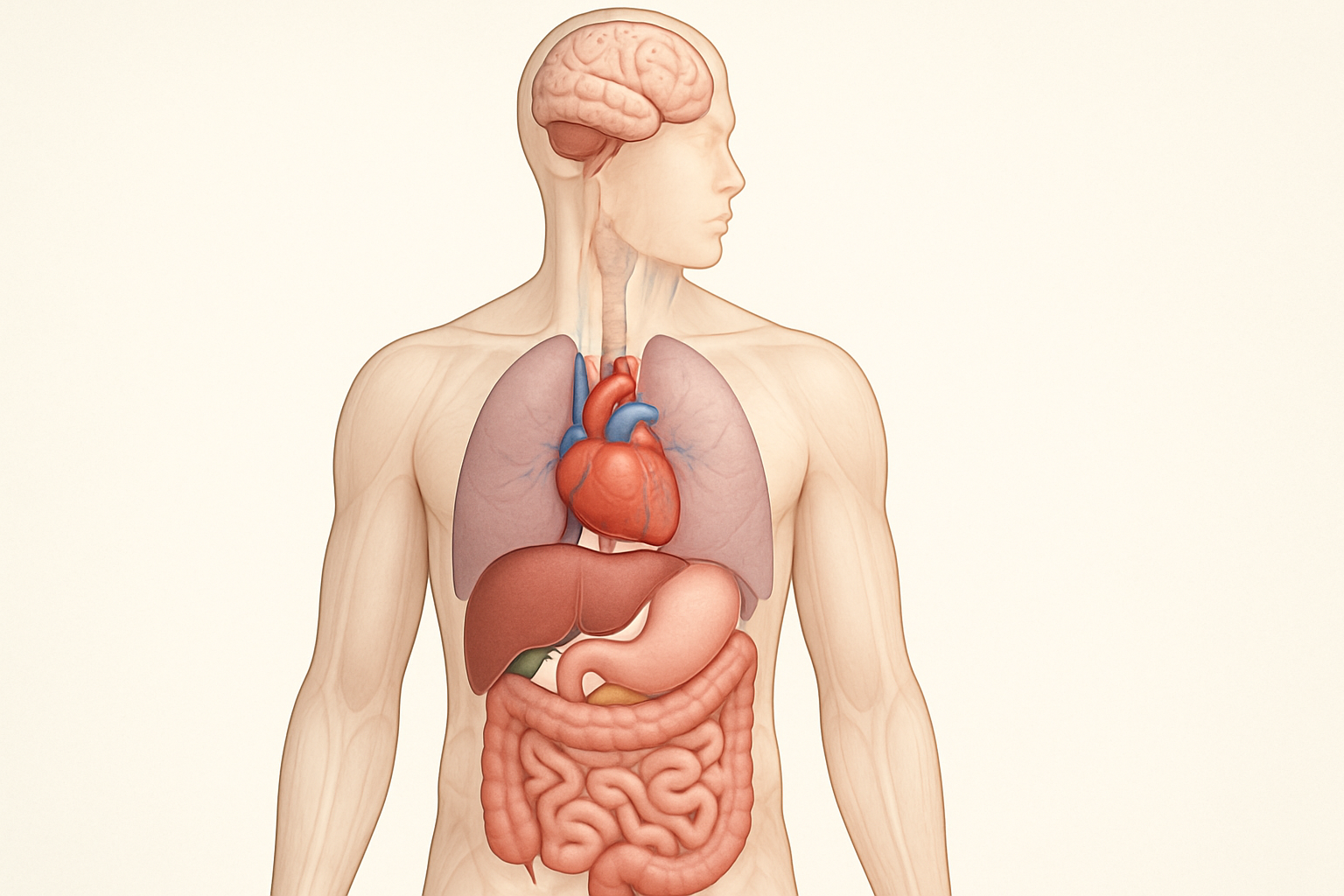

Understanding the inner workings of the human body goes far beyond academic interest; it can be a transformative tool for enhancing health and well-being. Specifically, knowledge of the location of organs and the anatomy of organs plays a pivotal role in making more informed dietary decisions and identifying the early signs of disease. While most people are aware that organs like the heart, liver, stomach, and intestines are crucial for life, few realize how a deeper comprehension of where these organs are situated and how they function can shape everyday health practices. This article delves into the critical intersection of anatomy, nutrition, and disease prevention, offering a detailed exploration of how anatomical literacy can empower individuals to live healthier lives.

