Why Micronutrient Deficiency Is a Global Health Concern

Micronutrient deficiency, often referred to as “hidden hunger,” is a widespread yet under-recognized issue that affects billions of people across the globe. Unlike traditional malnutrition, which is often visible through stunted growth or wasting, micronutrient deficiencies can remain invisible for months or years, silently undermining health. These deficiencies are not restricted to low-income countries or areas of famine; they are increasingly prevalent even in high-income countries where food is abundant but not necessarily nutritious. Individuals may consume sufficient calories and still experience poor health due to diets lacking essential vitamins and minerals. This disconnect between food quantity and quality underscores why micronutrient deficiency deserves serious attention.

In particular, the growing global burden of noncommunicable diseases has pushed public health experts to reexamine the role of nutrition in disease prevention. The lack of key nutrients can impair the immune system, slow cognitive development, reduce work productivity, and increase susceptibility to infections and chronic illness. For instance, vitamin A deficiency compromises vision and immunity, while iron deficiency leads to anemia and chronic fatigue. Understanding these risks is essential not just for healthcare providers and policymakers but also for individuals seeking to take greater control over their long-term health.

You may also like: Macronutrients vs Micronutrients: What the Simple Definition of Macronutrients Reveals About Your Diet and Health

Defining Micronutrient Deficiency and Its Impact on Human Health

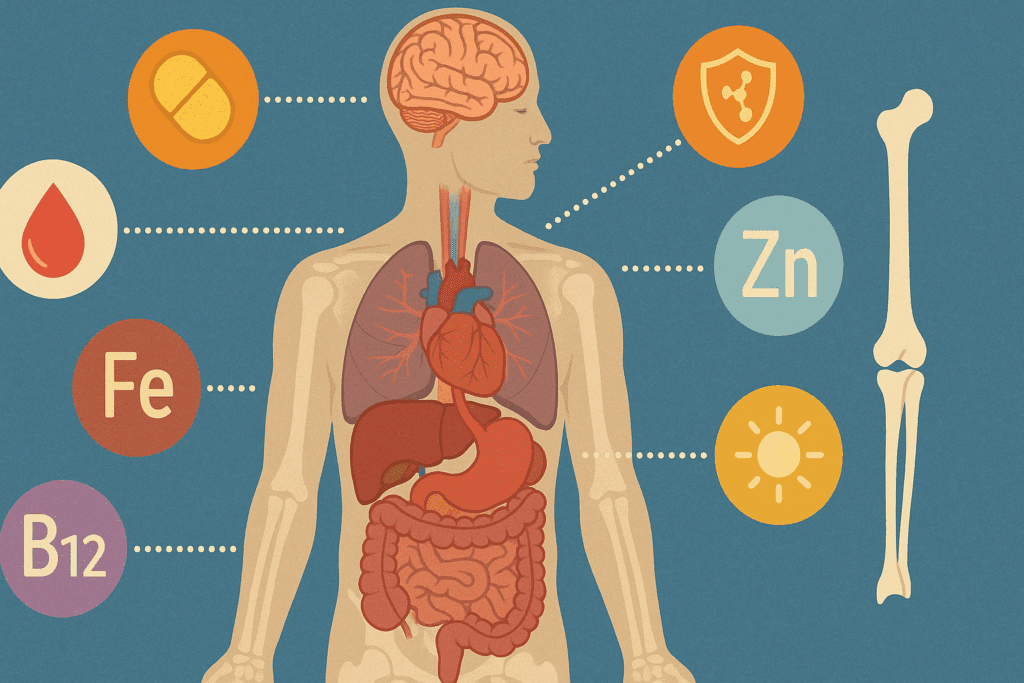

Micronutrients are nutrients required in minute amounts but are critical for proper growth, development, and physiological function. These include vitamins such as A, B-complex, C, D, E, and K, and minerals like iron, zinc, calcium, magnesium, iodine, and selenium. A micronutrient deficiency arises when the body does not receive or absorb adequate levels of these nutrients, which can disrupt essential biological processes.

