In recent months, medical experts and global health organizations have turned their attention to a new flu virus strain that has demonstrated unexpected patterns of transmission and virulence. The emergence of this strain has prompted renewed discussions about public health preparedness, vaccine efficacy, and the evolving nature of influenza viruses. As the influenza season intensifies and communities worldwide begin to report increasing cases, understanding the mechanisms and implications of the new flu virus is more than just a scientific concern—it is a public health imperative. Given how respiratory infections can rapidly spiral into seasonal epidemics or even pandemics, the need to remain informed has never been more urgent.

The term “new flu virus” is not used lightly. It denotes a mutated strain of influenza that either has not been observed previously in humans or exhibits genetic recombination sufficient to alter its behavior, resistance, or pathogenicity. These mutations can emerge through antigenic shift or drift, resulting in viruses that evade prior immunity in the population. Complicating matters further, the pace at which global travel and climate change influence viral spread adds another layer of complexity to managing these outbreaks. As such, staying protected requires not only vaccination but also a nuanced understanding of how flu viruses operate, adapt, and circumvent both medical and immune defenses.

What makes the current situation particularly concerning is the convergence of several risk factors. Firstly, the public’s pandemic fatigue has resulted in relaxed hygiene protocols, making viral transmission easier. Secondly, early data indicate that this new strain may present with atypical symptoms, leading to delayed detection and misdiagnosis. Thirdly, there are preliminary reports that suggest the virus may disproportionately affect certain demographics, such as young adults or individuals with pre-existing respiratory conditions. These factors combine to create a potentially volatile public health scenario that calls for a clear-eyed assessment of what is truly at stake.

The goal of this article is to provide a comprehensive, evidence-based exploration of the new flu virus, covering its origins, clinical features, transmission pathways, treatment options, and preventive strategies. This is not merely an academic exercise; the information here can empower individuals and communities to take informed steps to mitigate risk. In the pages ahead, we will explore what distinguishes this strain from more familiar influenza types, why traditional flu vaccines may or may not offer sufficient protection, and what signs and symptoms demand immediate medical attention. By understanding the full scope of this health threat, readers can navigate the current flu season with greater confidence and resilience.

Ultimately, knowledge is our first line of defense. While much remains to be discovered about the new flu virus, what we already know is enough to prompt heightened vigilance. Whether you are a healthcare provider, a concerned parent, or simply someone striving to stay healthy, the insights contained in this article are designed to help you remain informed, prepared, and protected.

You may also like: Essential Tips for Prevention from Flu and Other Common Respiratory Infections

What Sets the New Flu Virus Apart from Seasonal Influenza Strains

One of the most pressing questions surrounding any emerging influenza strain is what differentiates it from the typical viruses we encounter each flu season. While the core structure of influenza viruses remains relatively stable, minor genetic changes known as antigenic drift and major shifts in genetic material—antigenic shift—can produce viruses with significantly altered behavior. The new flu virus appears to have undergone several such genetic changes, allowing it to both escape existing immunity and spread more efficiently in certain populations. These molecular alterations can influence everything from the virus’s incubation period to the severity of its symptoms, challenging both public health systems and medical professionals.

Recent genomic analyses of the new strain reveal mutations in the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins, which play a crucial role in how the virus binds to and exits host cells. Such changes can diminish the effectiveness of existing vaccines that are tailored to older strains, raising questions about whether current immunization strategies are sufficient. Additionally, there is emerging evidence that the virus exhibits a broader host range, potentially jumping between species more easily than its predecessors. This zoonotic capability significantly increases the likelihood of unforeseen outbreaks, especially in regions with dense animal-human interaction.

Another characteristic of the new flu virus that has drawn attention is its atypical symptom profile. While traditional flu symptoms include fever, chills, sore throat, and muscle aches, some cases of the new virus have been marked by gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and abdominal discomfort, or neurological signs like dizziness and confusion. This variation can lead to delays in diagnosis, particularly in clinical settings that rely heavily on symptom checklists. It also underscores the importance of molecular testing, which can detect the virus even in the absence of classic respiratory symptoms.

Moreover, the virus seems to exhibit heightened transmissibility, possibly due to increased viral shedding or enhanced stability on surfaces and in aerosols. This makes containment especially difficult in high-traffic environments such as schools, workplaces, and public transportation systems. Unlike previous strains that required close contact for effective transmission, preliminary data suggest that the new flu virus may spread more readily through casual interactions, raising the bar for effective preventive measures.

Lastly, the new strain’s behavior in vulnerable populations adds another layer of complexity. Early surveillance reports have noted a spike in hospitalizations among younger adults and individuals without underlying conditions, a departure from the pattern seen in many previous influenza outbreaks where the elderly and immunocompromised bore the brunt of severe cases. This shift necessitates a reevaluation of who is considered “high risk” and calls for updated clinical guidelines to reflect the virus’s evolving impact profile.