You may also like: Macronutrients vs Micronutrients: What the Simple Definition of Macronutrients Reveals About Your Diet and Health

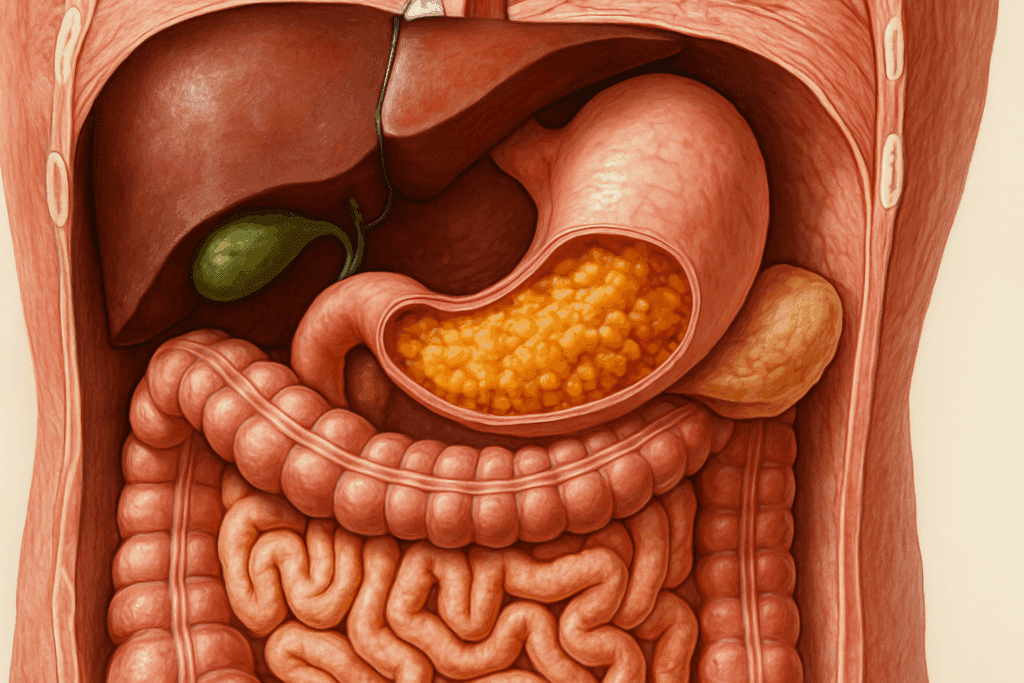

The Connection Between Organ Anatomy and Nutritional Efficiency

A foundational understanding of the anatomy of organs helps clarify how the body processes nutrients and eliminates waste. For example, knowing that the small intestine is the primary site for nutrient absorption helps explain why damage to this area—as seen in celiac disease or Crohn’s disease—can lead to serious nutritional deficiencies. The location of organs such as the stomach, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder also reveals how closely interlinked these systems are in digestive function. The stomach breaks down food with acid, the liver produces bile, the gallbladder stores it, and the pancreas releases enzymes that further digest fats and carbohydrates. When one of these organs is compromised, such as in cases of fatty liver disease or pancreatitis, digestion suffers. With a solid grasp of how these organs are situated and interact, people can make dietary choices that support rather than strain these systems.

For instance, diets rich in processed fats may overload the liver and pancreas, leading to long-term metabolic disturbances. On the other hand, high-fiber foods promote intestinal motility and support the colon’s function in waste elimination. Recognizing the anatomy of organs involved in digestion equips individuals with the knowledge to optimize their diets in alignment with how their bodies are anatomically designed to function. When dietary patterns are shaped by an understanding of the body’s internal structure, health outcomes can improve dramatically.

How Organ Location Influences Symptoms and Diet Choices

The location of organs within the body directly affects how symptoms manifest, and this knowledge can inform dietary adjustments that prevent complications. For example, discomfort in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen might indicate gallbladder issues, especially after a fatty meal. Those aware of the gallbladder’s role in fat digestion may recognize the need to reduce saturated fat intake to avoid triggering pain. Similarly, people experiencing bloating or cramping in the lower left abdomen might suspect colon involvement, potentially caused by diverticulitis or irritable bowel syndrome. This awareness encourages dietary changes, such as increasing soluble fiber or reducing FODMAP foods, which can alleviate symptoms.

