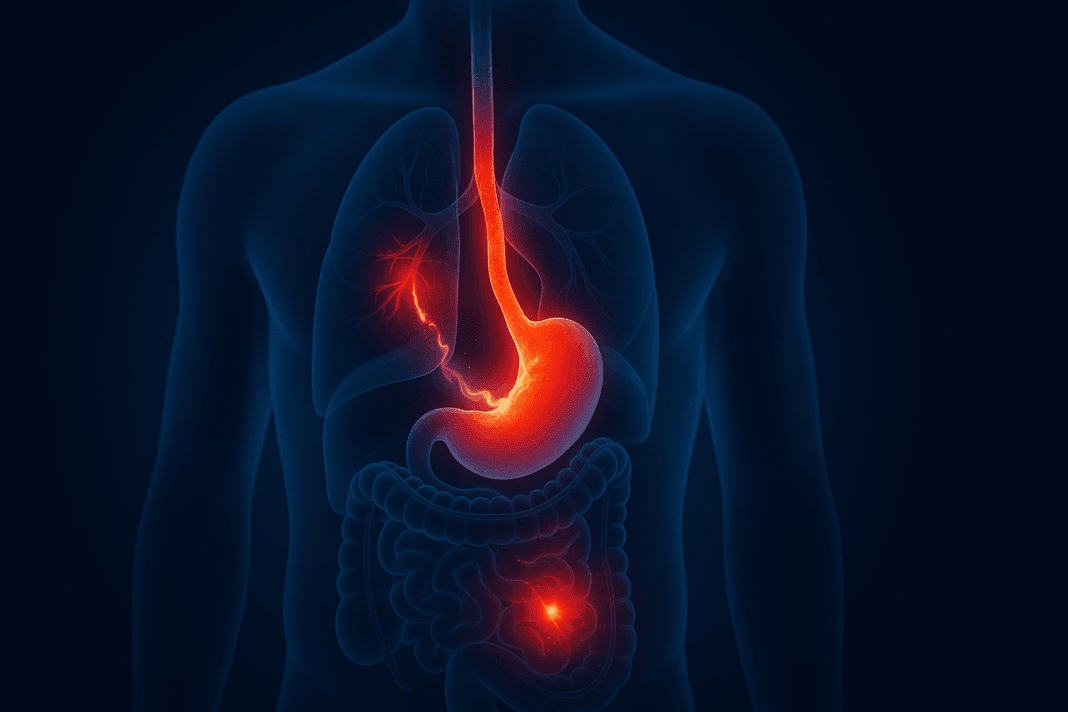

Understanding how digestive disorders present themselves is key to accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. Among the many questions that patients and clinicians explore is: can GERD cause lower abdominal pain? While GERD—short for gastroesophageal reflux disease—is primarily known for symptoms like heartburn, chest discomfort, and regurgitation, emerging evidence and clinical observations suggest a broader symptom spectrum that may extend to the lower abdomen. For those suffering from unexplained abdominal pain that does not respond to typical gastrointestinal treatments, GERD may be an underrecognized contributor. Unraveling this possibility requires exploring how reflux disease interacts with the wider digestive system and how its symptoms may go beyond the esophagus.

GERD is often considered a condition limited to the upper gastrointestinal tract, largely because its defining symptoms originate in the esophagus and stomach. However, the body’s digestive system is highly interconnected, and disturbances in one part can have cascading effects in others. The possibility that acid reflux may be associated with lower abdominal pain invites a closer look at the physiological, neurological, and functional relationships within the digestive network. As we examine these interrelationships, we uncover a more nuanced understanding of how symptoms like lower abdominal discomfort can, in some cases, be traced back to conditions like GERD.

You may also like: How Long Does GERD Last in Adults? Expert Insights on This Common Yet Persistent Digestive Condition

