Description

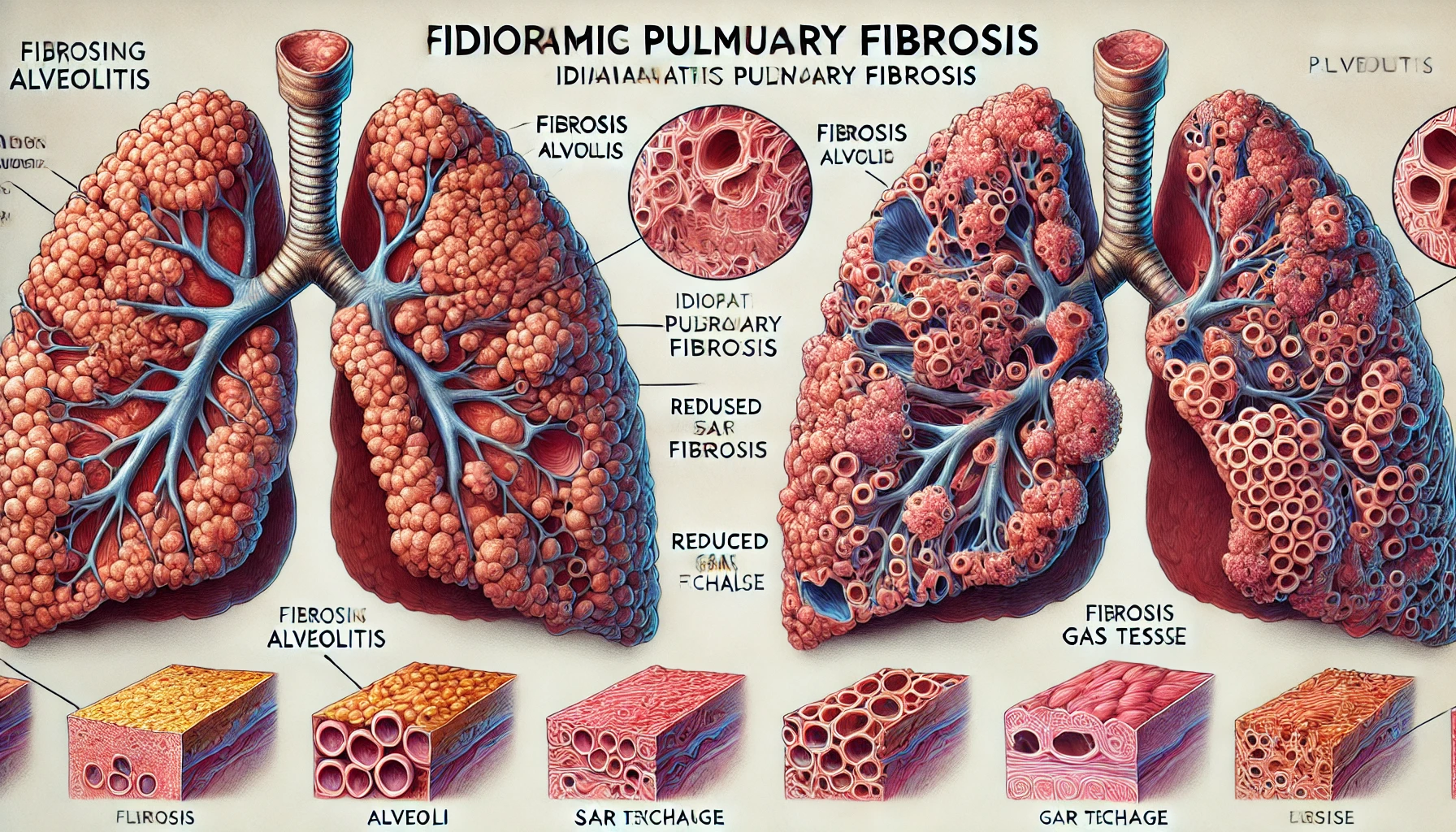

Fibrosing alveolitis, also called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), represents an interstitial lung disorder that is severe and progressive. It mostly affects the alveoli, which are the microscopic air sacs in the lungs that are in charge of gas exchange. Fibrous tissue forms as a result of this illness, which makes it difficult for the lungs to operate normally. IPF is a difficult illness to treat and has a big impact on the lives of those who have it.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, also known as fibrosing alveolitis, is a chronic and terminal lung disease that has the following characteristics:

Symptoms: Fibrosing alveolitis is frequently characterized by a chronic dry cough, dyspnea, exhaustion, chest pain, and inexplicable weight loss. The illness worsens symptoms as lung function deteriorates, and it advances slowly over time.