The anatomy of organs also explains why certain food intolerances affect specific parts of the digestive tract. Lactose intolerance, for example, arises when the small intestine doesn’t produce enough lactase enzyme, leading to bloating and diarrhea. Knowing that the small intestine is located centrally in the abdomen can help individuals connect their symptoms to the organ responsible. When people understand the anatomical layout and functions of their digestive organs, they can more accurately pinpoint causes of discomfort and tailor their diets accordingly. This connection between organ location, symptom manifestation, and dietary modification is fundamental in preventing disease progression and improving quality of life.

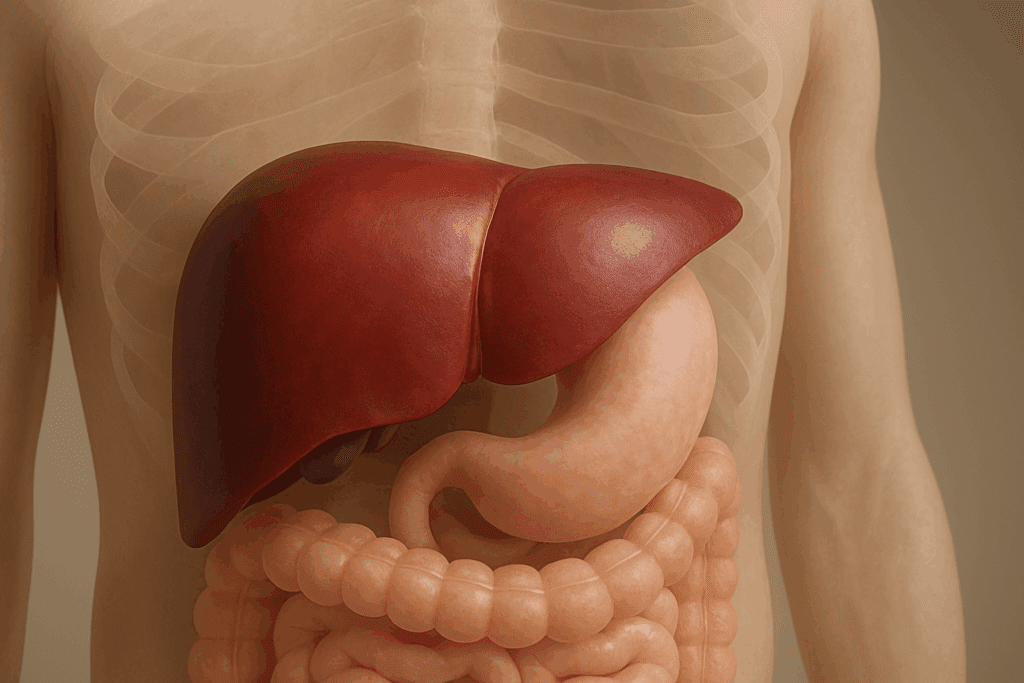

Optimizing Liver Health Through Anatomical Awareness

The liver is one of the most metabolically active organs in the body, responsible for detoxification, nutrient storage, and metabolism regulation. It sits in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen, tucked beneath the diaphragm and partially shielded by the ribcage. This strategic location allows the liver to receive nutrient-rich blood directly from the digestive tract via the portal vein, underscoring its central role in processing what we eat. A nuanced understanding of the liver’s anatomy reveals how lifestyle choices, especially diet, impact liver health.

For instance, excessive fructose consumption—often from sugary beverages—is metabolized in the liver, where it can be converted into fat. Over time, this can lead to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a condition increasingly common in Western societies. People who grasp the liver’s function and its anatomical proximity to other digestive organs are more likely to reduce sugar intake, increase antioxidant-rich foods like leafy greens and berries, and choose healthy fats that support liver function. The anatomy of organs such as the liver informs evidence-based dietary strategies that prevent chronic liver conditions. Such understanding emphasizes the importance of integrating nutritional care with anatomical knowledge.