GERD and the Broader Scope of Digestive Health

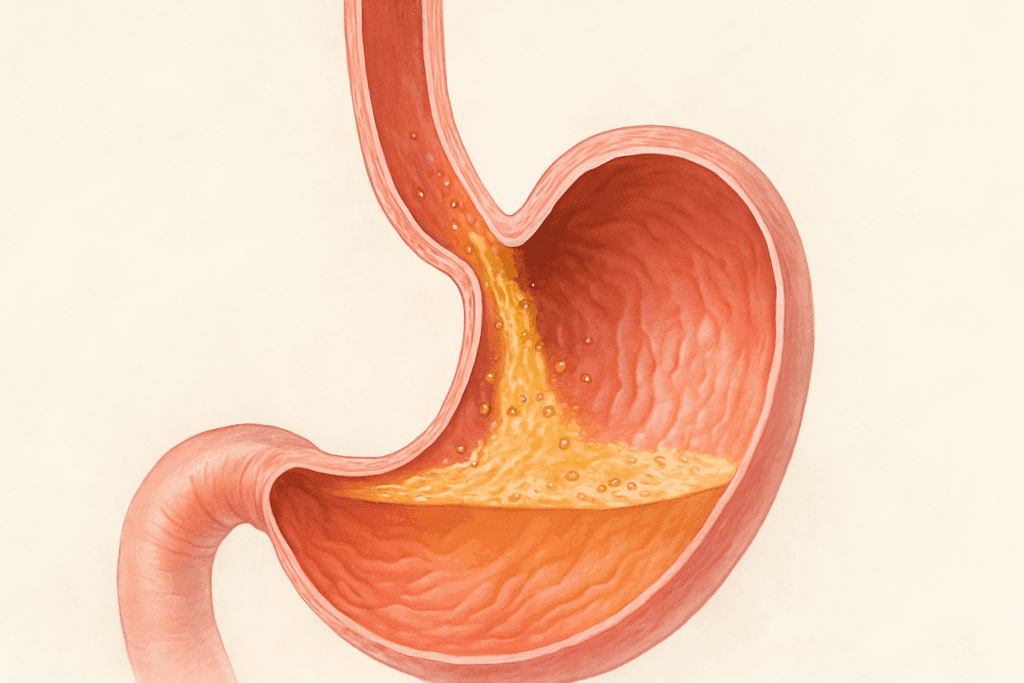

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a chronic and often progressive disorder that occurs when stomach acid persistently backs up into the esophagus. This reflux typically results from a malfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the muscular valve that separates the esophagus from the stomach. When the LES fails to close properly, acid and digestive enzymes can escape upward, irritating the delicate lining of the esophagus and causing symptoms such as heartburn, sour taste, chest pain, and even difficulty swallowing.

What makes GERD particularly challenging is its variability in presentation. While some individuals experience classic reflux symptoms, others may have what is known as silent reflux, where damage occurs without the typical burning sensation. Moreover, GERD can manifest with extraesophageal symptoms such as chronic cough, sore throat, hoarseness, and even asthma-like wheezing. This variability underscores how GERD’s reach may extend further than commonly assumed.

In clinical practice, patients with GERD frequently report sensations of pressure or bloating that may not be confined to the upper abdomen. A recurring complaint among some individuals is a feeling of general abdominal discomfort that lacks a clear anatomical source. For these patients, understanding the potential for GERD to be implicated in lower abdominal symptoms may lead to more effective management and relief.

Understanding Abdominal Pain: Upper vs. Lower Origins

Abdominal pain is a common yet complex symptom that can arise from multiple organ systems and anatomical regions. To better evaluate the potential relationship between GERD and pain localized in the lower abdomen, it is important to distinguish between upper and lower abdominal anatomy and symptom patterns.

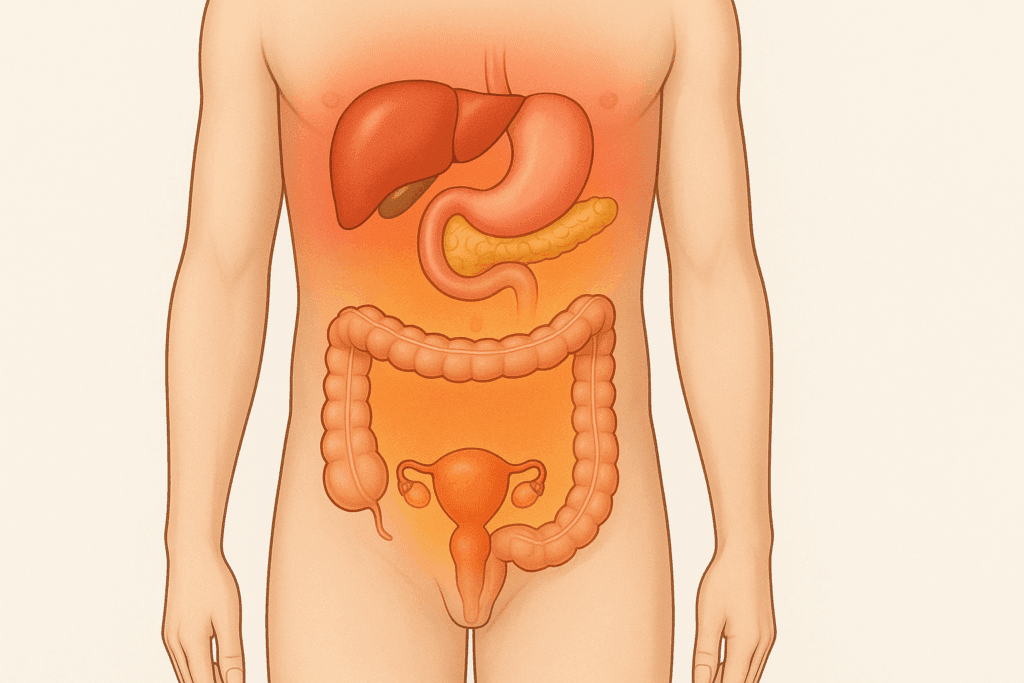

The upper abdomen encompasses organs such as the stomach, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder. Pain in this area, particularly upper stomach pain burning in nature, is more readily associated with acid reflux and related conditions like gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. When patients report burning sensations, particularly after meals or when lying down, GERD is often a primary suspect.

By contrast, the lower abdomen contains portions of the small and large intestines, reproductive organs, and parts of the urinary tract. Pain in this region is often attributed to conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), diverticulitis, ovarian cysts, or bladder infections. The idea that GERD might contribute to discomfort in this region is less intuitive but not without precedent. Several physiological processes may help explain how symptoms traditionally linked to upper gastrointestinal function can radiate downward or contribute to diffuse discomfort.