Global Spread and Public Health Implications of the New Flu Virus

The global landscape of infectious disease transmission has changed dramatically over the last few decades, with rapid air travel and urbanization facilitating the swift spread of pathogens. The new flu virus is no exception. Within a few months of its identification, confirmed cases have been reported on multiple continents, including North America, Europe, and parts of Asia. This rapid spread underscores the interconnectedness of modern societies and the urgent need for global cooperation in tracking and managing influenza outbreaks.

One of the most alarming developments is the uneven surveillance and response capacity among nations. While countries with robust healthcare infrastructure have been able to sequence viral genomes and share data with international databases, many developing nations lack the tools necessary for early detection and reporting. This creates blind spots in the global epidemiological map, allowing the virus to spread undetected in certain regions before emerging in more closely monitored populations. As a result, it becomes difficult to model outbreak trajectories or allocate resources efficiently, hampering containment efforts.

Another layer of public health complexity lies in balancing pandemic preparedness with ongoing healthcare demands. In many countries, the healthcare system is still recovering from the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic. Resources are stretched thin, personnel are exhausted, and public trust in medical institutions is fragile. Introducing a new viral threat into this environment heightens the risk of system overload, particularly during peak flu season when hospital admissions typically surge. The concern is not just about beds and ventilators but about having enough diagnostic tools, antiviral medications, and trained staff to manage an influx of patients presenting with flu-like symptoms.

Government responses to the new flu virus have varied significantly, reflecting differences in political will, public health philosophy, and logistical capability. Some countries have issued updated guidelines for flu vaccination, incorporating available data on the new strain, while others have focused on non-pharmaceutical interventions like mask mandates and ventilation improvements. The World Health Organization has emphasized the importance of real-time data sharing and has urged member states to enhance their surveillance and reporting systems. These measures are essential, but they also depend heavily on public compliance and interagency coordination, both of which can be difficult to secure in practice.

At the community level, public health messaging has become a focal point of concern. With misinformation spreading rapidly on social media platforms, clear and consistent communication from trusted sources is more critical than ever. People need to know not only what the new flu virus is but how it affects them personally and what actions they can take to stay safe. Failure to communicate effectively can result in apathy or panic—both of which are detrimental to outbreak management. Thus, public education campaigns must strike a balance between urgency and reassurance, avoiding alarmist tones while clearly articulating the stakes involved.

Early Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of the New Flu Virus

Recognizing the early signs of infection is essential for effective treatment and containment of any viral illness, and the new flu virus presents unique diagnostic challenges. While some patients display the hallmark symptoms of influenza, including fever, dry cough, and fatigue, others may exhibit subtler or less typical signs. This variability in clinical presentation can delay diagnosis and increase the risk of transmission, especially in environments where people may attribute mild symptoms to common colds or seasonal allergies.

One distinguishing feature of the new flu virus appears to be its effect on the gastrointestinal system. Reports have surfaced of patients experiencing nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—symptoms more commonly associated with norovirus or foodborne illnesses. This overlap in symptomatology can mislead clinicians, particularly in outpatient settings where comprehensive testing may not be routine. Moreover, some patients have reported experiencing only mild respiratory symptoms initially, followed by a sudden escalation in severity, including shortness of breath and high fever, within a matter of days.

Neurological symptoms, though less common, have also been documented. These include headaches, dizziness, and in rare cases, temporary cognitive impairments such as confusion or memory lapses. While these signs are not exclusive to the new strain, their presence underscores the virus’s potential to affect multiple organ systems. In severe cases, complications such as viral pneumonia, myocarditis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have been observed, necessitating hospitalization and advanced medical care.

Another complicating factor is the variable incubation period. While traditional influenza strains typically have an incubation period of one to four days, preliminary data suggest that the new flu virus may incubate for up to a week before symptoms manifest. This extended window not only increases the likelihood of asymptomatic transmission but also challenges standard protocols for quarantine and contact tracing. People may unknowingly spread the virus to family members, coworkers, or strangers before realizing they are infected, thereby amplifying community transmission.

Because of these factors, early intervention is crucial. Individuals experiencing any combination of flu-like, gastrointestinal, or neurological symptoms—particularly during a time when influenza is going around—should seek medical advice promptly. Diagnostic testing, including rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, can help confirm the presence of the virus and guide treatment decisions. As healthcare providers become more familiar with the virus’s unique clinical footprint, diagnostic accuracy is expected to improve, but until then, a high index of suspicion remains vital.

