For decades, dietary fat was demonized as the chief culprit in weight gain, heart disease, and a host of metabolic disorders. From the low-fat craze of the 1980s to the rise of fat-free everything on supermarket shelves, public health messaging long echoed the idea that consuming fat directly translated to becoming fat. But modern nutrition science has evolved, and today, researchers are unraveling more nuanced insights about the role of dietary fat in our bodies. This evolving landscape raises an important question: does eating fat make you fat, or is the truth far more complex than conventional wisdom once suggested?

You may also like: Macronutrients vs Micronutrients: What the Simple Definition of Macronutrients Reveals About Your Diet and Health

Recent research in nutritional science challenges old assumptions and invites us to re-examine the physiological impact of fat intake, the types of fat consumed, and the broader context of total dietary patterns. Understanding whether high fat foods turn into fat in the body involves more than simply tracking calories; it requires a deeper look into metabolism, hormonal responses, and even genetic predispositions. This article explores what the latest science reveals about the connection between dietary fat and body weight, shedding light on whether fat is friend or foe in the pursuit of long-term health and wellness.

Understanding the Basics: What Is Dietary Fat?

Dietary fat is one of the three essential macronutrients, alongside carbohydrates and protein. It serves vital functions in the human body, including energy storage, hormone production, nutrient absorption, and cell membrane integrity. Fat is also essential for absorbing fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K. Despite these critical roles, fat has historically been stigmatized due to its high caloric density—providing nine calories per gram compared to four calories per gram from protein or carbohydrates.

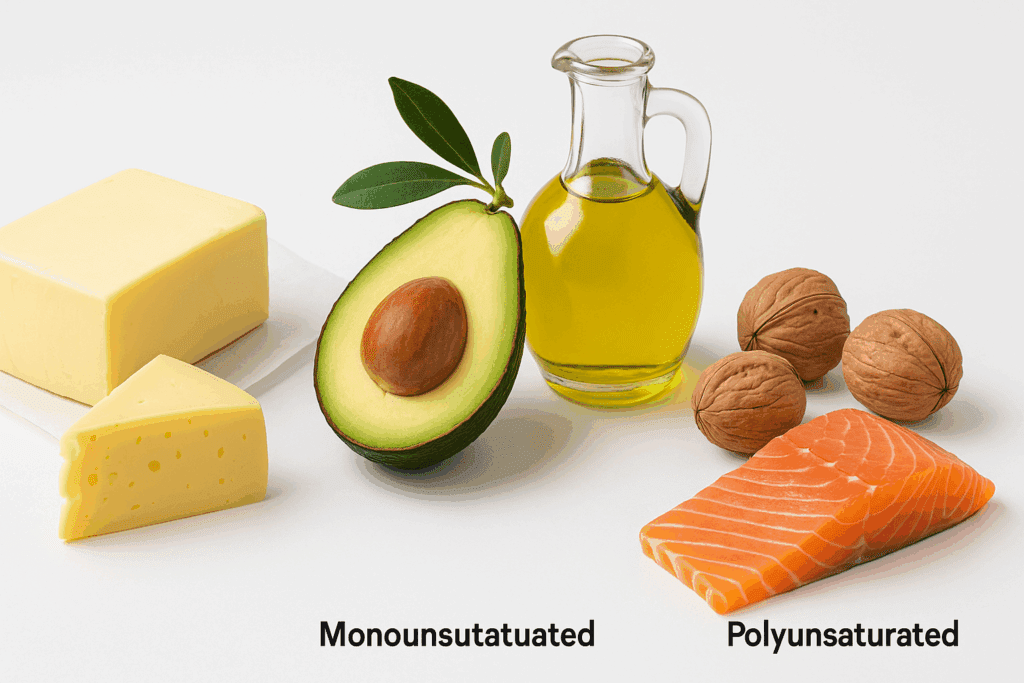

The negative perception of fat can be traced back to early epidemiological studies, which observed correlations between high fat consumption and elevated cholesterol levels. These observations, while influential, failed to account for the variety of fat types and their distinct effects. Saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, and polyunsaturated fat behave differently in the body. More recently, trans fats have been identified as particularly harmful, contributing to inflammation and cardiovascular disease.

To understand whether eating fat makes you fat, it is crucial to differentiate between these fat subtypes. Not all fats are created equal, and lumping them together under a single label can lead to misleading conclusions. Furthermore, the context in which fats are consumed—such as with fiber, protein, or refined carbohydrates—greatly influences how the body processes and stores them.