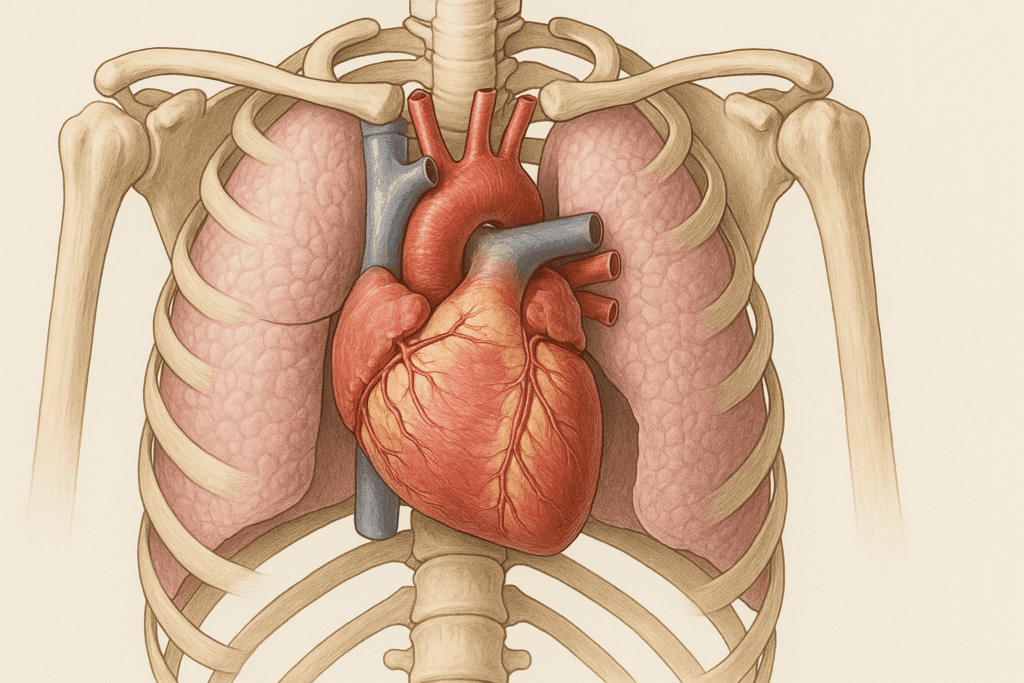

Heart Health and Organ Positioning in Cardiovascular Nutrition

The heart’s location in the thoracic cavity, slightly left of center and protected by the sternum and ribcage, plays a vital role in circulatory efficiency. It pumps oxygen-rich blood throughout the body and depends heavily on coronary circulation. Knowing the location of organs involved in the circulatory system enhances one’s ability to respond to early warning signs and modify dietary habits to protect heart health.

When individuals understand that arteries supplying the heart can become narrowed by plaque from high-cholesterol diets, they are better equipped to make dietary decisions that reduce saturated fat, trans fats, and processed foods. Nutritional awareness informed by anatomical insight reinforces the importance of heart-supportive foods, such as omega-3 fatty acids, nuts, seeds, and soluble fiber. Moreover, because the heart’s proximity to the lungs means respiratory health also affects cardiovascular performance, dietary strategies that reduce inflammation can benefit both systems. This integrated understanding of the location organs occupy and their anatomical relationships underlines the importance of holistic nutrition for cardiovascular prevention.