Navigating Testing and Diagnosis Amid Rising Cases of the New Flu Virus

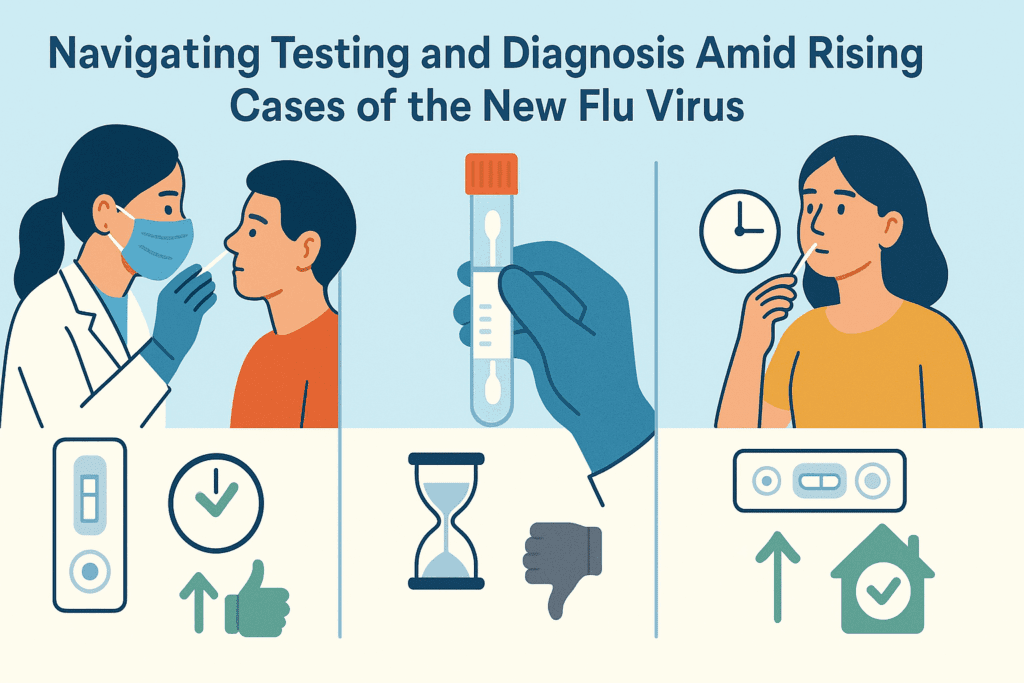

As cases continue to climb and more communities report outbreaks of the new flu virus, the importance of accurate and timely testing cannot be overstated. Early detection plays a crucial role not only in initiating effective treatment but also in implementing public health interventions that can reduce further transmission. However, diagnosing this virus poses distinct challenges due to its overlapping symptoms with other respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses, as well as the evolving nature of available testing technologies.

Rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) have long served as the first line of screening for influenza, offering results within minutes. Yet these tests have known limitations in sensitivity, particularly when detecting novel strains that may not be fully represented in existing assay libraries. As a result, many clinicians are shifting to molecular diagnostic tools, such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays, which offer higher specificity and sensitivity. RT-PCR tests can detect viral RNA even in cases with low viral load, making them ideal for identifying asymptomatic or early-stage infections.

Despite the advantages of molecular testing, logistical constraints remain. RT-PCR tests require specialized equipment, trained personnel, and longer turnaround times compared to RIDTs. In under-resourced regions or during periods of high demand, testing backlogs can delay diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, inconsistencies in test availability and reporting standards can lead to undercounting of cases, hindering efforts to understand the true scope of the outbreak. These gaps highlight the need for investment in diagnostic infrastructure and the development of point-of-care tests that combine speed with accuracy.

Clinicians are also grappling with a broader diagnostic dilemma: distinguishing the new flu virus from other respiratory pathogens, including COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and adenovirus. Co-infection with multiple viruses is increasingly common, especially among pediatric and elderly populations. As such, comprehensive respiratory panels that test for a wide array of pathogens are becoming more valuable, allowing healthcare providers to rule out or confirm the presence of the new flu virus alongside other possibilities.

Beyond clinical settings, at-home testing is gaining traction as a tool for early detection and self-isolation. Several biotechnology companies are working to develop flu-specific home test kits that can detect the new strain with reasonable accuracy. While promising, these kits must undergo rigorous evaluation to ensure their reliability, especially when used without clinical oversight. Public education on the proper use and interpretation of home testing is equally important to prevent false reassurance or unwarranted panic.

Given the growing number of reports indicating influenza going around in various regions, accurate diagnosis remains the linchpin of effective outbreak response. Testing protocols must be adaptable to evolving viral characteristics, and public health systems must prioritize accessibility, transparency, and coordination to ensure timely identification and containment of new cases.

The Role of Vaccines: How Prepared Are We for the New Flu Virus?

Vaccination has long been the cornerstone of influenza prevention, and the emergence of the new flu virus raises urgent questions about the efficacy and adaptability of current immunization strategies. Seasonal flu vaccines are developed months in advance, based on predictions of which strains are likely to dominate. However, when a novel strain emerges unexpectedly or mutates beyond recognition, the protective efficacy of existing vaccines may be significantly compromised.