Iron deficiency, the most common worldwide, reduces the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity and is a leading cause of anemia. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with bone demineralization, autoimmune conditions, and increased vulnerability to respiratory infections. In children, iodine deficiency can impair cognitive development and lower IQ. These are just a few examples of how vital micronutrients are to fundamental bodily functions.

Vitamin deficiencies linked to malnutrition can have severe effects on both physical and mental health. For example, folate and vitamin B12 are essential for DNA synthesis and neurological function. Deficiencies in these can lead to developmental delays in children and cognitive decline in adults. Chronic deficiencies also contribute to long-term illnesses like cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and metabolic disorders. These health burdens make early detection and prevention a priority in public health strategies globally.

How Malnutrition and Vitamin Deficiencies Are Interconnected

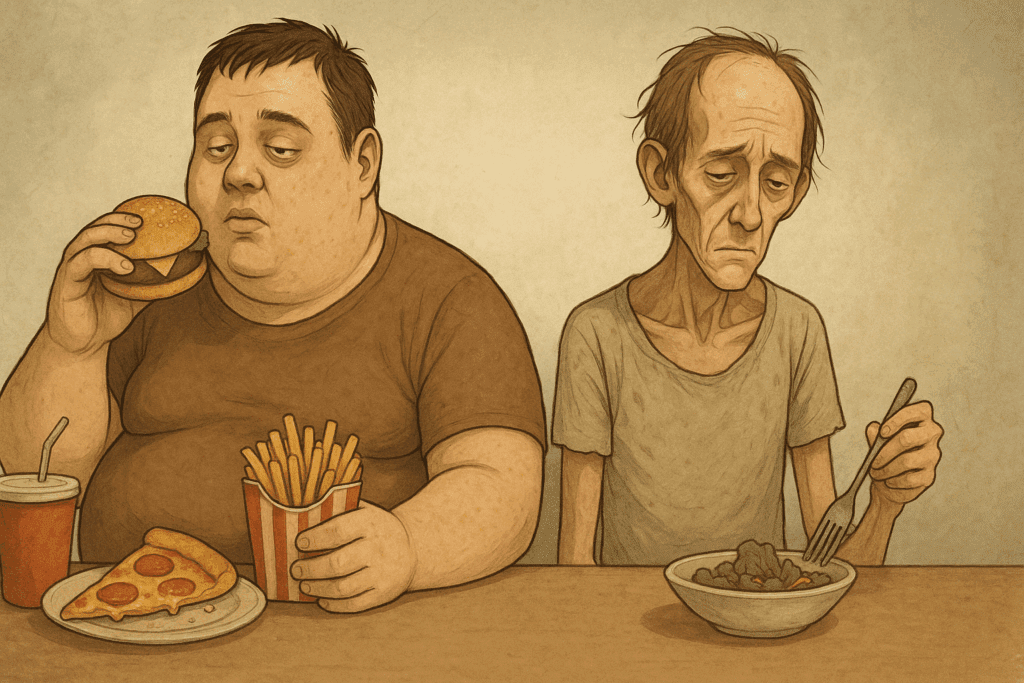

Malnutrition is a multifaceted condition that refers to both undernutrition and overnutrition. A person may consume an excess of calories yet remain deficient in critical nutrients—a phenomenon increasingly common in industrialized nations due to highly processed, nutrient-poor diets. Thus, vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition can occur even when food is plentiful, especially when it lacks variety and nutrient density.

The interrelationship between micronutrient deficiency and malnutrition is particularly evident in vulnerable populations. Pregnant women, infants, the elderly, and individuals with chronic illnesses are especially at risk. Poor maternal nutrition can lead to low birth weights and developmental abnormalities in newborns. In young children, deficiencies in iron, zinc, and vitamin A can result in growth retardation, increased risk of infections, and long-term cognitive deficits. The implications go beyond immediate health, affecting economic productivity and educational attainment across entire populations.