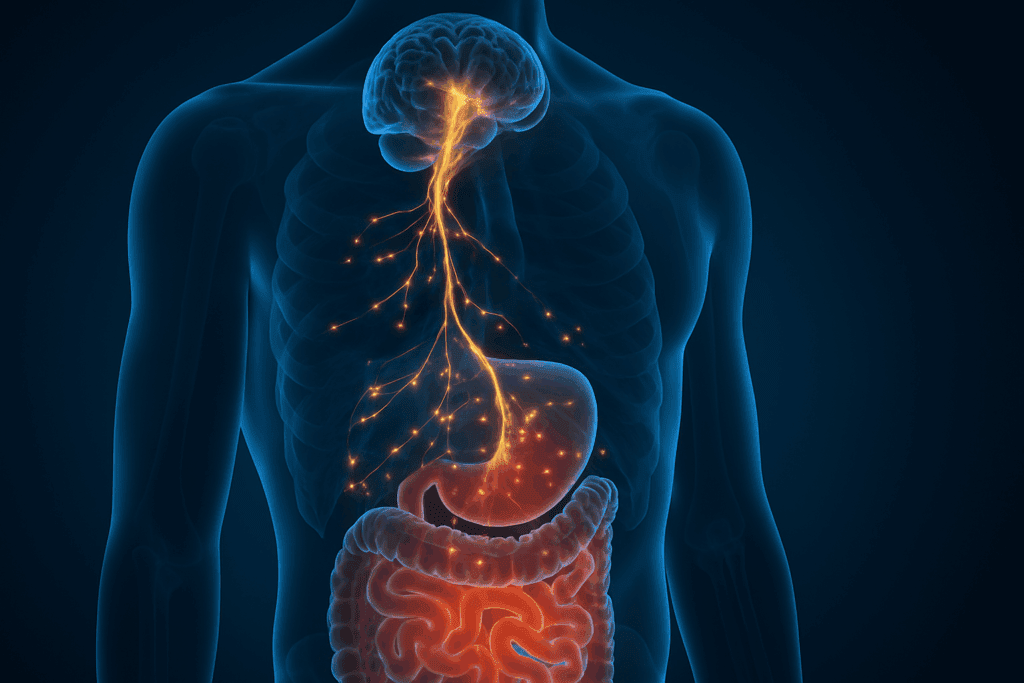

Gut-Brain Connection and the Central Role of Organ Placement

The gastrointestinal tract and the brain are more interconnected than previously imagined. The vagus nerve, which extends from the brainstem to organs in the chest and abdomen, plays a central role in mediating this communication. The anatomical pathway of the vagus nerve illustrates how emotional stress can influence digestion and how gut health can impact mental well-being. Understanding this connection through the lens of organ anatomy provides a deeper appreciation of how diet, gut microbiota, and psychological health intertwine.

The stomach and intestines are key players in producing neurotransmitters like serotonin, a significant proportion of which is synthesized in the gut. By comprehending where these organs are located and how they function, individuals can take actionable steps to support both gut and mental health through nutrition. Fermented foods, fiber-rich vegetables, and polyphenols from berries and green tea are all known to benefit the gut-brain axis. With a solid understanding of the anatomy of organs involved in digestion and neural communication, people can adopt diets that stabilize mood, reduce inflammation, and foster resilience against stress-related disorders. Organ location is not just a map of the body; it’s a guide to personalized, preventive nutrition.

Preventing Disease Through Targeted Nutritional Strategies

One of the most compelling reasons to learn the anatomy of organs is its power to facilitate disease prevention through targeted nutrition. The pancreas, situated behind the stomach and responsible for insulin production, is critical in blood sugar regulation. Diets high in refined carbohydrates and sugars overwork the pancreas, potentially leading to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Recognizing the organ’s function and anatomical location encourages dietary interventions early on, such as incorporating whole grains, legumes, and healthy fats to preserve insulin sensitivity.

Similarly, the colon, located in the lower abdomen, plays a vital role in processing waste and maintaining microbiome balance. Understanding the structure and function of this organ helps individuals realize the importance of fiber, hydration, and anti-inflammatory foods in preventing colorectal conditions. Knowledge of organ location can also guide preventive screenings—for instance, individuals aware of where the colon lies may be more alert to changes in bowel habits or discomfort that warrant medical attention. The anatomy of organs provides not only a physiological framework but a practical roadmap for dietary prevention strategies.

Integrating Organ Anatomy into Holistic Health Practices

Modern health approaches increasingly recognize the value of anatomical education in empowering patients to take control of their health. By integrating knowledge of organ location and function into routine health education, healthcare providers can promote more effective, individualized dietary strategies. People who understand their bodies from the inside out are more likely to comply with dietary guidelines, recognize the significance of symptoms, and adopt preventive behaviors.

This integrative approach also enhances collaboration between dietitians, physicians, and patients. For example, a nutritionist can explain how the kidneys—located in the back of the upper abdominal cavity—filter blood and regulate electrolyte balance, and thus why certain patients need to limit sodium or potassium. Such targeted dietary advice becomes more meaningful when rooted in anatomical understanding. As public interest in holistic wellness continues to rise, the anatomy of organs offers a bridge between scientific knowledge and practical action. The location organs occupy within the body becomes a blueprint for preventive care and dietary personalization.

Children and Adolescents: Teaching Anatomy for Lifelong Wellness

Introducing the basics of organ anatomy and location to children and adolescents can lay the groundwork for healthier choices throughout life. School-based health education that includes body systems and their nutritional needs can empower young people to understand why certain foods are encouraged and others discouraged. When students learn that the stomach is not just a container for food but a dynamic organ producing acid and enzymes, they gain respect for how their food choices affect digestion and energy levels.