Revisiting the Low-Fat Diet Era: What Went Wrong?

During the latter half of the 20th century, public health authorities aggressively promoted low-fat diets to combat rising rates of heart disease and obesity. Food manufacturers responded by flooding the market with fat-free and low-fat alternatives, often laden with sugar, refined grains, and artificial additives to compensate for the loss of flavor and texture. Ironically, this shift coincided with surging rates of obesity and metabolic disease.

The assumption that fat inherently caused fat gain overlooked the complex hormonal interactions triggered by macronutrients. For instance, insulin plays a major role in fat storage, and high-carbohydrate, low-fat diets tend to elevate insulin levels more dramatically than balanced or high-fat diets. By focusing solely on fat reduction without considering the broader metabolic consequences, many well-intentioned diets failed to achieve their intended outcomes.

Several long-term studies have since questioned the efficacy of low-fat diets for weight loss and metabolic health. Notably, randomized controlled trials have found that moderate to high-fat diets—particularly those emphasizing unsaturated fats—can be just as effective, if not more so, for sustained weight loss and cardiometabolic improvement. These findings challenge the idea that eating fat makes you fat and underscore the need for individualized, evidence-based dietary strategies.

Metabolism and Fat Storage: Do High Fat Foods Turn Into Fat?

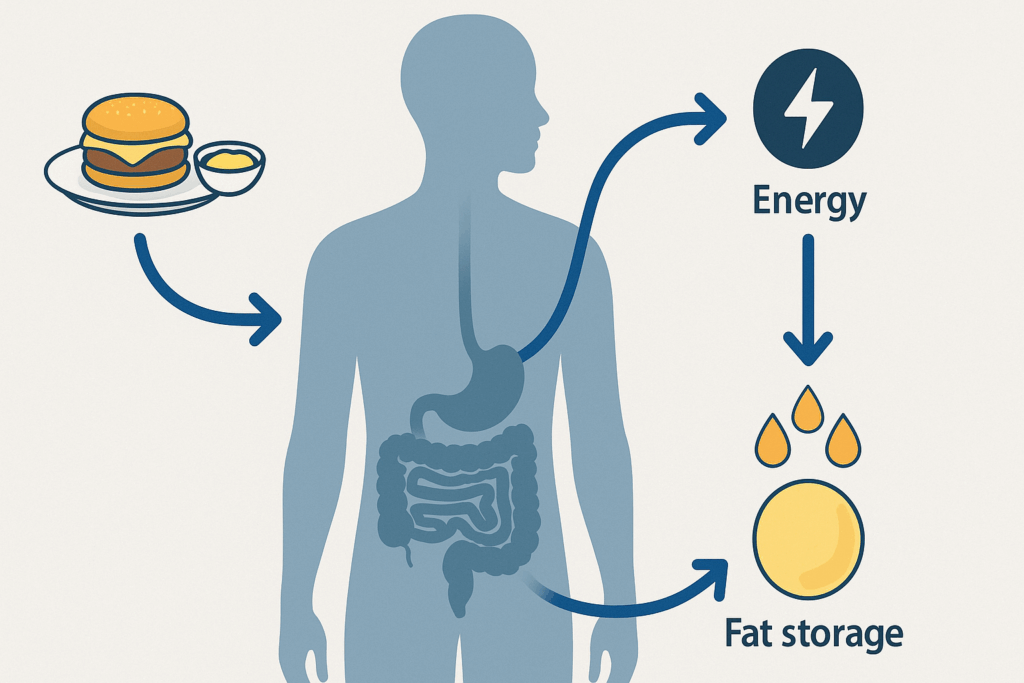

A key question in the debate is whether high fat foods turn into fat once consumed. While it’s true that dietary fat is easily stored in adipose tissue when in caloric surplus, the body’s metabolic processes are far more dynamic. Fat, carbohydrate, and protein are metabolized differently, and the body continually adjusts based on energy needs, hormone signals, and nutrient availability.

When you consume dietary fat, it is broken down into fatty acids and glycerol, absorbed through the intestines, and transported via lipoproteins throughout the body. These fatty acids can be used immediately for energy, stored for future use, or incorporated into cell membranes. Contrary to the simplistic notion that dietary fat turns directly into body fat, the process involves a complex interplay of metabolic pathways. For example, excess carbohydrates can also be converted into fat through de novo lipogenesis, a process that is metabolically costly but increasingly common in modern high-sugar diets.