Preliminary studies suggest that the current season’s vaccine offers only partial protection against the new strain. While it may still reduce the severity of illness and lower the risk of complications, breakthrough infections have been reported even among vaccinated individuals. This underscores the need for updated vaccines that specifically target the genetic makeup of the new flu virus. The process of developing and distributing such vaccines is complex, involving months of research, production, and regulatory approval. Nevertheless, accelerated vaccine platforms—such as those using mRNA technology—offer a promising path forward, potentially reducing the time needed to produce a targeted vaccine.

Another consideration is the vaccine uptake rate. Public trust in vaccines has declined in certain segments of the population due to misinformation, politicization, and residual skepticism from the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing these concerns requires transparent communication from public health officials, as well as targeted outreach programs that consider cultural, socioeconomic, and logistical barriers. Ensuring equitable vaccine access is not merely a matter of ethics—it is a strategic necessity for achieving herd immunity and preventing healthcare system overload.

The concept of universal flu vaccines is also gaining momentum in the scientific community. These vaccines aim to provide long-lasting protection against a broad spectrum of influenza viruses by targeting conserved regions of viral proteins that do not change frequently. While still in clinical trials, early results are promising and could revolutionize how we approach flu prevention in the future. For now, however, annual vaccination remains the best available defense, even if its effectiveness against the new strain is suboptimal.

For high-risk groups—such as healthcare workers, pregnant individuals, the elderly, and those with chronic conditions—getting vaccinated remains critically important. Even partial protection can reduce hospitalizations and fatalities, especially when the virus in question is more virulent or transmissible than usual. Given the current reports of influenza going around in both urban and rural communities, vaccination serves not only as personal protection but also as a communal responsibility.

In the face of uncertainty, vaccination remains one of the most effective tools in our public health arsenal. While not infallible, it offers a level of protection that can significantly alter the course of an outbreak, reducing both individual risk and community spread. Continued research, rapid adaptation, and public engagement will be key to strengthening our defenses against the new flu virus.

New Flu Virus and the Question of Antiviral Resistance

As concerns about the new flu virus grow, so does interest in the therapeutic options available for managing the infection. Antiviral medications, such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), and baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza), have become standard treatments for influenza in both outpatient and hospital settings. These drugs work by inhibiting viral replication, thereby reducing the duration and severity of symptoms when administered early in the course of illness. However, the efficacy of antivirals hinges on the virus’s susceptibility, which is increasingly under threat due to emerging resistance.

Genomic sequencing of the new flu virus has revealed mutations in certain strains that may confer partial resistance to commonly used antivirals. While these mutations are not yet widespread, they signal the potential for reduced treatment efficacy if left unaddressed. Resistance can emerge through natural selection when viruses are exposed to subtherapeutic drug concentrations, or through widespread overuse and inappropriate prescribing of antiviral agents. As such, judicious use of antivirals is more important than ever to preserve their effectiveness.

Clinical guidelines are being updated to reflect the need for early treatment in high-risk populations, as well as the importance of resistance testing in severe or prolonged cases. In instances where resistance is suspected or confirmed, alternative agents or combination therapies may be considered. However, the development of new antiviral compounds has lagged behind that of antibiotics, leaving clinicians with limited options in the face of resistance. Encouraging pharmaceutical innovation and streamlining regulatory pathways will be essential for expanding the antiviral toolkit.

Another promising avenue involves host-directed therapies that enhance the immune response rather than targeting the virus directly. These treatments may include interferons, monoclonal antibodies, or immunomodulators that can be tailored to individual patient profiles. Although still experimental, such approaches offer a way to circumvent viral resistance altogether and provide more robust protection against severe outcomes.

Self-medication and delayed treatment initiation are also contributing to poor outcomes. Many patients wait several days before seeking medical help, often relying on over-the-counter remedies that do little to combat viral replication. Public health campaigns must emphasize the importance of early intervention and guide individuals on when and how to seek professional care. This is especially critical during periods when influenza is going around, and healthcare systems are overwhelmed with flu-related cases.

The emergence of the new flu virus serves as a reminder of the fragile balance between medical innovation and microbial evolution. By using antivirals responsibly, supporting research into new therapeutic options, and improving clinical decision-making, we can better position ourselves to manage this new threat without depleting our pharmacological defenses.

Social Behavior and Environmental Factors Influencing Transmission

One of the less discussed yet highly influential aspects of influenza transmission lies in the social and environmental factors that shape how viruses spread. The new flu virus has demonstrated a capacity to move rapidly through communities, often exploiting social behaviors and living conditions that facilitate close contact and poor ventilation. From school classrooms and office spaces to public transportation and nursing homes, the built environment plays a pivotal role in determining the scale and speed of an outbreak.