This education can help dispel myths and reduce the influence of fad diets that often target teens. Teaching that the liver detoxifies harmful substances, and that this function can be impaired by excessive sugar or alcohol, promotes more responsible health behaviors. Understanding the anatomy of organs in early life leads to a generation that is better equipped to prevent disease and make informed dietary decisions. Equipping young people with this knowledge fosters lifelong health literacy and builds a culture of preventive wellness.

Navigating Nutrition in Aging with Anatomical Insight

As the body ages, the function and efficiency of various organs naturally decline. Anatomical understanding becomes even more important in this context, allowing older adults to adjust their diets to meet changing physiological needs. The stomach, for instance, may produce less acid with age, impairing the absorption of essential nutrients like vitamin B12, calcium, and iron. Knowledge of this change encourages older adults to include nutrient-dense foods or consider supplementation when appropriate.

Similarly, kidney function often diminishes with age, making it important to manage protein intake and hydration carefully. The kidneys’ position near the back of the abdominal cavity and their role in filtering waste are key considerations when planning diets for aging individuals. Recognizing these anatomical realities helps caregivers, clinicians, and older adults themselves tailor nutrition plans that prevent complications and maintain vitality. The location of organs and understanding their aging-related changes allow for proactive dietary strategies that preserve health and independence.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Organ Anatomy and Nutrition

1. How can understanding the location of organs influence hydration strategies in daily health?

Recognizing the location organs occupy can help guide more intentional hydration habits that support organ function. For instance, the kidneys—located toward the back of the lower ribcage—play a vital role in fluid balance and electrolyte regulation. Proper hydration ensures the kidneys can filter waste efficiently, especially when under strain from high-protein diets or certain medications. Additionally, staying hydrated supports blood volume, which aids the cardiovascular system in distributing oxygen and nutrients to organs like the brain and liver. When you understand both the anatomy of organs and their positioning, you’re better equipped to time your water intake strategically throughout the day, especially during high-output activities or in hot climates.

2. Are there psychological benefits tied to learning about organ anatomy and their locations?

Yes, there are growing studies linking anatomical literacy to reduced health anxiety and increased body confidence. When individuals grasp the location organs hold within their body and how each system functions, it can demystify symptoms and alleviate unnecessary fear. Rather than panicking over vague discomfort, people who understand the anatomy of organs are more likely to assess their condition calmly and seek appropriate care. This empowerment contributes to better health outcomes and a more proactive mindset. Furthermore, such knowledge may improve communication between patients and healthcare providers, strengthening shared decision-making in clinical settings.

3. How can athletes use knowledge of organ anatomy to enhance performance and recovery?

For athletes, knowing the location organs occupy can refine training and recovery strategies. For example, understanding where the liver and muscles intersect in metabolic activity helps athletes choose foods that support glycogen storage and detoxification post-exercise. The anatomy of organs also reveals how digestive transit times vary depending on food type and organ workload—knowledge that is essential when timing meals before endurance events. Proper fueling based on organ function, such as minimizing fat intake pre-run to reduce gastric distress, optimizes nutrient utilization and performance. Additionally, knowledge of spleen and cardiovascular placement can help athletes manage side stitches and heart rate variability with greater precision.

4. What role does anatomical knowledge play in managing chronic digestive conditions?

People living with chronic conditions like GERD, IBS, or IBD benefit immensely from understanding the specific location organs involved in their condition. Knowing that the lower esophageal sphincter controls acid reflux, for instance, informs meal timing and posture decisions. The anatomy of organs such as the colon and small intestine can also guide fiber choices—soluble versus insoluble—for managing flare-ups. Furthermore, people who understand their own gastrointestinal map can use positional therapy (e.g., lying on the left side to reduce heartburn) and identify patterns in symptoms that align with specific organ locations. This proactive management often leads to fewer emergency interventions and a higher quality of life.

5. Can anatomical awareness help prevent nutrient deficiencies in plant-based diets?

Absolutely. Individuals following vegetarian or vegan diets can use knowledge of the location organs and their functions to prevent specific deficiencies. The stomach’s role in protein breakdown and the small intestine’s role in iron and B12 absorption become especially critical. Plant-based eaters can support these organs by incorporating foods that aid digestion, such as fermented vegetables, and by combining iron-rich foods with vitamin C to boost absorption. Understanding the anatomy of organs also helps identify when supplementation is needed—such as calcium for bone health when parathyroid gland function is affected. With this insight, nutrient timing and bioavailability can be optimized for long-term well-being.