It is also worth noting that malnutrition does not always stem from poverty alone. Cultural dietary practices, restricted eating patterns, and poor health literacy contribute significantly to inadequate nutrient intake. Thus, prevention must involve not just food security but education, behavioral change, and policy reform to encourage better eating habits.

Micronutrient Deficiency in High-Income Countries: The Hidden Threat

Contrary to popular belief, micronutrient deficiency is not confined to underdeveloped or low-income countries. In Western nations, many individuals subsist on diets high in sugar, refined carbohydrates, and unhealthy fats but low in essential vitamins and minerals. This modern dietary pattern contributes to “hidden hunger,” where people may feel full but remain undernourished.

Common deficiencies in affluent societies include vitamin D, B12, magnesium, and potassium. These can arise from limited sun exposure, poor gut health, medications that impair absorption, and monotonous food choices. For example, vitamin D deficiency is prevalent among individuals who spend most of their time indoors, while B12 deficiency is more common in older adults and vegans.

One of the most insidious aspects of this trend is the normalization of poor diet quality. Fast food, convenience meals, and sweetened beverages dominate the average diet in many regions, crowding out whole foods that provide essential nutrients. Public health messaging must therefore shift focus from mere calorie counting to improving nutrient density and overall dietary quality.

Clinical Consequences of Vitamin Deficiencies Due to Malnutrition

The long-term consequences of vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition are medically significant and far-reaching. For instance, vitamin A deficiency is a leading cause of preventable blindness in children. Zinc deficiency impairs immune responses and delays wound healing. Lack of vitamin C can lead to scurvy, a disease characterized by bleeding gums, anemia, and joint pain.

In adults, chronic micronutrient deficiencies contribute to degenerative diseases. Calcium and vitamin D deficiencies are associated with osteoporosis and bone fractures, especially among postmenopausal women and the elderly. Low levels of B vitamins have been linked to depression, fatigue, memory problems, and elevated homocysteine levels, a risk factor for heart disease.

Another overlooked aspect is the mental health component of micronutrient deficiencies. Emerging research links inadequate intake of magnesium, omega-3 fatty acids, and certain B vitamins to anxiety, depression, and even neurodevelopmental disorders in children. These findings emphasize the need for nutritional assessment as part of routine mental health care.