Social behavior is a powerful vector for disease propagation. People congregating indoors during colder months, for instance, create ideal conditions for respiratory viruses to thrive. Additionally, behaviors such as inadequate hand hygiene, sharing food or drinks, and failure to isolate while symptomatic all contribute to higher transmission rates. During periods when influenza is going around, these behaviors can accelerate the spread exponentially, especially if the virus is more contagious than typical seasonal strains.

The role of air quality and ventilation has come to the forefront in discussions around respiratory infections. Poorly ventilated spaces allow viral particles to accumulate in the air, increasing the likelihood of inhalation by others. Upgrading HVAC systems, using HEPA filters, and promoting outdoor activities when possible are all strategies that can mitigate this risk. These environmental interventions are particularly important in settings where large groups gather, such as schools, shopping centers, and healthcare facilities.

Occupational exposure is another variable that merits attention. Frontline workers—including those in healthcare, retail, and public transportation—are at heightened risk due to their frequent interactions with the public. Workplace policies that encourage sick leave, stagger shifts, and provide protective equipment can significantly reduce the risk of workplace transmission. Unfortunately, not all employers have the resources or willingness to implement such measures, leading to preventable clusters of infection.

Cultural norms also influence how individuals respond to illness. In some communities, there is a strong ethos of “working through” illness, which discourages people from taking time off unless they are severely incapacitated. This mindset, though rooted in productivity and resilience, becomes dangerous when dealing with a highly transmissible pathogen like the new flu virus. Public health messaging must challenge these norms and reframe illness-related absenteeism as an act of communal responsibility rather than personal weakness.

Environmental justice plays a role as well. Communities with limited access to healthcare, overcrowded housing, and poor sanitation are disproportionately affected during flu outbreaks. Addressing these systemic disparities requires long-term investment and policy reform, but even short-term interventions—such as mobile clinics and subsidized vaccination drives—can make a meaningful difference.

By recognizing the interplay between human behavior, physical spaces, and social dynamics, we can craft more holistic strategies to contain the new flu virus. While vaccines and antivirals are critical, they must be complemented by behavioral and environmental changes that address the root causes of rapid transmission.

Community-Based Strategies to Curb the Spread of the New Flu Virus

As the new flu virus continues to make its presence felt across multiple demographics and regions, the importance of community-level interventions becomes increasingly apparent. While national health directives and global coordination are vital, the true frontline of disease prevention and control resides within communities—local health departments, schools, businesses, and families all play a critical role. A coordinated response rooted in localized knowledge and cultural relevance can effectively slow the spread of the virus and protect the most vulnerable members of society.

Education is foundational to any community health strategy. Accurate, timely, and easily understandable information about the nature of the new flu virus, how it spreads, and how it can be prevented should be disseminated through multiple channels. Local radio, school newsletters, community bulletin boards, and social media are powerful tools when used responsibly. In areas where misinformation is prevalent or health literacy is low, trusted local leaders—such as clergy, teachers, or community health workers—can act as valuable intermediaries, reinforcing evidence-based messages in culturally sensitive ways.

Isolation and quarantine protocols must also be locally adapted to ensure feasibility and compliance. While it is ideal for individuals to remain at home for the full duration of their infectious period, this is not always realistic, particularly in low-income communities where missing work can mean loss of income or job security. Community support systems—such as food delivery programs, financial aid for sick leave, and childcare assistance—can make compliance with public health recommendations more achievable. These measures not only benefit the individual but also reduce the overall viral burden in the community.

Schools represent another focal point for intervention. Children are known to be efficient spreaders of respiratory viruses, and the close-contact nature of classroom environments makes them particularly susceptible to outbreaks. Implementing staggered schedules, promoting outdoor learning, enhancing ventilation, and reinforcing hand hygiene and cough etiquette can make a significant difference. Some school districts have experimented with voluntary flu testing programs and temporary closures during surges, and while these approaches are not without challenges, they offer insights into what might be scalable in a broader context.

Another promising community-level approach is the deployment of mobile health units and pop-up clinics, especially in underserved or rural areas. These units can provide testing, vaccinations, and basic medical care, helping to fill gaps left by overburdened or distant healthcare facilities. They also serve a symbolic role, demonstrating that health authorities are willing to meet people where they are rather than expecting compliance from afar. This model of care delivery has shown success in past public health campaigns and is especially relevant now, as influenza is going around with greater unpredictability and reach.

Finally, partnerships between local governments, non-profits, and private-sector entities can amplify community responses. Whether it’s a local pharmacy offering free flu shots, a business donating masks and sanitizers to a school, or a neighborhood association organizing volunteer outreach, these collaborations create a multiplier effect. They remind us that health is not just the domain of doctors and hospitals but a shared societal responsibility that benefits from diverse forms of participation.

Community resilience is not an abstract concept—it is the sum of practical actions, informed decisions, and mutual support systems. As the new flu virus challenges conventional public health frameworks, communities that adapt with creativity, compassion, and collaboration will be best positioned to weather this and future outbreaks.

Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing During Flu Outbreaks

Often overshadowed by physical health concerns, the psychological impact of flu outbreaks—particularly those involving novel or unusually severe strains—deserves far more attention. The new flu virus, with its unpredictable behavior and widespread media coverage, has understandably heightened public anxiety. For many, especially those who have recently experienced the trauma of COVID-19 or other serious illnesses, this new threat reawakens fears about vulnerability, isolation, and mortality.

Worrying about personal health or the wellbeing of loved ones is a natural response, but when left unchecked, such concerns can evolve into chronic anxiety or health-related obsessive thoughts. This is especially true in the case of a fast-spreading virus that is constantly evolving and for which the scientific understanding is still catching up. The psychological toll is compounded when individuals are bombarded with conflicting messages from different authorities or encounter sensationalist headlines that distort the severity or scope of the threat. While it’s important to stay informed, excessive exposure to distressing news can have the opposite effect, leading to heightened panic rather than productive vigilance.

People with preexisting mental health conditions, such as generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or depression, may find that their symptoms worsen during periods when influenza is going around. This can manifest as excessive handwashing, avoidance of public places, hypervigilance, or in some cases, complete withdrawal from social life. These behaviors, though rooted in a desire for safety, can lead to long-term harm by disrupting routines, relationships, and even immune function due to chronic stress.

Social isolation, whether voluntary or mandated during quarantine, also poses mental health risks. Humans are inherently social creatures, and the absence of regular interaction can lead to feelings of loneliness, despair, and disconnection. This is especially concerning for older adults, individuals living alone, and those in institutional settings like nursing homes or assisted living facilities. Mental health support in these contexts must go beyond crisis hotlines—it should include regular check-ins, creative engagement strategies (such as virtual group activities), and access to professional counseling when needed.

Resilience-building strategies can help mitigate the psychological burden of navigating flu outbreaks. These may include mindfulness practices, structured routines, physical activity, social connection (even if virtual), and reframing one’s sense of control. For instance, focusing on the steps one can take—such as getting vaccinated, wearing masks in crowded places, and staying home when sick—can help counterbalance feelings of helplessness. Mental health professionals can also play a crucial role by integrating public health information into therapy sessions, helping patients contextualize their fears and develop coping mechanisms tailored to their individual needs.

In recognizing the psychological dimension of the new flu virus, we acknowledge that health is holistic. Policies and messaging that include mental wellbeing alongside physical protection are more likely to resonate with the public and foster sustainable, community-wide adherence to safety measures. By treating the mind and body as interdependent, we create a more humane and effective approach to public health.

How the New Flu Virus Is Reshaping Future Public Health Policy

Every significant outbreak leaves its mark not only on individual lives but also on the systems and institutions responsible for safeguarding public health. The new flu virus, with its unique characteristics and widespread impact, is already prompting a reevaluation of how we prepare for, detect, and respond to emerging respiratory threats. Policymakers are being called to revisit outdated assumptions, close known gaps, and build more resilient health systems that can withstand both current and future challenges.

One of the most visible shifts is the renewed emphasis on pandemic preparedness. Governments around the world are recognizing that flu viruses can no longer be considered seasonal nuisances. Rather, they are dynamic, evolving threats capable of disrupting entire societies. As such, funding allocations are being reconsidered, with greater resources directed toward virology research, vaccine development platforms, and stockpiles of antiviral medications and personal protective equipment. Importantly, these investments are being framed not as emergency expenditures but as long-term infrastructure projects essential to national security and economic stability.

Surveillance systems are also undergoing modernization. Traditional methods that rely on manual data collection and delayed reporting are being supplanted by digital platforms that leverage artificial intelligence and real-time analytics. These systems can detect unusual patterns, flag potential outbreaks, and inform targeted interventions more efficiently. Cross-border data sharing, though still hampered by geopolitical tensions, is improving due to the realization that viruses do not respect national boundaries. The concept of a global health information commons—where sequencing data, case reports, and clinical outcomes are pooled and made accessible to researchers worldwide—is gaining traction.

Public health communication is another area ripe for reform. The challenges of the COVID-19 era, followed by confusion around the new flu virus, have exposed the dangers of inconsistent messaging. Future policies must prioritize transparency, scientific accuracy, and the ability to adapt messages as new information emerges. Training spokespeople, coordinating with media outlets, and harnessing the power of social media responsibly are all critical steps in rebuilding public trust.

Healthcare workforce planning is also being reimagined. The burden placed on clinicians, nurses, laboratory technicians, and support staff during viral surges highlights the need for better staffing models, mental health support, and flexible labor policies. Public health education is being integrated into medical and nursing curricula to ensure that future providers are better equipped to respond to outbreaks with both clinical skill and public health awareness.