Interestingly, the thermic effect of food—the amount of energy required to digest and metabolize nutrients—is lower for fat compared to protein and carbohydrates. This means fat is more efficiently stored when in caloric surplus. However, efficiency alone does not determine whether fat leads to weight gain. Context matters: in a calorie-balanced or calorie-restricted diet, high fat foods do not necessarily contribute to fat accumulation.

The Role of Hormones and Satiety in Fat Consumption

Another critical piece of the puzzle involves hormones that regulate hunger, fullness, and fat storage. Dietary fat has been shown to influence key hormones like leptin, ghrelin, insulin, and cholecystokinin (CCK), all of which contribute to appetite regulation and metabolic health. High fat foods, particularly those rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, often promote greater satiety compared to low-fat, high-carbohydrate meals.

When satiety is improved, people are more likely to consume fewer calories overall, which supports weight management and metabolic regulation. In this way, eating fat does not inherently make you fat—it may actually help reduce overeating by enhancing feelings of fullness and satisfaction. In contrast, many ultra-processed low-fat products may trigger the opposite effect: rapid spikes in blood sugar, followed by energy crashes and cravings.

Hormonal responses also vary by individual, depending on genetics, age, activity level, and existing health conditions. This variability underscores why some individuals thrive on higher fat diets while others do not. Ultimately, tailoring fat intake to individual needs and emphasizing fat quality over quantity can yield more favorable outcomes than one-size-fits-all recommendations.