Pain referral patterns are one such explanation. The nervous system sometimes misinterprets signals from internal organs, resulting in pain that is perceived in a different location from its origin. Additionally, disrupted motility and inflammation caused by GERD may affect neighboring or downstream digestive structures, potentially resulting in lower abdominal sensations.

Can GERD Cause Lower Abdominal Pain? Exploring the Underlying Mechanisms

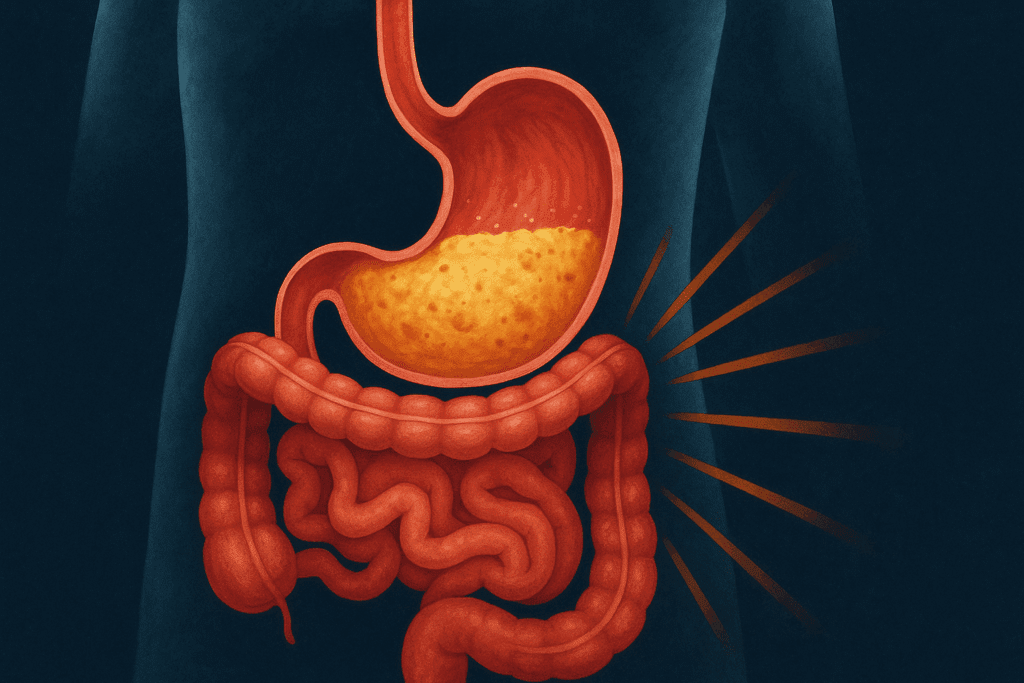

When clinicians and researchers investigate whether GERD can cause lower abdominal pain, they are delving into a multifactorial web of digestive interactions. While GERD does not directly affect the lower abdomen in the same way it impacts the esophagus or stomach, it can create conditions that contribute to discomfort lower in the gastrointestinal tract.

One of the most relevant mechanisms is delayed gastric emptying, a condition often found in people with GERD. This phenomenon, also known as gastroparesis, results in the stomach taking longer than usual to empty its contents into the small intestine. When this occurs, food and acid accumulate, leading to pressure, bloating, and a sense of fullness that may radiate downward into the lower abdomen. Although not caused exclusively by GERD, gastroparesis frequently coexists with it and can exacerbate abdominal symptoms.

Another important consideration is the presence of visceral hypersensitivity. In this state, the nerves that supply the gastrointestinal tract become unusually sensitive, leading to amplified perceptions of pain. Individuals with GERD often exhibit increased visceral sensitivity not only in the esophagus but also in broader regions of the digestive tract. This sensitivity may heighten the experience of abdominal discomfort, even in areas not directly exposed to refluxed acid.

Moreover, the systemic inflammatory effects of GERD may play a role. Chronic reflux can result in local and systemic inflammation that alters gut function, motility, and microbial balance. Inflammation-related disruptions may contribute to symptoms classically linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders, including cramping, urgency, and changes in bowel habits—all of which may manifest as or contribute to lower abdominal pain.

The GERD-IBS Connection: Overlapping Symptoms and Shared Pathways

One of the most frequently observed patterns in patients with GERD is its co-occurrence with irritable bowel syndrome. IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel movements in the absence of overt pathology. The overlap between GERD and IBS is significant, with studies suggesting that nearly 40% of individuals with one condition also meet the criteria for the other.

This coexistence is not coincidental. Both GERD and IBS are thought to involve alterations in gut-brain signaling, visceral hypersensitivity, and dysregulated motility. Patients with both conditions often report symptoms that wax and wane in response to stress, dietary triggers, and hormonal changes. Additionally, the gut microbiota—an increasingly recognized player in gastrointestinal health—appears to be altered in both GERD and IBS, suggesting a shared underlying disruption in microbial ecology.