6. How can organ location and anatomy guide detoxification practices more safely?

Detox trends often promote unproven or even dangerous regimens, but a proper understanding of the anatomy of organs debunks many of these myths. The liver, which is centrally positioned under the ribcage, already performs natural detoxification without the need for extreme fasting or juice cleanses. Supporting the liver and kidneys with adequate protein, antioxidants, and hydration is far more effective than using herbal purgatives or diuretics. Awareness of where these organs are located and how they work allows for more science-based decisions when considering detox practices. It encourages moderation and consistency over drastic short-term methods, ultimately protecting long-term organ function.

7. What are the implications of anatomical knowledge in food allergy and intolerance management?

Food intolerances affect specific anatomical regions of the digestive system, and knowing the exact location organs affected helps tailor responses. For example, lactose intolerance stems from the small intestine, while histamine intolerance may involve enzyme interactions in both the intestines and liver. The anatomy of organs reveals where enzymes like lactase are active and where histamine degradation occurs, enabling more accurate dietary planning. Furthermore, understanding the immune response in relation to gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) deepens awareness of how food allergies differ from intolerances. A detailed grasp of organ location empowers patients to track reactions more precisely and avoid overly restrictive diets.

8. How does anatomical knowledge affect meal planning for people with limited digestive capacity?

Individuals with compromised digestion, such as those recovering from gastrointestinal surgery or dealing with motility disorders, can benefit greatly from understanding the anatomy of organs. Meal size, texture, and frequency can be tailored based on where digestion slows or stalls. For example, patients missing portions of the small intestine must eat nutrient-dense meals that compensate for absorption challenges. Knowing the location organs involved in fat digestion occupy—like the gallbladder or pancreas—can inform when and how to introduce dietary fats without causing distress. This anatomical perspective supports personalized nutrition that reduces symptom severity while maintaining adequate caloric intake.

9. Are there any emerging technologies that integrate organ location data with diet planning?

Yes, the rise of precision health platforms and wearable biosensors is beginning to integrate real-time feedback from internal organ systems into dietary recommendations. Some advanced imaging tools now map the location organs occupy and assess how structural differences affect nutrient processing, offering hyper-personalized nutrition profiles. There are also microbiome-based apps that evaluate digestive organ performance based on stool data and suggest meals accordingly. As this field grows, the anatomy of organs will play a foundational role in developing AI-driven diet systems that go beyond calorie counting. These innovations promise to bridge the gap between structural biology and functional nutrition like never before.

10. How can parents use anatomical education to foster better eating habits in children?

Introducing children to basic concepts of where their organs are and what they do can make nutrition more tangible and engaging. When kids understand that their stomach is not a “food bucket” but a working organ that signals fullness and digestion, they are more likely to eat mindfully. Visual aids and interactive activities that show the anatomy of organs help children grasp how their bodies respond to sugar, fiber, and protein. Teaching the location organs like the liver and intestines occupy opens conversations about how fruits, vegetables, and whole grains support those organs. Over time, this builds a sense of bodily respect and responsibility, laying the foundation for lifelong healthy habits.

Conclusion: Empowering Preventive Health Through Organ Anatomy and Diet

Ultimately, understanding the location of organs and the anatomy of organs is not just a matter of biological curiosity—it is a powerful, practical asset for preventive health. This anatomical insight allows individuals to interpret bodily signals more accurately, choose foods that support the specific needs of each organ, and recognize early signs of dysfunction before they escalate into chronic disease. From the digestive tract to the cardiovascular and endocrine systems, anatomical literacy enhances the precision and effectiveness of nutrition.

Moreover, this knowledge fosters a deeper respect for the body’s complexity and encourages intentional, evidence-based decisions about food and lifestyle. Whether managing heart health, supporting liver detoxification, or preserving gut balance, awareness of organ function and structure provides a science-backed pathway toward better wellness outcomes. As public health efforts increasingly shift toward prevention and education, promoting an understanding of the location organs occupy and the anatomy of organs will be essential for empowering individuals to take charge of their health through diet.

By embedding this awareness into everyday choices, people can transform the abstract concept of anatomy into a lived, beneficial practice—one that supports a healthier, more informed future for all.

Further Reading:

Review of all human body organs

Organs and organ systems in the human body