Dietary Fat and Weight Loss: What the Evidence Shows

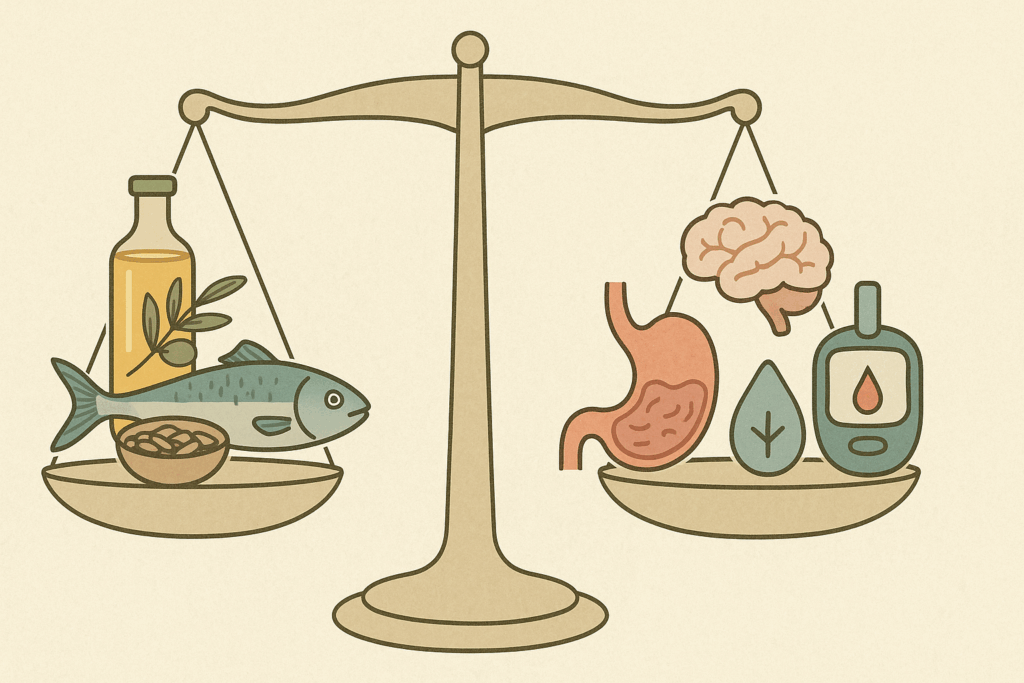

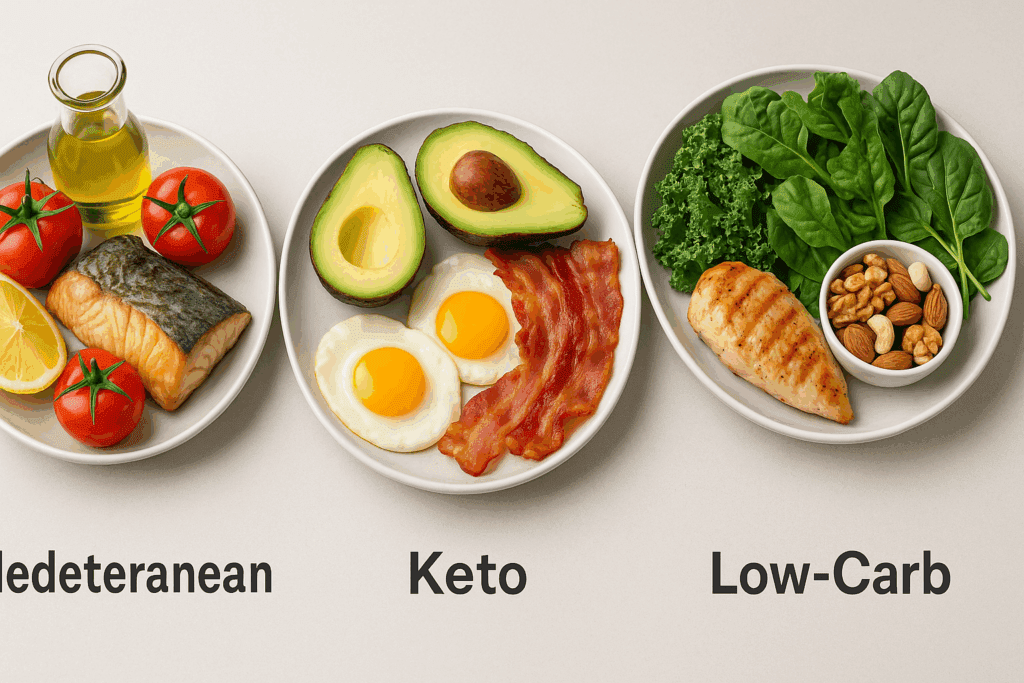

Numerous clinical trials have examined the effects of dietary fat on body weight, with some surprising results. The Mediterranean diet, which is relatively high in fat from sources like olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish, has consistently been associated with lower rates of obesity and improved metabolic outcomes. Similarly, ketogenic and low-carbohydrate diets, which are high in fat and extremely low in carbs, have demonstrated effectiveness for weight loss, blood sugar control, and appetite suppression.

These findings appear to contradict the idea that eating fat makes you fat. Instead, they suggest that the body can efficiently utilize fat for energy when carbohydrate intake is minimized and overall caloric intake is controlled. Moreover, participants on higher-fat diets often report greater dietary satisfaction and adherence, both of which are essential for long-term success.

Of course, no diet is universally effective, and some individuals may not respond well to high-fat regimens. Factors such as gallbladder function, lipid profiles, and insulin sensitivity must be considered when designing personalized nutrition plans. Nonetheless, the research clearly indicates that high fat foods do not automatically lead to weight gain and can, in many cases, support healthier body composition when part of a balanced, nutrient-dense diet.

Quality Over Quantity: Why the Type of Fat Matters

One of the most important lessons emerging from recent studies is that not all fats affect the body in the same way. While trans fats have been unequivocally linked to increased inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and insulin resistance, other fats—particularly omega-3 fatty acids and monounsaturated fats—offer protective benefits. These healthier fats are found in foods like avocados, olive oil, nuts, seeds, and fatty fish.

Replacing refined carbohydrates with healthy fats has been shown to improve lipid profiles, reduce triglycerides, and support insulin sensitivity. In contrast, diets high in industrial seed oils and processed foods may contribute to chronic inflammation and poor metabolic health. When asking “do high fat foods turn into fat,” it’s critical to distinguish between a meal rich in omega-3s and one heavy in trans fats from fried or packaged foods.

Focusing on whole food sources of fat, such as eggs, olives, and wild-caught salmon, allows individuals to harness the health-promoting properties of fat without falling into the trap of overconsumption. Moreover, such choices align with dietary patterns that prioritize nutrient density, food quality, and long-term sustainability.

Debunking Common Myths About Fat and Weight Gain

Despite growing evidence to the contrary, many myths about fat and weight gain persist. One of the most common misconceptions is that eating fat automatically leads to fat storage, regardless of context. In truth, weight gain results from sustained caloric surplus, regardless of whether those calories come from fat, protein, or carbohydrates.

Another pervasive myth is that dietary fat clogs arteries and contributes directly to cardiovascular disease. While certain types of fat—particularly trans fats and excessive saturated fats—can be harmful, the relationship between dietary fat and heart health is far more nuanced. Multiple meta-analyses have found no consistent link between saturated fat and heart disease, prompting many experts to revise their recommendations in favor of a more balanced, individualized approach.