When GERD and IBS occur together, distinguishing the primary driver of symptoms becomes difficult. For example, a patient may present with upper stomach pain GERD typically causes, alongside lower abdominal cramping and bowel irregularities. In such cases, treatment may need to target both acid suppression and strategies for managing IBS symptoms such as fiber modulation, antispasmodics, and stress reduction techniques.

The diagnostic overlap between GERD and IBS highlights the need for comprehensive symptom assessment. Rather than viewing digestive conditions in isolation, clinicians are increasingly encouraged to take a systems-based approach that recognizes the interconnected nature of gastrointestinal disorders. This shift in perspective can lead to more personalized treatment plans and improved patient outcomes.

Why Pain Perception Can Be Misleading in GERD

Another aspect to consider when evaluating symptoms like lower abdominal discomfort is the nature of pain perception itself. Pain in the gastrointestinal tract is not always localized to the precise site of pathology. Instead, it may be referred or radiated due to the complexity of visceral innervation. This phenomenon is especially relevant in conditions like GERD, where irritation and inflammation in one area—such as the esophagus or stomach—can activate neural pathways that lead to perceived pain elsewhere in the abdomen.

The vagus nerve, which extends from the brainstem to various digestive organs, plays a central role in transmitting sensory information from the gut to the brain. When this nerve is stimulated by acid reflux, it can produce symptoms that feel like they originate far from the source. For example, GERD-related stimulation of the vagus nerve can trigger sensations in the chest, throat, and even the lower abdomen, creating diagnostic confusion.

Furthermore, chronic activation of pain pathways can result in central sensitization, a state where the nervous system becomes hyper-responsive to stimuli. In people with chronic GERD, this sensitization can blur the lines between where symptoms originate and where they are felt. As a result, a reflux episode may produce a complex constellation of sensations, including those interpreted as lower abdominal pain—even when no pathology exists in that region.

This mismatch between symptom origin and symptom location complicates both self-reporting and clinical evaluation. Patients may be tempted to focus on the area where they feel discomfort, rather than considering how interconnected their symptoms may be. Healthcare providers, in turn, must keep an open mind about the broader implications of seemingly localized complaints, particularly when dealing with chronic or overlapping gastrointestinal disorders.

Evaluating Related Symptoms: When Acid Reflux Feels Like More Than Heartburn

Acid reflux symptoms can present in a variety of ways, and one of the more surprising manifestations is pain on the right side of the body. Although commonly overlooked, acid reflux right side pain can occur, especially in individuals who sleep or recline on their right side. Anatomically, lying on the right side can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and promote acid movement into the esophagus, increasing discomfort. This positioning may also lead to a sense of fullness or pressure that migrates downward, possibly contributing to pain that is mistaken for lower abdominal or even flank issues.

Beyond sleep positioning, the progression of reflux disease can result in persistent symptoms that transcend the upper gastrointestinal tract. For instance, GERD may cause chronic throat clearing, laryngitis, sinus problems, and even a sensation of a lump in the throat—symptoms not immediately linked to acid reflux. Similarly, people may experience generalized abdominal discomfort or bloating, which are typically associated with conditions like IBS but can be secondary to poor gastric function caused by reflux disease.

Upper stomach pain GERD can provoke often starts as a burning sensation behind the breastbone but can radiate upward or downward, mimicking other digestive or even cardiac issues. Because of this variability, many GERD patients undergo extensive diagnostic workups before a clear link between their symptoms and reflux is established. Endoscopy, pH monitoring, and motility studies may be necessary to confirm GERD and rule out alternative explanations for symptoms such as lower abdominal pain.

Understanding that GERD can manifest in atypical ways—including pain that feels like it originates in the lower abdomen—empowers both patients and providers to pursue broader diagnostic considerations. With better awareness, individuals may recognize GERD not only as a condition of the esophagus but as a possible contributor to diverse and widespread discomfort throughout the abdominal cavity.

Lifestyle Factors and Digestive Patterns That Link GERD to Lower Abdominal Symptoms

The role of lifestyle in both the development and progression of GERD is well established. Diet, physical activity, stress levels, and sleep hygiene all influence the severity and frequency of acid reflux. These same lifestyle elements can also affect bowel function, making them potential mediators of symptoms throughout the digestive tract, including the lower abdomen.

Diet is perhaps the most significant lifestyle factor in managing GERD. Foods that are spicy, fatty, acidic, or caffeinated can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and increase acid production, worsening reflux symptoms. However, these same foods may also irritate the intestines or disrupt gut flora, leading to gas, bloating, and lower abdominal cramping. When people experience GERD alongside these symptoms, it’s possible that dietary habits are contributing to both upper and lower gastrointestinal discomfort.

Meal timing and portion sizes also play a role. Eating large meals or eating too close to bedtime increases the risk of reflux by overloading the stomach and increasing intra-abdominal pressure. This can slow digestion and promote fermentation, which may result in bloating, altered bowel movements, and pain in the lower abdomen. The overlap in symptoms often leads to diagnostic confusion, particularly when GERD and IBS coexist.

Another significant contributor is stress. Chronic stress has been shown to influence digestive motility, gut sensitivity, and acid secretion. For individuals with GERD, stress may exacerbate reflux symptoms and simultaneously provoke intestinal symptoms typical of IBS. In this way, stress becomes a unifying factor that worsens symptoms across the entire digestive tract, including those experienced as lower abdominal pain.