Progressive Scarring: Slow and permanent lung tissue scarring, which lowers lung compliance and function, is the defining feature of IPF. The overabundance of collagen deposits and tissue remodeling leads to this scarring or fibrosis.

Diagnosis: A combination of high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) images, clinical assessment, and occasionally lung biopsies are needed to diagnose IPF. Eliminating other possible causes of pulmonary fibrosis is a crucial diagnostic criterion.

You May Also Like:

Cold agglutinin disease: Description, Causes, and Treatment Protocol

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM): Description, Causes, and Treatment Protocol

Fibrosing alveolitis/Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): Description, Causes, and Treatment Protocol is an original (MedNewsPedia) article.

Possible Causes

Since the exact reason for fibrosing alveolitis is unidentified, it is categorized as “idiopathic.” However, several factors and theories have been presented:

Microbial Infections: According to certain research, persistent bacterial or viral infections may cause lung scarring by inciting an immunological reaction.

Aging: IPF seems more common in elderly people; the average age for onset is usually somewhere in the range of fifty to seventy years old.

Genetic Predisposition: An increasing amount of data points to a hereditary basis for IPF. An elevated risk of the disease has been linked to specific genetic variants.

Environmental Factors: IPF has been associated with exposure to industrial dangers and environmental contaminants, including wood dust, metal dust, and asbestos. Infections with viruses and smoking might also be factors.

Exacerbating and Mitigating Factors

Fibrosing alveolitis can worsen or improve in response to a variety of circumstances. These factors are listed below:

The exacerbating factors include:

Environmental Exposures: The development and aggravation of IPF may be attributed to exposure to hazardous substances in the workplace and environment. Lung injury can result from breathing in dust, fumes, and hazardous substances such as mold, metal dust, asbestos, and wood dust. It is imperative to minimize exposure to these drugs.

Smoking: One well-established trigger for IPF is cigarette smoking. If they smoke, those with IPF may see a faster deterioration in lung function.

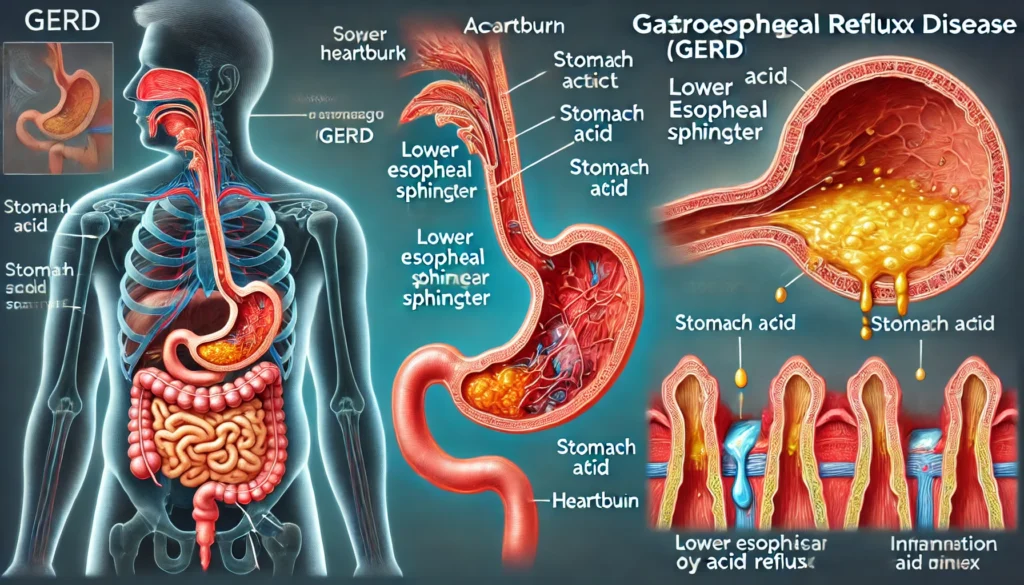

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Persistent acid reflux, which is frequently linked to GERD, can make IPF worse. It is thought that stomach acid might irritate and inflame the lungs as it enters.

Infections: Lung scarring may be exacerbated by persistent bacterial or viral infections, especially if they affect the respiratory system.

Aging: IPF has become more common in elderly people; the average age for initiation is usually 50 to 70 years old. Since lung tissue cannot renew or heal itself as one ages, aging itself constitutes a risk associated with the disease.