Finally, the idea that low-fat diets are the best path to weight loss has not held up under scrutiny. In practice, low-fat diets often lead to higher carbohydrate consumption, which may exacerbate insulin resistance and hunger in some individuals. Understanding the broader metabolic impact of different nutrients is essential for making informed dietary choices.

Practical Strategies for Including Healthy Fats in Your Diet

Incorporating healthy fats into your daily routine can be both enjoyable and beneficial. Rather than avoiding fat altogether, focus on choosing high-quality sources and pairing them with nutrient-dense, fiber-rich foods. For example, adding a handful of walnuts to a salad, drizzling extra virgin olive oil over roasted vegetables, or enjoying full-fat Greek yogurt with berries can enhance both flavor and satiety.

Meal planning can also help ensure a balanced intake of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. Aim for diversity by rotating different fat sources—such as flaxseeds, chia seeds, avocados, and fatty fish—to cover a wide range of essential fatty acids. Cooking methods matter, too: baking, steaming, and sautéing in healthy oils are preferable to deep frying or using processed margarine.

Importantly, listen to your body’s signals and adjust your fat intake based on how you feel. If high fat meals leave you sluggish or bloated, it may indicate a need to adjust portion sizes or fat sources. Conversely, if fat-rich meals improve energy levels and curb cravings, they may be a valuable component of your personalized nutrition strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions: Does Eating Fat Make You Fat?

1. Can eating fat actually support weight loss rather than cause weight gain?

Yes, in many cases, dietary fat can assist in weight loss when incorporated wisely into a balanced diet. Unlike carbohydrates, certain fats help stimulate hormones that promote satiety, which may lead to naturally reduced calorie intake throughout the day. When people ask, “does eating fat make you fat?” they often overlook how fat-rich meals can help curb cravings, particularly those triggered by high-sugar diets. Some clinical trials have shown that diets higher in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats may outperform low-fat diets for long-term weight loss. Thus, eating fat doesn’t necessarily make you fat—it depends on how the fat fits into your broader dietary and lifestyle context.

2. Why do some people gain weight even on high-fat, low-carb diets?

While high-fat, low-carb diets like keto are effective for many, they aren’t foolproof. Caloric intake still matters—consuming more calories than your body needs, even from fat, can lead to weight gain. The question “do high fat foods turn into fat” highlights a concern that’s rooted in energy balance, not just macronutrient composition. Also, some individuals metabolize fat differently due to genetic factors or medical conditions like hypothyroidism or insulin resistance. If your body doesn’t efficiently use fat for energy, fat storage may increase, which can lead to the impression that eating fat inherently makes you fat, though it’s more about how your body processes and utilizes nutrients overall.

3. Are there psychological reasons people believe eating fat causes fat gain?

Yes, much of the fear around dietary fat stems from decades of diet culture and misleading public health campaigns. Many consumers equate the word “fat” in food with fat on the body, creating a deeply ingrained association. The phrase “does fat make you fat” became a marketing narrative rather than a scientifically grounded statement. Moreover, fat has more calories per gram compared to carbs or protein, which further cemented the belief that it should be avoided. These psychological associations often override evidence-based guidance, even when newer research contradicts them.

4. How do different cooking methods influence whether fat leads to weight gain?

Cooking methods can dramatically alter the metabolic impact of dietary fat. For example, roasting vegetables in olive oil preserves the health benefits of unsaturated fats, while deep-frying the same vegetables in refined seed oils can introduce inflammatory compounds. This subtle distinction is crucial when asking, “do high fat foods turn into fat,” because the health outcomes of fat consumption are influenced not just by quantity but also by quality. Overcooked or reused oils may degrade into harmful byproducts, undermining the health value of the fat itself. Choosing fresh, stable oils and low-heat cooking methods can help minimize the risks associated with fat consumption.

5. Do cultural dietary patterns help explain why fat isn’t always linked to obesity?

Absolutely. Take the Mediterranean diet, for instance—it is rich in olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish, yet populations who follow this eating pattern tend to have lower rates of obesity and heart disease. This raises important questions about the assumption behind “does eating fat make you fat” and shows how lifestyle and food culture play major roles. Many cultures consume high fat foods but balance them with plant-based foods, physical activity, and low levels of processed sugar. It’s not just the fat, but the dietary environment it lives in, that influences body weight outcomes.