Encouraging patients to track their lifestyle habits in relation to symptom onset can be a powerful diagnostic and therapeutic tool. Keeping a food and symptom diary may help identify triggers that contribute to both reflux and abdominal discomfort. Combining this approach with targeted medical therapy can help break the cycle of recurring symptoms and improve overall quality of life.

Medical Conditions That Mimic GERD and Lower Abdominal Pain

Given the potential for GERD to overlap with other digestive disorders, it is important to consider medical conditions that may mimic its symptoms. Not all cases of abdominal discomfort—whether upper or lower—can be attributed to reflux, and a thorough differential diagnosis is essential.

Peptic ulcer disease, gallstones, and pancreatitis are examples of upper gastrointestinal conditions that can cause burning or gnawing pain similar to GERD. Meanwhile, diverticulitis, appendicitis, endometriosis, and urinary tract infections may present as lower abdominal pain, and distinguishing them from GERD-related manifestations is critical. A combination of patient history, physical examination, imaging studies, and endoscopy may be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is also worth noting that medications used to treat GERD—such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 blockers—can sometimes contribute to symptoms in other parts of the digestive tract. Long-term acid suppression may alter gut flora or lead to malabsorption of nutrients like magnesium and vitamin B12, which can result in symptoms such as fatigue, bloating, and abdominal discomfort. These side effects can complicate the clinical picture, making it difficult to determine whether symptoms are caused by the disease, the treatment, or both.

Functional disorders also deserve consideration. In addition to IBS, conditions such as functional dyspepsia and non-cardiac chest pain often overlap with GERD and may produce pain in various parts of the abdomen. These disorders are characterized by symptoms that are real and distressing, yet lack clear structural or biochemical causes. For patients with overlapping symptoms, a multidisciplinary approach that includes gastroenterology, psychology, and nutrition may be beneficial.

How GERD Management May Alleviate Lower Abdominal Pain

If GERD is indeed contributing to lower abdominal discomfort, then effective management of reflux may offer relief beyond the esophagus. The cornerstone of GERD treatment involves a combination of lifestyle changes and pharmacological therapy, both of which may have downstream effects on lower abdominal symptoms.

Pharmacological therapy typically begins with acid suppression using proton pump inhibitors or H2 receptor antagonists. These medications reduce gastric acid production, thereby minimizing esophageal irritation and the cascade of symptoms it may trigger. For patients who also experience bloating or bowel irregularities, prokinetic agents that improve gastrointestinal motility may be added to enhance gastric emptying and reduce pressure-related symptoms.

Lifestyle interventions remain a critical aspect of treatment. Patients are encouraged to avoid trigger foods, eat smaller and more frequent meals, avoid eating late at night, and elevate the head of their bed to prevent nocturnal reflux. These strategies can reduce intra-abdominal pressure and improve both upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms.

In patients with coexisting IBS, a low FODMAP diet may be helpful. This dietary approach restricts fermentable carbohydrates that can contribute to gas, bloating, and abdominal pain. While initially developed for IBS, the low FODMAP diet has shown promise in reducing symptoms in patients with functional heartburn and reflux hypersensitivity, suggesting a role for dietary modulation in treating both conditions.

Stress management techniques such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and regular physical activity can also improve symptoms. These interventions not only reduce stress-related exacerbations of GERD but may also regulate bowel function and decrease visceral sensitivity in the lower abdomen.

By treating GERD comprehensively, patients may find that symptoms they previously attributed to unrelated causes—such as lower abdominal pain—begin to subside. This reinforces the importance of holistic, systems-based care that considers how various parts of the digestive tract influence each other.

Recognizing When Lower Abdominal Pain Requires Further Evaluation

While it is now clearer that GERD may play a role in contributing to lower abdominal discomfort, it is equally important to recognize the boundaries of that relationship. Not all abdominal pain should be attributed to GERD, particularly when symptoms are severe, persistent, or accompanied by alarming signs. In some cases, lower abdominal pain may be a warning sign of more serious conditions that require immediate medical evaluation.

Red flag symptoms include unexplained weight loss, rectal bleeding, persistent vomiting, severe tenderness on palpation, and anemia. These signs suggest the possibility of underlying pathology such as malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, or infectious processes that go beyond the scope of reflux disease. In such cases, further diagnostic testing is warranted, including colonoscopy, abdominal imaging, and laboratory evaluation.

Patients who do not respond to standard GERD therapy should also be reevaluated. Refractory symptoms may indicate incorrect diagnosis, poor adherence to treatment, or the presence of a coexisting condition such as eosinophilic esophagitis or functional abdominal pain syndrome. Moreover, individuals who have been on long-term proton pump inhibitors without symptom relief should be assessed for potential side effects, drug resistance, or alternative causes of their discomfort.

A key part of clinical decision-making lies in the patient’s narrative. A detailed symptom history—one that explores timing, quality, location, and aggravating or relieving factors—can offer critical clues. For example, if a patient reports that their lower abdominal pain improves with acid-suppressive therapy or changes in dietary patterns typical for GERD management, this may support the idea of a reflux-related mechanism. On the other hand, worsening symptoms despite optimized GERD treatment may point to a different cause.