Evidence-Based Strategies to Prevent Micronutrient Deficiency

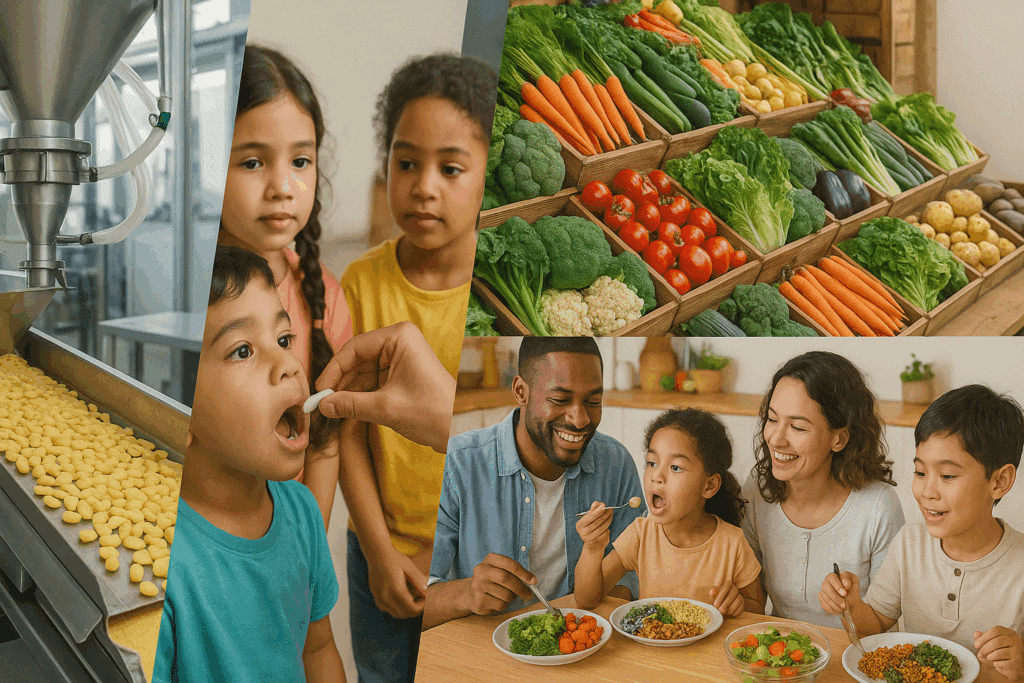

Effective prevention of micronutrient deficiency and vitamin deficiencies linked to malnutrition involves a comprehensive strategy that includes food fortification, dietary diversification, supplementation, and public education. Food fortification is among the most cost-effective public health interventions. The addition of iodine to salt, folic acid to flour, and vitamin D to milk has significantly reduced the prevalence of related deficiencies in many countries.

Supplementation programs also play a vital role, especially in high-risk groups. Prenatal vitamins containing folate and iron are standard in many healthcare systems to prevent birth defects and maternal anemia. In regions where vitamin A deficiency is endemic, the WHO recommends high-dose supplementation for children under five.

Dietary diversity remains the gold standard for preventing deficiencies. A balanced intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, lean proteins, and dairy provides a broad spectrum of micronutrients in bioavailable forms. For example, pairing iron-rich foods with vitamin C sources enhances absorption, while fermented foods support gut health and nutrient uptake.

The Role of Healthcare, Policy, and Community Initiatives

Healthcare providers have a central role in identifying and managing micronutrient deficiencies. Routine screening for iron status, vitamin D levels, or B12 deficiency should be incorporated into preventive care, especially for at-risk populations. Integrating nutrition education into medical training is critical for equipping providers with the knowledge needed to guide patients toward healthier choices.

On the policy front, governments must enact measures that support food accessibility, regulate misleading food advertising, and subsidize nutritious options. Community-based programs can bridge gaps by providing nutrition education, distributing supplements, and improving local food environments. Schools, workplaces, and public institutions should all be leveraged as platforms for nutritional outreach.

Equity is a central theme in these efforts. Micronutrient interventions must be tailored to cultural preferences, socioeconomic constraints, and regional dietary patterns. A one-size-fits-all approach risks missing the mark. Engaging local leaders, community health workers, and educators ensures that solutions are not only evidence-based but also relevant and sustainable.

Environmental and Societal Dimensions of Nutrient Access

The growing challenge of climate change adds another layer to the issue of nutrient availability. Rising carbon dioxide levels may reduce the nutritional content of crops, making it harder to meet daily micronutrient requirements even with adequate food intake. This phenomenon could disproportionately affect regions already struggling with vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition.

Moreover, urbanization and the decline of traditional farming practices have distanced communities from nutrient-rich, homegrown foods. As people become more reliant on supermarkets and processed goods, they lose access to seasonal, local produce that once formed the backbone of a nutrient-dense diet.

Efforts to restore these systems—such as supporting community gardens, urban agriculture, and farmers’ markets—can help reintroduce fresh, unprocessed foods into everyday diets. Investing in sustainable agriculture also supports environmental resilience and food security, both crucial for long-term public health.

Mental Health, Micronutrients, and Whole-Person Wellness

Mental wellness is increasingly viewed through a nutritional lens. While therapy and medication remain cornerstones of treatment, dietary interventions are gaining ground as adjunct therapies. Nutrients like magnesium, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids play roles in neurotransmitter function, inflammation regulation, and stress resilience.