At the legislative level, there is growing support for policies that link health outcomes to broader social determinants. Housing, food security, education, and employment are increasingly viewed as upstream factors that influence vulnerability to infections like the new flu virus. As such, public health is no longer seen as the sole domain of health departments—it is becoming a cross-cutting concern for every arm of government. The hope is that these systemic insights will not fade once the immediate threat passes but will catalyze a sustained commitment to health equity and resilience.

In many ways, the new flu virus serves as a litmus test for how well we have learned the lessons of past outbreaks. The decisions made today will shape the contours of future health systems, affecting not only how we respond to viruses but how we define the very notion of public health itself.

Frequently Asked Questions: Navigating the Complexities of the New Flu Virus

How does the new flu virus interact with preexisting chronic conditions like diabetes or asthma?

While all flu viruses can pose challenges for individuals with chronic conditions, the new flu virus appears to exacerbate these underlying health issues in more unpredictable ways. People with diabetes, for example, may experience sudden fluctuations in blood glucose levels even before traditional flu symptoms fully emerge. Similarly, individuals with asthma have reported more frequent and severe bronchospasms, potentially requiring emergency intervention. Unlike seasonal flu, which often produces a consistent symptom pattern, the new strain’s erratic behavior can mask worsening comorbidities. This makes proactive monitoring essential—patients with chronic conditions should not only update their vaccinations but also coordinate with their primary care providers on early symptom response plans that include antiviral preauthorization and at-home diagnostic access.

Are there any lifestyle modifications that can specifically reduce the risk of complications from the new flu virus?

Yes, there are several targeted lifestyle changes that can enhance resilience to complications related to the new flu virus, beyond general health advice. Optimizing sleep quality has been linked with improved immune regulation, particularly in modulating inflammatory responses that can escalate flu severity. Nutrition also plays a pivotal role; recent studies highlight the benefit of selenium, zinc, and omega-3-rich diets in mitigating cytokine overproduction—one of the leading causes of flu-related complications. People who engage in regular, moderate-intensity exercise may benefit from enhanced mucosal immunity, which is crucial for defending against respiratory infections. Equally important is managing stress through meditation or cognitive-behavioral techniques, as chronic stress can suppress the immune system’s adaptive responses to novel pathogens like the new flu virus.

What should travelers consider when influenza is going around and new strains are emerging globally?

Travelers should adopt a multifaceted approach to protection, especially during periods when influenza is going around and the spread of the new flu virus is confirmed in multiple regions. This includes checking local flu activity maps maintained by health organizations and adjusting itineraries accordingly if surges are reported in destination areas. For air travel, upgraded precautions—such as wearing N95 masks and selecting window seats to minimize exposure—can make a significant difference. Travelers should also carry a personal medical kit containing antiviral medications (with a doctor’s prescription), rapid test kits, and supplemental electrolytes to stay hydrated during illness. It’s advisable to pre-identify medical facilities in the destination country, particularly those with English-speaking staff and flu treatment capabilities, in case medical attention becomes necessary.

How does the new flu virus affect pediatric patients differently than adults?

Emerging case studies suggest that children infected with the new flu virus may not always display the classic symptoms such as high fever or pronounced fatigue seen in adults. Instead, pediatric cases often present with gastrointestinal symptoms—nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—which can be easily mistaken for unrelated conditions like food poisoning or viral gastroenteritis. Neurological symptoms, including transient disorientation or behavioral changes, have also been documented in children, potentially due to different blood-brain barrier permeability at younger ages. Because children often serve as super-spreaders in community settings, early detection is vital, even if symptoms appear mild. Pediatricians now recommend a lower threshold for testing and isolation when children exhibit flu-like signs during seasons when influenza is going around or when new strains are being tracked by local health authorities.

Can air filtration systems reduce the risk of household transmission of the new flu virus?

Yes, high-efficiency air filtration systems—particularly those using HEPA or UV-C light technology—can significantly reduce viral particles in indoor spaces and thus lower the risk of intra-household transmission of the new flu virus. These systems are especially effective in homes where one member is symptomatic or recovering from infection. The placement of portable filters in shared areas like kitchens and living rooms can localize air purification and prevent aerosol buildup. Coupled with strategic ventilation practices such as opening windows for cross-breezes, these technologies offer a layer of environmental defense. As influenza is going around more persistently in densely populated areas, investing in home air quality upgrades has become a practical component of modern flu prevention.

What innovations in vaccine delivery are being explored for future outbreaks of the new flu virus?

Several exciting innovations are in development to improve the speed, accessibility, and adaptability of flu vaccinations, especially as the world grapples with the new flu virus and its evolving subtypes. Needle-free delivery methods, such as intradermal patches with microarray technology, are being tested to reduce pain and increase vaccination rates among needle-averse populations. mRNA-based flu vaccines are another breakthrough, offering faster production timelines and greater adaptability to rapidly mutating viruses. Research is also advancing toward a pan-influenza vaccine that targets conserved viral regions, potentially rendering annual flu shots obsolete. These technological advances not only address immediate needs during surges of influenza going around but also represent a paradigm shift in long-term public health preparedness.