Clinicians must remain vigilant and not allow a diagnosis of GERD to create tunnel vision. While GERD is common and frequently implicated in a wide array of symptoms, it is not the sole explanation for abdominal pain, and its presence does not rule out other gastrointestinal or systemic disorders. A thoughtful, evidence-based approach is necessary to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure that patients receive the most effective care possible.

Bridging the Gap: How GERD Research Is Evolving

Our understanding of GERD has expanded significantly over the last two decades, thanks to advances in gastroenterological research. Once thought to be a straightforward disorder caused by excess stomach acid, GERD is now recognized as a complex, multifactorial condition with wide-reaching implications. This evolving view is particularly relevant when assessing connections between GERD and symptoms like lower abdominal pain.

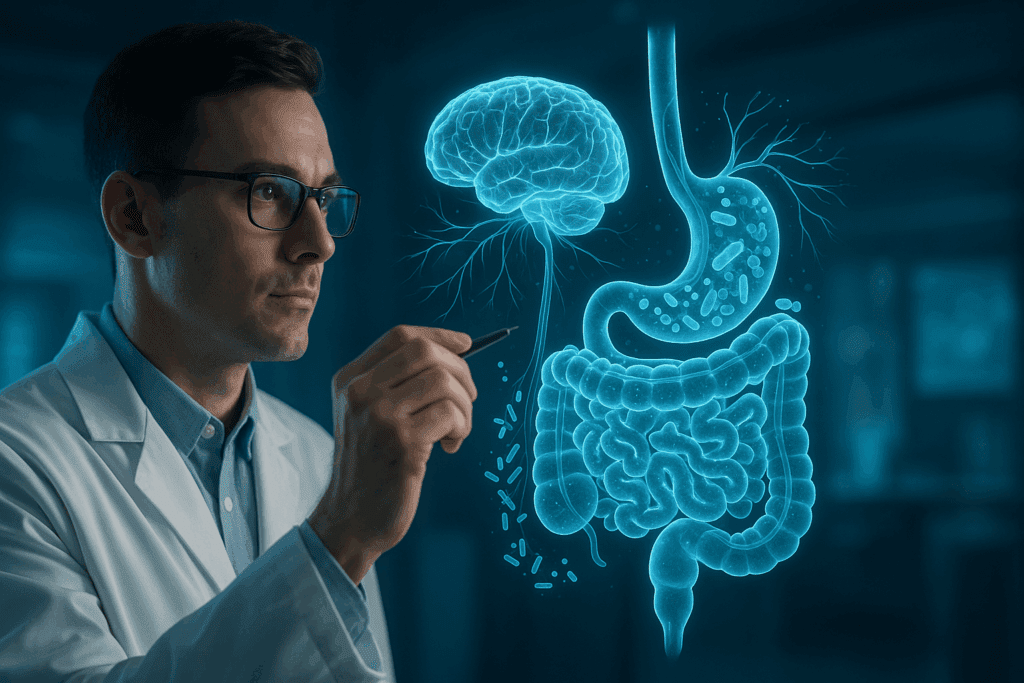

One promising area of research focuses on the gut-brain axis—the bidirectional communication system between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. This axis plays a crucial role in regulating digestive function, pain perception, and emotional responses. In both GERD and functional disorders like IBS, disturbances in the gut-brain axis are thought to contribute to symptom development. Understanding these interactions may help explain why some individuals with GERD report lower abdominal symptoms that extend beyond the primary site of acid reflux.

Another area gaining attention is the role of microbiota in GERD. The microbial communities that reside in the gut influence immunity, motility, inflammation, and sensory signaling. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in gut flora, has been implicated in the development and progression of GERD as well as IBS. Research into how restoring microbial balance—through probiotics, prebiotics, or dietary interventions—can affect symptom control is ongoing, and preliminary findings are encouraging.

There is also increasing interest in non-pharmacological therapies for GERD, such as diaphragmatic breathing, acupuncture, and integrative medicine. These approaches aim to improve esophageal function, reduce reflux episodes, and alleviate pain without relying solely on acid suppression. Some small studies suggest that these techniques may be especially useful in patients with overlapping GERD and IBS symptoms, offering another potential avenue for addressing lower abdominal discomfort in the context of reflux disease.

As our understanding of GERD deepens, so too does our ability to recognize its broader clinical presentations. The notion that GERD can contribute to lower abdominal pain is no longer speculative but part of a growing recognition of how complex and individualized gastrointestinal disorders can be. Future research will continue to refine these insights and inform more targeted, effective treatments.

Practical Steps for Patients: Managing GERD and Lower Abdominal Pain Holistically

For patients experiencing both reflux symptoms and lower abdominal discomfort, a holistic approach to management can be particularly effective. Rather than addressing each symptom in isolation, individuals may benefit from an integrative plan that considers the interplay between different parts of the digestive tract and the broader context of their lifestyle, stress levels, and nutritional habits.

The first step is education. Understanding that GERD and lower abdominal pain may be connected helps patients take a proactive role in their care. By tracking symptoms, identifying triggers, and noting responses to treatments, patients provide their healthcare providers with valuable information that can guide decision-making.