Clinical studies suggest that micronutrient supplementation may alleviate symptoms in some individuals with depression, anxiety, or ADHD. While more research is needed, the growing body of evidence supports the integration of dietary assessments into mental health care. Nutritionists, psychologists, and primary care providers must work collaboratively to ensure that emotional and physical health are addressed in tandem.

Whole-person wellness—an approach that considers physical, mental, and emotional dimensions of health—requires attention to nutrition as a foundational element. Encouraging healthy eating habits is therefore not just about preventing disease but about enhancing quality of life.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Micronutrient Deficiency and Vitamin Deficiencies Linked to Malnutrition

1. Can someone be overweight and still suffer from a micronutrient deficiency?

Absolutely. In fact, individuals who are overweight or obese may be at higher risk for certain forms of micronutrient deficiency. This is because excess calorie consumption from processed foods often lacks essential vitamins and minerals. For example, diets high in refined carbohydrates, sugars, and saturated fats tend to displace nutrient-dense options like leafy greens, legumes, and fish. People may assume that obesity rules out malnutrition, but in reality, vitamin deficiencies linked to malnutrition often coexist with overnutrition. Addressing this paradox requires both reducing excess calories and improving diet quality through whole-food, nutrient-rich options.

2. How does chronic stress affect the risk of micronutrient deficiency?

Chronic stress can significantly increase the body’s demand for certain micronutrients, particularly B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, and vitamin C. Prolonged stress elevates cortisol, which may interfere with nutrient absorption and metabolism. Additionally, stress can lead to changes in appetite, gut health, and dietary choices, often resulting in reduced intake of nutrient-dense foods. Over time, this creates a feedback loop where stress contributes to micronutrient deficiency, and that deficiency, in turn, exacerbates mental and physical stress responses. Therefore, managing stress is not just about psychological well-being but also about protecting nutritional status.

3. Are there new technologies that help detect vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition earlier?

Yes, advances in nutritional science have led to more precise diagnostic tools for early detection of vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition. Technologies like metabolomic profiling, dried blood spot testing, and hair mineral analysis allow for comprehensive micronutrient assessment with minimal invasiveness. Some personalized nutrition platforms now integrate artificial intelligence to analyze diet, genetics, and biomarkers to predict and prevent nutrient shortfalls. These innovations are especially useful in preventive care, helping healthcare providers intervene before symptoms manifest. As these tools become more affordable and widely available, early screening could become a standard part of routine health checks.

4. What are the long-term economic impacts of widespread micronutrient deficiency?

The economic implications of micronutrient deficiency are substantial and far-reaching. Individuals with chronic deficiencies often face increased healthcare costs due to higher susceptibility to infections, fatigue-related productivity loss, and the progression of preventable diseases. For example, iron deficiency anemia in the workforce has been linked to reduced job performance and earnings. At a societal level, governments face rising healthcare expenditures and lost economic output due to impaired cognitive development in children, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Investing in prevention programs for vitamin deficiencies caused by malnutrition is not only a public health priority but also a sound economic strategy.

5. How do digestive disorders contribute to vitamin deficiencies caused by malnutrition?

Digestive conditions such as Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and chronic gastritis can impair nutrient absorption, leading to vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition even when dietary intake appears sufficient. These disorders often damage the intestinal lining or alter enzyme production, limiting the body’s ability to absorb vitamins like B12, D, and folate. In some cases, inflammation or surgical resections can drastically reduce absorption surface area, exacerbating deficiencies. Individuals with these conditions often require supplementation, but the form and route (oral vs. injectable) must be tailored to their specific needs. Proactive nutritional monitoring is essential in managing the long-term health of patients with gastrointestinal diseases.