Comorbid Conditions: IPF can be made worse by pre-existing medical disorders like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

The mitigating factors include:

Occupational Safety: Protecting themselves against hazardous substances is something that workers in high-risk situations should do. To lessen the possibility of acquiring or aggravating IPF, this entails using protective gear and abiding by safety rules and regulations.

Smoking Cessation: One of the best strategies for reducing the rate at which IPF progresses and enhancing lung function is to stop smoking. As a key intervention, healthcare clinicians frequently stress the significance of quitting smoking.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Programs for pulmonary rehabilitation are designed to help people with IPF become more exercise-tolerant, acquire useful breathing skills, and improve their general physical function. These interventions have the potential to enhance symptom management and the standard of living.

Infection Prevention: The possibility of infections that could worsen IPF can be decreased by maintaining excellent cleanliness, receiving vaccinations against respiratory diseases including influenza and pneumonia, and seeking medical attention for respiratory illnesses whenever possible.

Dietary Habits and Weight Control: Reducing respiratory system strain and promoting general well-being can be accomplished through eating a balanced, healthy diet and maintaining a normal weight.

Lung Transplantation: This may be a lifesaver for those with significantly impaired lung function and advanced IPF. In certain circumstances, transplanting can greatly increase the standard of living and prolong survival, even though it is not a conventional mitigation method.

Advanced Therapies: Certain patients with IPF can qualify for cutting-edge treatments like lung transplants or experimental medications through clinical trials. Specialists and medical professionals should be consulted regarding these choices.

Comorbidity Management: To effectively manage IPF, underlying comorbid problems like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease must be addressed. Comorbidities under control might lessen the overall strain on the respiratory system and the body.

Standard Treatment Protocol

A multidisciplinary approach forms the basis of the conventional treatment strategy for fibrosing alveolitis. The following common treatment techniques are usually used in conjunction to control fibrosing alveolitis:

Pharmacological Interventions: These are as follows:

Corticosteroids

In certain circumstances, corticosteroids like prednisone are used to lessen lung inflammation. They aren’t regarded as a major treatment, though, and their long-term efficacy is disputed because of possible side effects.

Anti-fibrotic Medications

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) presently approves Pirfenidone and Nintedanib as anti-fibrotic medications for the management of IPF. These drugs have the potential to enhance lung function and slow the advancement of lung fibrosis.

Oxygen Therapy

Supplemental oxygen therapy may significantly boost oxygenation, reduce dyspnea, and improve day-to-day functioning in those with low blood oxygen levels.

Immunosuppressants

To lessen the immunological reaction that causes lung scarring, immunosuppressant drugs such as mycophenolate or azathioprine may be prescribed in specific circumstances. Usually saved for particular situations, these medications are seldom used frequently.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Programs for pulmonary rehabilitation are an essential part of managing IPF. These courses aim to teach breathing exercises, increase tolerance to physical exertion, and encourage physical activity. They can improve IPF patients’ standard of living.

Lung Transplantation: Lung transplants may be regarded as the last option in the advanced stages of IPF, whereby lung function deteriorates dramatically and the standard lifestyle is significantly compromised. The degree of a patient’s illness, overall health, and the availability of acceptable donors are among the elements that determine their eligibility for a lung transplant.

Supportive Care: An integral component of treating IPF is managing symptoms and consequences. This involves treating other comorbid disorders as well as using bronchodilators and cough suppressants.

Treatment Options

Although the conventional treatment protocol is the mainstay for managing IPF, patients and their medical professionals may also want to explore several supplementary therapy choices. These alternatives for supplemental treatment include:

Nutritional Supplements: These consist of the following:

Vitamin D

In general, healthy lung function depends on having enough vitamin D. If deficits are found in the blood, vitamin D supplementation might be advised.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Fish oil is a common source of omega-3 supplements, which have anti-inflammatory qualities and may help minimize lung inflammation. It is advised to keep an omega-3-rich, well-balanced diet.

Over-the-Counter Formulations: The possibility of the over-the-counter antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to decrease the course of IPF has been examined. Talking with a healthcare professional before using it is advised, as research on its effectiveness is still underway.

Natural Remedies: Breathlessness and coughing fits may be relieved by herbal teas made with ingredients like thyme, ginger, and honey. These treatments should not take the place of medical care; rather, they should be utilized as supplemental therapy.