Next, dietary adjustments should be personalized based on symptom patterns. While general advice includes avoiding spicy foods, caffeine, alcohol, and large meals, individual responses vary. Patients may benefit from working with a registered dietitian to develop a meal plan that minimizes reflux and also addresses bloating, irregular bowel movements, or cramping. In cases of IBS overlap, a temporary low FODMAP trial may yield useful insights.

Stress management is another critical component. Patients are encouraged to explore techniques such as meditation, guided imagery, yoga, or even therapy to reduce the impact of stress on the digestive system. These practices not only support symptom control but also promote overall well-being and emotional resilience.

In terms of medical therapy, patients should work with their providers to optimize acid suppression, evaluate the need for motility agents, and consider adjunct therapies as appropriate. Those who do not respond to first-line treatments may require further evaluation through testing such as upper endoscopy, pH impedance monitoring, or gastric emptying studies to clarify the nature of their condition.

Finally, lifestyle interventions like regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and quitting smoking can have a profound effect on both GERD and broader digestive function. Even small changes—like elevating the head of the bed or waiting two to three hours after meals before lying down—can make a meaningful difference in symptom control.

A well-rounded approach acknowledges the individual nature of digestive disorders and avoids overly narrow diagnoses. By addressing GERD and its possible role in lower abdominal pain through a multifaceted lens, patients can achieve more sustainable relief and a better quality of life.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Understanding GERD, Lower Abdominal Pain, and Digestive Complexity

Can GERD cause lower abdominal pain during physical activity or exercise?

Yes, GERD can indirectly contribute to lower abdominal pain during physical activity, particularly in individuals with compromised gastrointestinal motility. When engaging in intense exercise, intra-abdominal pressure naturally increases, which can exacerbate acid reflux episodes. This pressure may not only trigger traditional symptoms like heartburn but also cause bloating and discomfort that extend into the lower abdomen. Additionally, individuals with acid reflux who perform abdominal-strengthening exercises or high-impact routines may unknowingly irritate already inflamed tissues or nerves, further intensifying pain. To reduce such symptoms, it’s beneficial to avoid eating two to three hours before exercising and to focus on upright, low-impact movements such as walking, which supports digestion and minimizes reflux-related pressure.

Understanding the Nervous System’s Role: Can GERD Cause Lower Abdominal Pain Through Neural Pathways?

Emerging research indicates that the nervous system, particularly the vagus nerve, may contribute to the perception that GERD is causing lower abdominal pain. The vagus nerve serves as a communication highway between the brain and multiple digestive organs, meaning that stimulation in one area can result in perceived sensations elsewhere. In GERD patients, overstimulation of the vagus nerve by acid in the esophagus can result in sensations of pain or pressure in the lower abdominal region. This is not due to acid physically traveling downward but rather a form of referred pain. Central sensitization may also play a role, where repeated reflux episodes create a heightened sensitivity to pain signals throughout the digestive system, including those felt lower in the abdomen.

What is the connection between acid reflux right side pain and sleeping positions?

Acid reflux right side pain often becomes more noticeable at night, and sleep posture plays a significant role in its severity. Lying on the right side has been shown to relax the lower esophageal sphincter more than the left side, making it easier for acid to escape into the esophagus. This not only intensifies upper stomach pain burning sensations but can also result in discomfort that radiates across the right flank or into the lower abdomen. Switching to left-side sleeping may significantly reduce the frequency and intensity of acid reflux symptoms by leveraging gravity to keep stomach acid away from the esophagus. Additionally, elevating the head of the bed by 6–8 inches can further aid in reducing nighttime reflux and its associated abdominal discomfort.

Can GERD cause abdominal pain that mimics gynecological conditions in women?

Absolutely. GERD and lower abdominal pain can sometimes overlap with symptoms commonly attributed to gynecological disorders, especially in women. For instance, bloating, cramping, and pelvic discomfort triggered by gastrointestinal dysmotility or inflammation can mimic menstrual-related pain or endometriosis. Because the pelvic cavity houses both digestive and reproductive organs, pain signals from one system can be misinterpreted as coming from another. This makes differential diagnosis essential. Women experiencing cyclic lower abdominal pain alongside reflux symptoms should consider both gastrointestinal and gynecological evaluations to ensure accurate treatment and avoid unnecessary interventions.

Can stress-induced reflux lead to persistent lower abdominal symptoms?

Yes, stress is a major exacerbating factor for GERD and can indirectly worsen symptoms experienced in the lower abdomen. Chronic stress disrupts the normal function of the gut-brain axis, leading to increased acid production, reduced gastric emptying, and heightened visceral sensitivity. This combination may cause not only upper stomach pain GERD typically produces but also contribute to bloating, irregular bowel habits, and cramping in the lower gastrointestinal tract. Mind-body interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy, guided breathing, and progressive muscle relaxation have been shown to reduce both reflux episodes and lower abdominal pain in patients with dual diagnoses. Managing stress is therefore not just a psychological concern—it’s an integral part of digestive wellness.

How do delayed gastric emptying and GERD together create symptoms in the lower abdomen?