6. How can workplaces help prevent micronutrient deficiency among employees?

Employers have a unique opportunity to support employee well-being by promoting nutritional health in the workplace. Providing access to nutrient-rich meals in cafeterias, offering educational workshops on diet, and making healthy snacks readily available can all reduce the risk of micronutrient deficiency among workers. Some companies even incorporate on-site nutritional counseling or provide wellness stipends that can be used for supplements or meal planning services. In physically demanding jobs or high-stress environments, such interventions are particularly impactful. Encouraging better nutrition isn’t just good for employees—it also enhances productivity, reduces absenteeism, and fosters a healthier work culture.

7. Are certain populations more biologically prone to vitamin deficiencies linked to malnutrition?

Yes, genetic and physiological factors can predispose certain individuals to vitamin deficiencies malnutrition. For example, genetic mutations affecting folate metabolism or vitamin D receptor sensitivity may increase nutrient needs. Similarly, older adults often experience reduced stomach acid production, which impairs B12 absorption. Pregnant women, infants, and people with darker skin (who synthesize less vitamin D from sunlight) also face heightened risk. Recognizing these biological vulnerabilities allows for more personalized and effective preventive care, including targeted supplementation and dietary recommendations.

8. Can environmental pollutants influence micronutrient status?

Emerging research suggests that environmental toxins like lead, cadmium, and mercury can interfere with the body’s ability to absorb or utilize essential nutrients. For example, lead competes with calcium in metabolic processes, while mercury may deplete selenium levels. Individuals exposed to high levels of pollution may require additional dietary or supplemental support to counteract these effects. Moreover, soil degradation from industrial agriculture has reduced the micronutrient content of many crops, contributing indirectly to micronutrient deficiency through the food supply. Environmental health, therefore, intersects closely with nutritional resilience.

9. How might digital tools support the fight against vitamin deficiencies caused by malnutrition?

Digital health platforms can play a transformative role in addressing vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition. Mobile apps now allow users to log food intake, track micronutrient consumption, and receive tailored alerts when intake falls below recommended levels. Wearables integrated with biosensors can provide real-time feedback on hydration, activity, and even nutrient status. Additionally, machine learning algorithms can analyze large datasets to predict nutrient trends at the population level, enabling earlier interventions. These technologies empower individuals to take a more active role in their nutrition while giving public health officials valuable insights for planning interventions.

10. What are some overlooked signs of micronutrient deficiency that people often miss?

Many early signs of micronutrient deficiency are subtle and easily attributed to stress, aging, or lifestyle factors. Chronic fatigue, irritability, hair thinning, frequent infections, and poor wound healing may all indicate underlying nutrient insufficiencies. Cracks at the corners of the mouth, brittle nails, or a pale tongue can signal deficiencies in B vitamins, iron, or zinc. Because these symptoms are non-specific, they often go unaddressed until more serious health issues arise. Increased public awareness and routine screening are essential for catching these early warning signs before they escalate into more serious health concerns.

Conclusion: Combating Micronutrient Deficiency and Malnutrition with Knowledge, Nutrition, and Policy

Micronutrient deficiency and vitamin deficiencies due to malnutrition are global health threats that demand immediate and sustained attention. These conditions quietly impair development, weaken immune defenses, and set the stage for chronic disease. They are not confined to the visibly malnourished but are increasingly present in populations consuming enough—if not too many—calories.

The solutions are multi-layered: fortifying staple foods, expanding supplementation programs, and fostering dietary diversity through education and accessibility. Equally important are systemic changes in healthcare, policy, and food systems to ensure that everyone, regardless of background, has the opportunity to achieve nutritional adequacy.

Preventing micronutrient deficiency begins with awareness and is sustained through action—at individual, community, and governmental levels. By investing in nutrition as a cornerstone of public health, we not only prevent disease but also promote vitality, resilience, and equity. As we continue to uncover the intricate relationships between diet and health, addressing vitamin deficiencies linked to malnutrition will remain a foundational step toward a healthier world.

Further Reading:

Micronutrient malnutrition across the life course, sarcopenia and frailty