Herbal Remedies: These include the following:

Curcuma longa (Turmeric)

The main ingredient in turmeric, curcumin, is well-known for having anti-inflammatory qualities and has been studied for possible advantages in treating lung inflammation.

Boswellia serrata

It is thought that this herbal supplement will lessen lung inflammation because of its anti-inflammatory qualities.

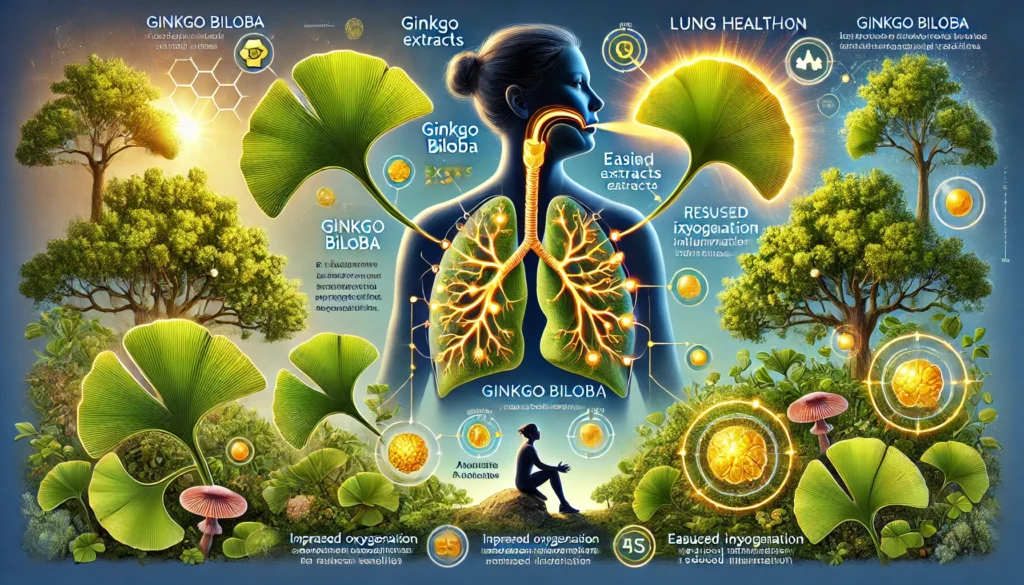

Ginkgo biloba

Herbal supplements like ginkgo biloba may also have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.

Traditional Chinese Medicine: To treat the underlying imbalances thought to contribute to IPF, practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine may employ a variety of medicines and therapies, including acupuncture and herbal formulations.

Breathing Techniques: A yogic breathing technique called pranayama can help people with IPF breathe easier, feel less anxious, and have better lung capacity.

Acupuncture: Through the use of tiny needles inserted into particular body locations, acupuncture has been reported by some patients to alleviate symptoms and enhance general health.

However, the important thing to remember is that each person responds differently to these adjunct therapies, therefore it’s important to use professional assistance when using them. Even while some people may benefit from adjunct therapies and experience an improvement in their quality of life, these treatments should not be viewed as stand-alone solutions but rather as complementary approaches to the overall care of fibrosing alveolitis.

Conclusion

Fibrosing alveolitis, or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), is a complex and progressive condition that significantly impacts lung function and quality of life. While its exact cause remains unknown, understanding the factors that exacerbate or mitigate the disease is crucial for effective management. A multidisciplinary approach, including pharmacological treatments, pulmonary rehabilitation, lifestyle modifications, and, in advanced cases, lung transplantation, forms the cornerstone of IPF management. Complementary therapies and nutritional support may also play a role in improving symptoms and enhancing overall well-being. Given the variability in how individuals respond to treatments, it is essential to work closely with healthcare professionals to create a tailored care plan that addresses both the physical and emotional challenges of living with IPF. With ongoing advancements in research, there is hope for improved therapeutic options and outcomes for those affected by this challenging condition.

Additional resources for further reference

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14598183

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-81591-z

https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/7/8/201

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physrev.00004.2016

Important Note: The information contained in this article is for general informational purposes only, and should not be construed as health or medical advice, nor is it intended to diagnose, prevent, treat, or cure any disease or health condition. Before embarking on any diet, fitness regimen, or program of nutritional supplementation, it is advisable to consult your healthcare professional in order to determine its safety and probable efficacy in terms of your individual state of health.

Regarding Nutritional Supplements Or Other Non-Prescription Health Products: If any nutritional supplements or other non-prescription health products are mentioned in the foregoing article, any claims or statements made about them have not been evaluated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and such nutritional supplements or other health products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.