Delayed gastric emptying, or gastroparesis, is a condition that slows down the movement of food from the stomach to the small intestine and often coexists with GERD. When this process is impaired, the accumulation of food and acid increases intragastric pressure, worsening reflux and contributing to bloating and cramping that extend into the lower abdomen. Over time, this pressure imbalance can affect downstream digestive processes, leading to constipation or gas pains. Patients with upper stomach pain GERD often report these coexisting symptoms, which are not purely localized but diffuse in nature. Treating delayed gastric emptying with dietary adjustments like low-fiber, low-fat meals and, in some cases, with prokinetic agents can significantly reduce both reflux and lower abdominal pain.

How can GERD cause lower abdominal pain in people with a history of abdominal surgeries?

In individuals with previous abdominal surgeries, scar tissue (adhesions) or altered anatomy may predispose them to gastrointestinal motility issues that worsen GERD and its associated symptoms. These changes can restrict normal digestive flow, leading to increased intra-abdominal pressure that aggravates reflux. The combination of altered motility and heightened sensitivity can result in symptoms that mimic or actually include lower abdominal pain. For instance, someone who has had bowel resection may experience slow transit times, which, when combined with GERD, creates a double burden on digestive regulation. Personalized management involving post-surgical dietary plans, physical therapy to reduce adhesions, and reflux control may help alleviate such compounded symptoms.

Could certain medications for GERD contribute to lower abdominal discomfort?

Yes, while medications like proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 blockers are effective in controlling upper stomach pain GERD causes, they are not without side effects that may affect the lower digestive tract. Long-term use of acid-suppressing drugs can alter the gut microbiome, leading to changes in digestion and nutrient absorption. This microbial imbalance may result in symptoms such as bloating, constipation, or even small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which can manifest as lower abdominal discomfort. Additionally, some patients report that PPIs exacerbate feelings of fullness or slow gastric motility. It’s important to regularly review medication regimens with a healthcare provider to ensure benefits outweigh potential downstream gastrointestinal effects.

Can GERD be confused with appendicitis or other acute abdominal conditions?

In some cases, GERD and lower abdominal pain may overlap with symptoms typical of acute conditions like appendicitis, particularly when pain radiates or is poorly localized. Although appendicitis usually presents with sharp, localized pain in the lower right abdomen, early stages may feel like generalized abdominal discomfort, especially in individuals with heightened visceral sensitivity. GERD-related discomfort may similarly present as diffuse or right-sided pain, especially in those who experience acid reflux right side pain due to posture or nerve involvement. However, acute symptoms such as fever, nausea, rebound tenderness, and rapid escalation of pain suggest a surgical rather than gastrointestinal origin. A timely diagnostic workup, including imaging and blood tests, is essential to differentiate between these conditions and avoid mismanagement.

Managing Digestive Complexity: Can GERD Cause Lower Abdominal Pain in IBS Patients?

Yes, and this relationship is more common than many realize. Individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are more likely to experience GERD and lower abdominal pain simultaneously due to shared mechanisms such as dysbiosis, altered motility, and heightened sensitivity in the digestive tract. In fact, nearly half of IBS patients report symptoms consistent with acid reflux. When both conditions co-occur, they tend to amplify each other, leading to a more persistent and diffuse pain experience that includes upper stomach pain burning as well as cramping in the lower abdomen. Addressing both issues simultaneously—with strategies like a low FODMAP diet, neuromodulators, and behavioral therapy—often yields better results than treating GERD and IBS in isolation. Understanding that these are not mutually exclusive disorders is crucial for long-term symptom management and quality of life improvement.

A Final Word: Why Recognizing the GERD-Lower Abdominal Pain Link Matters

In conclusion, the question—can GERD cause lower abdominal pain—deserves thoughtful consideration, particularly in light of what we now know about the interconnected nature of the digestive system. While GERD is classically defined by upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation, its influence often extends beyond the esophagus. Emerging evidence suggests that GERD may play a role in generating or exacerbating lower abdominal discomfort through mechanisms such as delayed gastric emptying, visceral hypersensitivity, systemic inflammation, and overlapping functional disorders like IBS.

Recognizing this broader symptom profile is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. Too often, patients with atypical symptoms are misdiagnosed or receive fragmented care that addresses only part of the problem. By embracing a more comprehensive understanding of GERD’s impact, healthcare providers can develop better-informed strategies that consider the full spectrum of digestive health.

For patients, awareness is power. Understanding how lifestyle, diet, stress, and coexisting conditions may contribute to GERD and lower abdominal symptoms empowers individuals to take meaningful action. Whether through dietary modification, stress reduction, or medical management, those who acknowledge the multifactorial nature of their symptoms are better positioned to find lasting relief.

As the field of gastroenterology continues to evolve, future research will likely offer even more nuanced insights into the relationship between reflux disease and lower abdominal discomfort. Until then, patients and providers alike benefit from staying curious, open-minded, and collaborative in their approach to digestive wellness. GERD is more than a condition of the esophagus—it’s a dynamic component of gastrointestinal health that may influence symptoms in surprising ways, including those felt in the lower abdomen.

By fostering a deeper, evidence-based understanding of GERD and its far-reaching effects, we move closer to a model of care that is both scientifically rigorous and deeply compassionate—one that honors the complexity of the human body and the lived experience of those navigating chronic digestive disorders.