6. Can stress influence whether dietary fat contributes to weight gain?

Chronic stress alters hormone levels, especially cortisol, which can increase fat storage—particularly visceral fat. Interestingly, people under stress may metabolize nutrients differently, making it more likely that even moderate fat intake contributes to fat accumulation. This nuance is often lost in the simple question, “does fat make you fat,” when in fact, stress physiology may be a major player. Moreover, stress often leads to emotional eating or cravings for high-fat, high-sugar comfort foods, compounding the effect. Managing stress through mindfulness, sleep, and exercise may be just as important as monitoring fat intake when trying to prevent weight gain.

7. Are there certain times of day when eating fat is less likely to contribute to weight gain?

Emerging research in chrononutrition suggests that the timing of fat intake may influence how the body stores or burns it. Eating larger amounts of fat earlier in the day, when insulin sensitivity and metabolic rate are higher, may reduce the likelihood that the fat will be stored as body fat. This lends fresh perspective to the question, “do high fat foods turn into fat,” because it shows how timing and circadian rhythms play a role. Consuming most of your fat late at night, when metabolic rate slows, may promote storage over utilization. Planning fat consumption to align with your body’s natural rhythms may enhance fat oxidation and energy balance.

8. How does alcohol interact with dietary fat in terms of weight gain?

Alcohol metabolism takes precedence over fat oxidation in the liver, meaning when you consume alcohol with a high-fat meal, your body temporarily halts fat burning. This increases the likelihood that the fat will be stored, especially if caloric intake exceeds what your body can immediately use. While the phrase “does eating fat make you fat” simplifies the issue, the interaction between alcohol and dietary fat reveals a more complex metabolic story. Moreover, alcohol can lower inhibitions, leading to overeating or poor food choices, which indirectly contribute to weight gain. Moderation in alcohol intake can support better outcomes when including fat in your diet.

9. Are there long-term consequences of avoiding fat due to fear of gaining weight?

Yes, chronic avoidance of dietary fat can have unintended health consequences. Fat is essential for the production of hormones, brain health, and the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins. When people overly restrict fat based on the belief that “does fat make you fat,” they may experience hormonal imbalances, nutrient deficiencies, or mood disturbances. In extreme cases, fat avoidance can lead to disordered eating patterns and metabolic dysregulation. Long-term well-being requires a balanced intake of high-quality fats, and fear-driven dietary choices can undermine both mental and physical health.

10. What role will emerging nutrition science play in reframing how we view fat?

The next wave of nutrition science is focused on personalization, microbiome diversity, and gene-diet interactions. As we learn more about how individual responses to fat vary, the blanket assumption behind “does eating fat make you fat” will likely continue to erode. Wearable tech, AI-driven nutrition apps, and advanced blood biomarker testing are allowing for tailored recommendations that account for how each body uniquely processes fat. Furthermore, future dietary guidelines may shift toward promoting fat quality and metabolic flexibility, rather than fat reduction. In this evolving landscape, fat will be understood not as a universal threat, but as a modifiable tool for optimizing health based on personal physiology.

Final Thoughts: Does Fat Make You Fat, or Is It Time to Rethink the Narrative?

After examining decades of nutritional research, the answer to the question “does fat make you fat” is far more nuanced than traditional diet dogma would suggest. The reality is that fat, by itself, does not inherently lead to weight gain. Rather, it is the broader dietary pattern, total caloric intake, food quality, and individual metabolic response that determine whether weight is gained or lost.

The idea that high fat foods turn into fat is rooted in outdated models of nutrition that fail to account for hormonal regulation, satiety, and nutrient synergy. Today’s evidence indicates that healthy fats can play a central role in supporting weight loss, metabolic health, and overall well-being—particularly when they replace processed carbohydrates and are consumed as part of a balanced, whole-food diet.

Understanding the complex relationship between fat and body weight empowers individuals to make more informed decisions about their nutrition. It encourages a shift away from fear-based food avoidance toward a more thoughtful, evidence-based approach. Ultimately, eating fat does not make you fat—overeating, regardless of macronutrient composition, does. When dietary fat is consumed mindfully, from high-quality sources, and in the context of a health-supportive lifestyle, it can be an ally rather than an adversary in your journey toward optimal wellness.

Further Reading:

Does Eating Fat Contribute to Weight Gain? Debunking Myths

Five days of eating fatty foods can alter how your body’s muscle processes food, researchers find