What should caregivers do differently when caring for someone infected with the new flu virus at home?

Caring for a flu-infected individual at home has always required caution, but the new flu virus introduces additional complexities that caregivers must consider. First, the caregiving space should ideally be isolated, with separate bathroom facilities if possible, and equipped with an air purifier. Caregivers should wear a high-grade mask (preferably N95) and gloves when in direct contact with the patient and dispose of or sanitize them properly after each use. Nutritional support is also crucial—providing nutrient-dense, easy-to-digest meals can bolster recovery and minimize inflammation. Additionally, caregivers should monitor vital signs twice daily using pulse oximeters and digital thermometers, keeping an eye out for sudden shifts that might indicate complications such as secondary pneumonia. This is particularly important during times when influenza is going around and healthcare systems are strained, as timely escalation can save lives.

How might climate change influence the patterns of future flu outbreaks, including those caused by the new flu virus?

Climate change is expected to significantly reshape the dynamics of flu seasonality and virus evolution, including the emergence and behavior of strains like the new flu virus. Warmer winters may lead to milder but longer-lasting flu seasons, blurring the traditional boundaries between high and low transmission periods. Changes in precipitation and humidity can also alter the survivability of airborne viruses and the behavior of vector species, making outbreaks harder to predict. Additionally, climate-driven migration and urbanization will increase population density in certain regions, creating fertile grounds for rapid viral transmission. Monitoring these environmental variables will become essential in forecasting when and where influenza is going around, thereby informing vaccine distribution, public health campaigns, and international travel guidelines.

How can small businesses and employers support flu prevention during seasons dominated by the new flu virus?

Small businesses and employers play a crucial role in community health resilience, especially when the new flu virus contributes to a more aggressive flu season. Offering paid sick leave reduces the pressure on employees to work while symptomatic, thereby minimizing workplace transmission. Employers can also facilitate on-site vaccination clinics in partnership with local health departments or pharmacies, making it easier for staff to stay protected. Beyond medical interventions, simple environmental changes—such as improving ventilation, rotating shifts, and supplying hand sanitizer—can dramatically reduce the risk of outbreaks. Transparent communication is equally important; sharing updates when influenza is going around and encouraging staff to report symptoms without stigma fosters a culture of health awareness. Employers who model responsible behavior—such as staying home when sick—help normalize best practices across all levels of their organization.

What are the long-term public health lessons we can draw from managing the new flu virus?

Managing the new flu virus has offered invaluable insights into the gaps and strengths of our current public health infrastructure. One of the clearest lessons is the need for rapid genomic surveillance systems that can detect mutations in real time and forecast future outbreaks. Public health education must also evolve, becoming more participatory and culturally relevant so that communities can act not merely as recipients of guidelines but as partners in disease prevention. Another critical takeaway is the importance of integrated mental health services, which should be built into flu response frameworks from the outset rather than treated as secondary concerns. On a policy level, the experience has reinforced the value of intersectoral collaboration—health, education, housing, and labor policies must align when influenza is going around to create an environment that supports public well-being holistically. Ultimately, these lessons can fortify our global health systems against not only future flu strains but also other emerging infectious threats.

Conclusion: Protecting Yourself and Your Community from the New Flu Virus

As we have seen, the emergence of the new flu virus is more than just a seasonal health concern—it is a multifaceted challenge that touches on science, society, behavior, and policy. From its atypical symptoms and heightened transmissibility to its potential for antiviral resistance and mental health impacts, this novel strain demands a comprehensive, informed response. Staying protected in the face of such a threat requires both personal vigilance and collective action.

Understanding that influenza is going around is only the beginning. The true value lies in what we do with that information—how we adjust our behaviors, support our communities, and hold our systems accountable. Vaccination, early testing, and antiviral treatment remain cornerstones of prevention and care, but they must be supported by strong communication, equitable access, and coordinated public health strategies. Addressing environmental and social factors, investing in healthcare infrastructure, and emphasizing mental wellbeing all contribute to a more resilient society capable of withstanding future health crises.

Crucially, the lessons we learn from this outbreak will inform how we prepare for others. Every public health challenge presents an opportunity—not only to defend against a present danger but to build a more robust and compassionate framework for the future. In that spirit, staying informed about the new flu virus is not just a personal responsibility but a civic one. Our actions—individually and collectively—can shape the trajectory of this virus and determine how its story unfolds in the years to come.

Let this serve as a call to awareness, empathy, and engagement. The flu may be familiar, but each new strain reminds us that complacency is not an option. By arming ourselves with knowledge and acting with intention, we can protect not only our own health but also the wellbeing of those around us. In a world increasingly defined by global interdependence, there is perhaps no greater act of care than choosing to be prepared.

Further Reading:

The world should prepare now for a potential H5N1 flu pandemic, experts warn